Norman Ernest Borlaug (1914-2009) [Public Domain] via WikiCommons

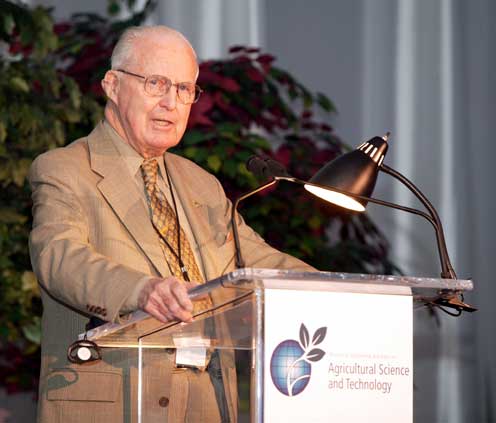

On March 25, 1914, American biologist and humanitarian Norman Ernest Borlaug was born. Borlaug led initiatives worldwide that contributed to the extensive increases in agricultural production termed the Green Revolution and has been awarded with the Nobel Peace Prize. Borlaug is often called “the father of the Green Revolution“, and is credited with saving over a billion people worldwide from starvation.

“You can’t build a peaceful world on empty stomachs and human misery.”

– Norman E. Borlaug, as quoted in [8]

Norman Borlaug – Youth and Education

Norman Borlaug was born in Cresco, Iowa, USA, the eldest of four children to Henry Oliver Borlaug and his wife Clara (née Vaala). From age seven to nineteen, he worked on the family farm, fishing, hunting, and raising corn, oats, timothy-grass, cattle, pigs and chickens. He attended a rural school in Howard County, followed by Cresco High School. Through a Depression-era program known as the National Youth Administration, he was able to enroll at the University of Minnesota in 1933. Borlaug failed the entrance exam, but was accepted to the school’s newly created two-year General College. After two quarters, he transferred to the College of Agriculture’s forestry program.

Immediately before and immediately after receiving his Bachelor of Science degree in 1937, he worked for the U.S. Forestry Service at stations in Massachusetts and Idaho. Returning to the University of Minnesota to study plant pathology, receiving a master of science degree in 1940 and Ph.D. in plant pathology and genetics in 1942. From 1942 to 1944, he was a microbiologist on the staff of the du Pont de Nemours Foundation where he was in charge of research on industrial and agricultural bactericides, fungicides, and preservatives.[1]

Research in Disease Resistant Wheat

In 1944 Norman Borlaug accepted an appointment as geneticist and plant pathologist assigned the task of organizing and directing the Cooperative Wheat Research and Production Program in Mexico. This program, a joint undertaking by the Mexican government and the Rockefeller Foundation, involved scientific research in genetics, plant breeding, plant pathology, entomology, agronomy, soil science, and cereal technology. Within twenty years he was spectacularly successful in finding a high-yielding short-strawed, disease-resistant wheat.[1] Seeking to assist impoverished farmers who struggled with diseased and low-producing crops, Borlaug experimented with novel varieties of wheat, creating disease-resistant strains that could withstand the harsh climate. That work was founded on earlier discoveries of ways to induce genetic mutations in plants, and his methods led to modern plant breeding.[4]

The Green Revolution

The Green Revolution resulted in increased production of food grains (especially wheat and rice) and was in large part due to the introduction into developing countries of new, high-yielding varieties, beginning in the mid-20th century with Borlaug’s work. At a research station at Campo Atizapan, he developed a short-stemmed (“dwarf”) strain of wheat that dramatically increased crop yields. Previously, taller wheat varieties would break under the weight of the heads if production was increased by chemical fertilizers. Borlaug’s short-stemmed wheat could withstand the increased weight of fertilized heads and was a key element in the Green Revolution in developing countries. Wheat production in Mexico multiplied threefold owing to this and other varieties.[4]

