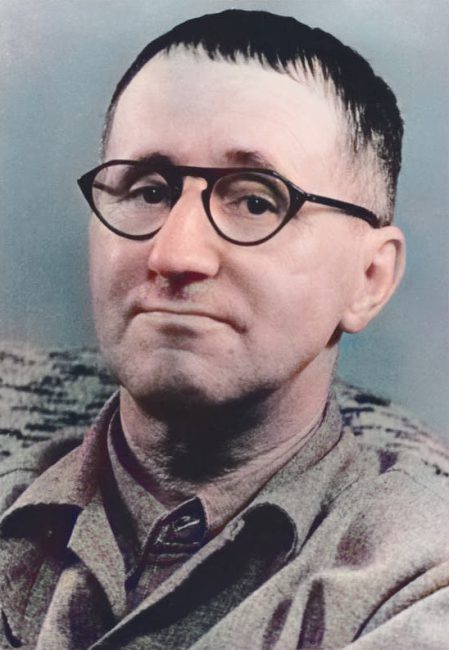

Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956)

On February 10, 1898, German poet, playwright, theatre director, and Marxist Bertolt Brecht was born. A theatre practitioner of the 20th century, Brecht is best known for his contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production. There are few areas of modern theatrical culture that have not felt the impact or influence of Brecht’s ideas and practices.

“It is not enough to demand insight and informative images of reality from the theater. Our theater must stimulate a desire for understanding, a delight in changing reality.”

— Bertolt Brecht, Essays on the Art of Theatre (1954)

Bertolt Brecht, Germany, and the Radio Theory

I’m from Germany. Thus, it is somehow self-evident that Bertolt Brecht was one of the main subjects of my German lessons back in high school. Maybe this is also the reason why I don’t really enjoy reading his writings and his dramas. Things haven’t changed much, at least if it concerns Bertolt Brecht. In the last decade, Brecht was often cited for his radio theory, and that with the Web as we know it by today with its blogs, microblogs and wikis, has become the materialization of what Brecht had demanded originally in his radio theory. In fact, he had demanded a kind of radio, where everybody had the possibility to broadcast by himself. A radio where there are not only big broadcasting companies at work, but where the medium has something like a reverse channel, where the recipient has the chance to become broadcaster himself. Well, the Web in fact is something like Brecht had originally demanded. Nevertheless, I don’t appreciate his writings, although some of his poetry – yes, he also wrote poetry – is really excellent and rather touching. But, let’s take a look on the life and work of Bertolt Brecht, poet, playwright, and convinced Marxist.

Youth and World War I

Bertolt Brecht was born in Augsburg, Bavaria , to a devout Protestant mother and a Catholic father, who worked for a paper mill into a comfortable middle class life. Thanks to his mother’s influence, Brecht knew the Bible, a familiarity that would have a lifelong effect on his writing. On the outbreak of the First World War broke out, Brecht initially was very enthusiastic, but soon changed his mind on seeing his classmates “swallowed by the army”. Thanks to an additional medical course at Munich University, where he enrolled in 1917, he had found a loop hole not to get right away drafted to the front. While in 1916, Brecht’s newspaper articles began appearing under the new name “Bert Brecht”, he was drafted into military service in the autumn of 1918, but fortunately for him the war ended already a month later.

Drums in the Night

In 1921, Brecht took a small part in the political cabaret of the Munich comedian Karl Valentin, whom Brecht compared to Chaplin for his “virtually complete rejection of mimicry and cheap psychology“. In the very same year, Brecht took a trip to Berlin and attended the rehearsals of Max Reinhardt, Erwin Piscator, and other major directors. In 1922, his play Drums in the Night opened in Munich at the Kammerspiele and later at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin. He received the prestigious Kleist prize for young dramatists as a result. In 1923, his two plays Jungle of Cities and Baal were performed. After moving to Berlin in 1924, he met a communist Viennese actress, Helene Weigel, whom he married after the divorce from his first wife Marianne Zoff in 1929. Dadaist Georg Grosz, who knew him during this time, described Brecht in the following way:

“Brecht was interested in English writers and Chinese philosophers. He read Swift, Butler and Wells, and also Kipling. He dressed like nobody else in the circle, and looked like some kind of engineer or car mechanic, always wearing a thin leather tie – without oil stains, of course. Instead of the usual sort of waistcoat, he wore one with long sleeves; the cut of all his suits were baggy and somewhat American, with padded shoulders and wedge-shaped trousers. Without his monkish face and the hair combed down on his forehead he might have been mistaken for a cross between a German chauffeur and a Russian commissar.”

