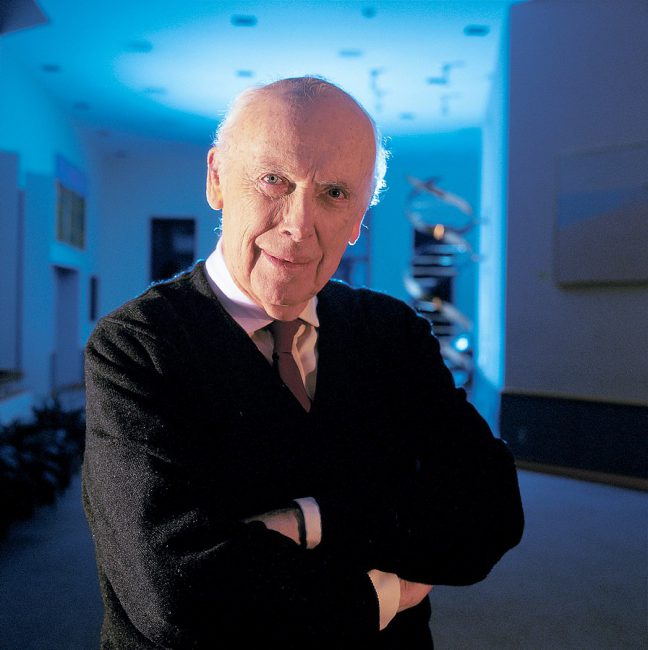

James D. Watson (*April 6, 1928)

On February 28, 1953, American molecular biologist James D. Watson and English biophysicist Francis Crick announced to friends that they succeeded to determine the chemical structure of DNA.

“When finally interpreted, the genetic messages encoded within our DNA molecules will provide the ultimate answers to the chemical underpinnings of human existence.”

– James D. Watson, in [11]

DNA and RNA – the Prelude

In 1869, the Swiss physician Friedrich Miescher discovered a substance obtained by mild acid treatment from the nuclei of leukocytes in an extract of pus, which he called nucleus. Miescher worked in Felix Hoppe-Seyler‘s laboratory in Tübingen Castle In 1889 the German Richard Altmann isolated proteins and nucleic acid from the nucleus. In 1896 the German Albrecht Kossel discovered the four bases A, C, T and G in nucleic acid. In 1919, Phoebus Levene identified the components of the DNA (base, sugar and phosphate residue). Levene proposed a chain-like structure of the DNA in which the nucleotides are joined together by the phosphate residues and are constantly repeated. As early as 1932, K. Voit and Hartwig Kuhlenbeck (1897-1984) regarded DNA as an effective component of chromosomes and nuclear chromatin respectively. In 1937, William Astbury published X-ray diffraction patterns for the first time, which pointed to a repetitive structure of DNA.

The term ‘nucleic acid’ was then coined by Richard Altmann and it was only found in the chromosomes. The Lithuanian-American biochemist Phoebus Levene at Rockefeller Institute made further achievements concerning the DNA’s structure, showing that its components, the sugar and phosphate chain were linked in the order phosphate-sugar-base. Each of these was named nucleotide and the scientist assumed that the DNA molecule consisted of a string of nucleotide units, which were linked together through phosphate groups. In his understanding however, the chain was short and its bases repeated in a fixed order, the theory that the DNA was a polymer was later suggested by Torbjorn Caspersson and Einar Hammersten.

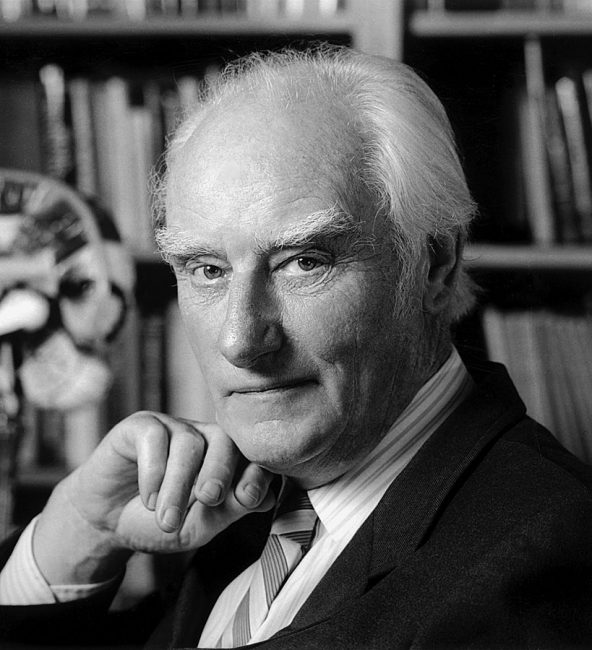

Francis Crick (1916 – 2004)

Franklin, Wilkins, Crick, and Watson

Further efforts on the DNA’s structure were made in the 1950’s, and three known groups worked on the topic. Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins [6] of King’s College London belonged to the first group, Francis Crick and James Watson from Cambridge formed the second group and Linus Pauling and his team at Caltech depicted the third. Crick and Watson were able to build physical models of metal rods and balls, incorporating the chemical structured of the nucleotides. In the late 1940’s, Pauling and his team discovered many proteins included helical shapes and also Wilkins found out that in the DNA’s structure, helix’ were somehow involved. Watson and Crick then began answering questions like whether the bases pointed toward the helical axis or away or what the angles and coordinated of all atoms and bonds were.