Agricultural Revolution in Asia

Following Norman Borlaug’s success in Mexico, the Indian and Pakistani goverments requested his assistance, and with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Borlaug began his agricultural revolution in Asia. With India and Pakistan facing food shortages due to rapid population growth, the importation of Borlaug’s dwarf wheat in the mid-1960s was responsible for a 60 percent increase in harvests there, helping both countries to become agriculturally self-sufficient. His work in developing countries, especially on the Indian subcontinent, is estimated to have saved as many as one billion people from starvation and death.[4]

Pakistan became self-sufficient in wheat production by 1968; India was self-sufficient in all cereal crops by 1974. Since then, grain production in both countries has consistently outpaced population growth. Borlaug’s achievements in Mexico, India and Pakistan were hailed as a Green Revolution. The scientists Borlaug had trained in Mexico and Asia spread his techniques and grains to Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and Indonesia, to continental South America and to Africa. Around the world, infant mortality rates fell and life expectancy rose. In many countries, the rising standard of living reduced social tensions and political violence.[5]

The Nobel Peace Prize

“There can be no permanent progress in the battle against hunger until the agencies that fight for increased food production and those that fight for population control unite in a common effort.”

– Norman E. Borlaug, 1970 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech

For his contributions to the world food supply, Norman Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. Borlaug continually advocated increasing crop yields as a means to curb deforestation. The large role he played in both increasing crop yields and promoting this view has led to this methodology being called by agricultural economists the “Borlaug hypothesis”, namely that increasing the productivity of agriculture on the best farmland can help control deforestation by reducing the demand for new farmland. According to this view, assuming that global food demand is on the rise, restricting crop usage to traditional low-yield methods would also require at least one of the following: the world population to decrease, either voluntarily or as a result of mass starvations; or the conversion of forest land into crop land. It is thus argued that high-yield techniques are ultimately saving ecosystems from destruction.

Following his retirement, Borlaug continued to participate in teaching, research and activism. Borlaug died of lymphoma at the age of 95, on September 12, 2009.

Juliet Christian-Smith & David Zoldoske, The Future of Irrigated Agriculture: Where’s the Water?, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Norman Borlaug, Biographical, at Nobelprize.org

- [2] J. Gillis, Norman Borlaug, Plant Scientist Who Fought Famine, Dies at 95, The New York Times, September 13,

2009. - [3] D. Biello, Norman Borlaug: Wheat breeder who averted famine with a “Green Revolution”, at Scientific American Blog, September 14, 2009.

- [4] Norman Ernest Borlaug, American scientist, at Britannica Online

- [5] Norman E. Borlaug, The Father of the Green Revolution, at Achievements.org

- [6] Norman E. Borlaug at Wikidata

- [7] Juliet Christian-Smith & David Zoldoske, The Future of Irrigated Agriculture: Where’s the Water?,

- [8] “Eat This!”, an episode of Penn and Teller’s Bullshit!; Quoted in: Gary Beene (2011) The Seeds We Sow: Kindness that Fed a Hungry World, California Colloquium on Water, UC Berkeley Events @ youtube

- [9] Rajaram, S. (2011). “Norman Borlaug: The Man I Worked with and Knew”. Annual Review of Phytopathology. 49: 17–30. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095308

- [10] Vietmeyer, Noel (2013). Our Daily Bread: the Essential Norman Borlaug. Bracing Books.

- [11] Norman Borlaug, The Green Revolution, Peace, and Humanity. 1970. Nobel Lecture, Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo, Norway. December 11, 1970.

- [12] Norman Borlaug, “Ending World Hunger. The Promise of Biotechnology and the Threat of Antiscience Zealotry“. 2000. Plant Physiology, October 2000, Vol. 124, pp. 487–90.

- [13] Borlaug, Norman E. (June 27, 2007). “Sixty-two years of fighting hunger: personal recollections”. Euphytica. 157 (3): 287–97. doi:10.1007/s10681-007-9480-9.

- [14] Timeline of Nobel Peace Prize Winners, via Wikidata