The Threepenny Opera

In 1927 Brecht collaborated with the composer Kurt Weill to produce the musical play, The Little Mahagonny, followed by The Threepenny Opera. Although based on The Beggar’s Opera that was originally produced in 1728, Brecht added his own lyrics that illustrated his growing belief in Marxism. The “play with music in a prelude and eight pictures” became the most successful German theater performance until 1933, some musical numbers like the Moritat by Mackie Messer (‘Mack the Knife‘) became world hits.

Brecht’s Theory of Epic Theatre

Brecht attempted to develop a new approach to the the theatre, his so-called “Epic Theatre“. He tried to persuade his audiences to see the stage as a stage, actors as actors and not the traditional make-believe of the theatre. Brecht required detachment, not passion, from the observing audience. The purpose of the play was to awaken the spectators’ minds so that he could communicate his version of the truth. In 1933 Brecht went into exile, first in Scandinavia (1933-41), and then in the United States (1941-47), where he also did some film work in Hollywood. In Germany his books were burned and his citizenship was withdrawn. Although being cut off from the German theatre, he wrote most of his great plays, his major theoretical essays and dialogues, and many of his poems. Notable among his play are Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder (1941; Mother Courage and Her Children), a chronicle play of the Thirty Years’ War; Leben des Galilei (1943; The Life of Galileo); Der gute Mensch von Sezuan (1943; The Good Woman of Setzuan), a parable play set in prewar China; Der Aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (1957; The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui), a parable play of Hitler’s rise to power set in prewar Chicago; Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti (1948; Herr Puntila and His Man Matti), a popular play about a Finnish farmer who oscillates between churlish sobriety and drunken good humour; and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (first produced in English, 1948; Der kaukasische Kreidekreis, 1949), the story of a struggle for possession of a child between its highborn mother, who deserts it, and the servant girl who looks after it.

Hollywood never opened its Doors

But Hollywood never opened its doors to Brecht, who sketched notes for more than fifty films.. Brecht drew the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Although he managed to deflect accusations of being a Communist, he moved to Switzerland after the hearings. He relocated to East Berlin in 1949 and ran the Berliner Ensemble, a theater company. As a director, he advocated the “alienation effect” in acting — an approach intended to keep the audience emotionally uninvolved in the plights of the characters. In the West as well as in the East Germany Brecht became the most popular contemporary poet, outdistanced only by such classics as Shakespeare, Schiller, and Goethe. In 1955 Brecht received the Stalin Peace Prize. His acceptance speech, delivered in Moscow, was translated into Russian by Boris Pasternak. The next year he contracted a lung inflammation and died of a coronary thrombosis on August 14, 1956, in East Berlin.

Bertolt Brecht and Epic Theater: Crash Course Theater #44, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Bertolt Brecht biography at Gradesavers

- [2] Bertolt Brecht biography at Spartacus Educational

- [3] Bertolt Brecht biography at Brandeis University

- [4] Bertolt Brecht on IMDb

- [5] Brecht’s works in English: A bibliography

- [6] Works by or about Bertolt Brecht at Internet Archive

- [7] Bertolt Brecht at Wikidata

- [8] Bertolt Brecht and Epic Theater: Crash Course Theater #44, Crash Course @ youtube

- [9] Newspaper clippings about Bertolt Brecht in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [10] “International Brecht Society – Brecht Chronology”

- [11] Timeline for Bertolt Brecht, via Wikidata

,_1913.jpg?width=300)

.jpg?width=300)

.jpg?width=300)