Watson came to England in 1951 after completing his doctorate a year earlier at Indiana University Bloomington in the USA. Although he had received a scholarship for molecular biology, he was increasingly concerned with the question of the human genome. Crick was unsuccessfully doing his doctorate in Cambridge on the crystal structure of the hemoglobin molecule when he met Watson in 1951. At that time, a fierce race for the structure of DNA had already broken out, in which Linus Pauling of the California Institute of Technology was one of the participants. Watson and Crick had actually been assigned to other projects and had no significant expertise in chemistry. They based their considerations on the research results of the other scientists.

The Discovery

Watson said he wanted to decode the genome without having to learn chemistry. In a conversation with the renowned chemist and creator of the Chargaff rules, Erwin Chargaff, Crick forgot important molecular structures, and Watson made inappropriate remarks in the same conversation that revealed his ignorance in the field of chemistry. Chargaff then called the young colleagues “scientific clowns”. Watson visited Maurice Wilkins at King’s College in London in late 1952, where he was shown DNA x-rays of Rosalind Franklin (against Franklin’s will). Watson immediately saw that the molecule had to be a double helix; Franklin himself had suspected the presence of a helix based on the data, but had no convincing model for the structure. Since it was known that the purine and pyrimidine bases form pairs, Watson and Crick succeeded in deriving the entire molecular structure. At the Cavendish Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, they developed the double helix model of DNA with the base pairs in the middle. The extraordinary discovery was announced on February 28, 1953 in their prominent articlel Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid, and the news spread quickly. A new milestone was set in molecular biology.

Aftermath

Watson and Crick, together with Maurice Wilkins, were awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1962 for their discoveries about the molecular structure of nucleic acids and their significance for the transfer of information in living matter. Rosalind Franklin, whose X-ray diffraction diagrams had contributed significantly to the decoding of the DNA structure, had already died at that time and could therefore no longer be nominated.

How I discovered DNA – James Watson, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Molecular structure of nucleic acids [PDF]

- [2] The DNA at the Nobelprize Website

- [3] Clue to chemistry of heredity found [PDF]

- [4] James D. Watson: DNA – The Secret of Life, Arrow Books, 2004.

- [5] Rosalind Franklin and the Beauty of the DNA Structure, SciHi Blog, July 24, 2014

- [6] Maurice Wilkins and the DNA, SciHi Blog, December 15, 2016

- [7] Severo Ochoa and the Biological Systhesis of RNA and DNA, SciHi Blog, September 24, 2017

- [8] James Watson at Wikidata

- [9] Francis Crick at Wikidata

- [10] James D. Watson, “The Human Genome Project: past, present, and future.” Science, 6 April 1990; 248:44-48.

- [11] How I discovered DNA – James Watson, TED2005, TED-Ed @ youtube

- [12] Watson, J. D. (1981). Gunther S. Stent (ed.). The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95075-1. (Norton Critical Editions, 1981).

- [13] Timeline of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #29 | Whewell's Ghost

Rosalind Franklins ground breaking work was given by Wilkins to the pair and undoubtedly provided the impetus for their “discovery”. She was never awarded her true recognition as she died from ovarian cancer and was therefore ineligible for her duly deserved noble prize share (no posthumous recognition). The recipients have never been courteous nor grateful enough to acknowledge her vital contribution playing to their own sense of historical importance and downplaying the true influence of her ground breaking findings. Pity this article doesn’t either.

Thank you for your valuable comment! However, we have dedicated an own article at SciHi Blog entirely to Rosalind Franklin and her contribution to the discovery of the structure of DNA [1] (as mentioned in the references of the article).

[1] Rosalind Franklin and the Beauty of the DNA Structure, SciHi Blog, July 27, 2014.

Writer lmb is correct. While you do mention the “slight” in your nice tribute to Franklin (2014), your readers should know that Franklin was supposed to attend a meeting where all the principles had gathered but was on vacation. The crucial image was shown, without her permission, and as you point out, the final idea quickly became apparent! Within about 48 hours, Watson and Crick (at a pub) had penned the famous 1953 Nature paper with only a passing mention to Franklin in the acknowledgments. She was robbed! In the 9th ed of Exercise physiology. Energy, Nutrition and Human Performance (lww.com; authors McArdle, Katch, Katch), in a chapter dealing with molecular biology and its history, we pay tribute to Franklin and further state, “. . . these revelations reveal a seldom seen but ugly side of some in the basic sciences—cutthroat ways and blind ambition run roughshod over other researchers’ contributions without proper attribution.” Highly recommend this book for insides about Franklin’s contributions: Sayre, Anne (1987) [1975]. Rosalind Franklin and DNA. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-32044-8.