Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695)

On October 4, 1675, prominent Dutch mathematician, physicist, astronomer and inventor Christiaan Huygens patented a pocket watch. Huygens was a leading scientist of his time, who established the wave theory of light and made outstanding astronomical discoveries. He also patented the first pendulum clock in 1656, which he has developed to meet his need for exact time measurement while observing the heavens.

“…the power of this line [the cycloid] to measure time.”

– Christiaan Huygens, Horologium Oscillatorium (1673)

Christiaan Huygens – Youth and Education

Christiaan Huygens was born on 14 April 1629 in The Hague, Netherlands, into a rich and influential Dutch family. His father Constantijn Huygens was a diplomat and advisor to the House of Orange, among whose friends also were some famous scientists such as Galileo Galilei,[5] Marin Mersenne [6] and René Descartes.[7] Huygens was liberally educated at home and studied languages and music, history and geography, mathematics, logic and rhetoric, but also dancing, fencing and horse riding. From 1645-1647, Huygens studied law and mathematics at the University of Leiden with Frans van Schooten as private tutor, who brought Huygens’ mathematical education up to date, in particular introducing him to the work of Fermat on differential geometry.[9]

From 1647 until 1649 he continued to study law and mathematics but now at the College of Orange at Breda. In 1649 Huygens went to Denmark as part of a diplomatic team and hoped to continue to Stockholm to visit Descartes but the weather did not allow him to make this journey. He followed the visit to Denmark with others around Europe including Rome. Huygens’s first publications in 1651 and 1654 considered mathematical problems.

Optics and Astronomical Research

In 1654, Huygens returned to his father’s house in The Hague, and was able to devote himself entirely to research. Huygens soon turned his attention to lens grinding and telescope construction. He devised a new and better way of grinding and polishing lenses. Using one of his own lenses, Huygens detected, in 1655, the first moon of Saturn.[1,2] The following year he discovered the true shape of the rings of Saturn and explained the phases and changes in the shape of the ring in his publication In Systema Saturnium (1659). Huygens main contributions lie in the field of physics and astronomy, but this should be subject of a future article. Here instead, we want to focus on his contributions in horology.

From Astronomy to Horology

Work in astronomy required accurate timekeeping and this prompted Huygens to tackle this problem. In 1656 he patented the first pendulum clock, which greatly increased the accuracy of time measurement. The principle itself has been observed by Galileo Galilei, traditionally as a result of watching a lamp swinging the cathedral when he was a student in Pisa. Galileo later proved experimentally that a swinging suspended object takes the same time to complete each swing regardless of how far it travels. This consistency prompted Galileo to suggest that a pendulum might be useful in clocks. But it was Huygens who first made practical use of it. Huygens believed that a pendulum swinging in a large are would be more useful at sea and he invented the cycloidal pendulum with this in mind.

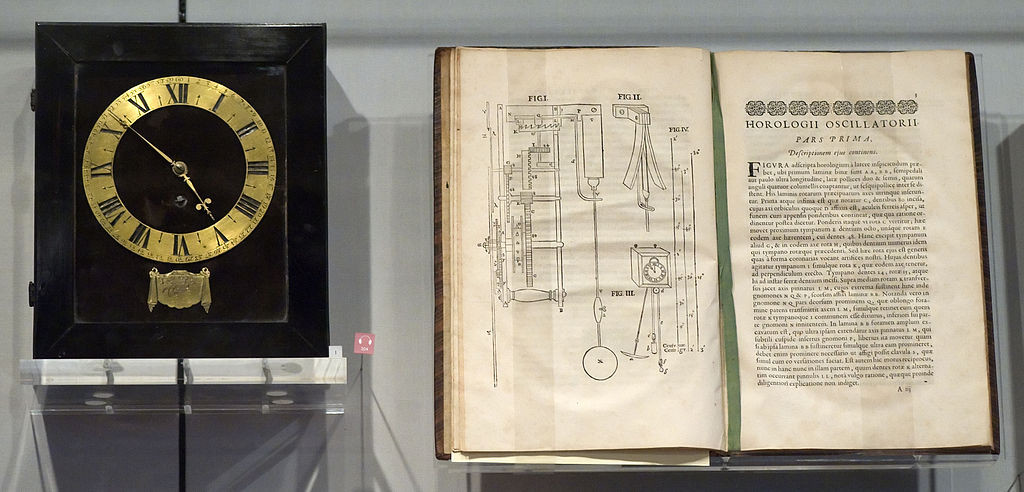

One of the first pendulum clocks designed by the inventor of the pendulum clock, French scientist Christiaan Huygens, and his treatise on the pendulum, Horologii Oscillatorii published in 1673, on display in Museum Boerhaave in Leiden, Netherlands.

The Motion of the Pendulum

Huygens built several pendulum clocks to determine longitude at sea and they underwent sea trials in 1662 and again in 1686. In the Horologium Oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum (1673) he described the theory of pendulum motion. Huygens then developed a balance spring watch in the same time as, though independently of, Robert Hooke.[9] Controversy over the priority persisted for centuries and over the next few years it distracted Huygens from extending it beyond its initial application to pocket watches. But the idea of a larger format had occurred to him from the outset, and by 1679 he was speaking openly about a spring-regulated marine clock.[4]

Further Improvements

A Huygens watch employed a spiral balance spring; but he used this form of spring initially only because the balance in his first watch rotated more than one and a half turns. He later used spiral springs in more conventional watches. Such springs were essential in modern watches with a detached lever escapement because they can be adjusted for isochronism. Watches in the time of Huygens and Hooke, however, employed the very undetached verge escapement. It interfered with the isochronal properties of any form of balance spring, spiral or otherwise.

Christiaan Huygens, Horologium oscillatorium sive de motu pendulorum, 1673

The Pocket Watch

In 1675, Huygens patented a pocket watch. The watches which were made in Paris from c. 1675 and following the Huygens plan are notable for lacking a fusee for equalizing the mainspring torque. The implication is that Huygens thought that his spiral spring would isochronise the balance, in the same way that he thought that the cycloidally shaped suspension curbs on his clocks would isochronise the pendulum.

All watches used this same basic mechanism until the first quartz crystal oscillators were developed for watches in 1969.

Walter Lewin, Lec 20: Huygens’ Principle, Interference | 8.03 Vibrations and Waves, Fall 2004 [12]

Related Work and Further Reading:

- [1] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Christiaan Huygens“, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [2] Christiaan Huygens and the Discovery of Saturn Moon Titan, yovisto Blog, March 25, 2013.

- [3] The History of Clocks

- [4] Michael S. Mahoney: Christian Huygens – The Measurement of Time and of Longitude at Sea, in Studies on Christiaan Huygens, ed. H.J.M. Bos et al. (Lisse: Swets, 1980), 234-270.

- [5] The Galileo Affair, SciHi Blog

- [6] Marin Mersenne – Mathematics and Universal Harmony, SciHi Blog

- [7] Cogito Ergo Sum – The Philosophy of René Descartes, SciHi Blog

- [8] Pierre de Fermat and his Last Problem, SciHi Blog

- [9] Robert Hooke and his Famous Observations of the Micrographia, SciHi Blog

- [10] Works by or about Christiaan Huygens at Internet Archive

- [11] Christiaan Huygens, Horologium oscillatorium (English translation by Ian Bruce) on the pendulum clock

- [12] Walter Lewin, Lec 20: Huygens’ Principle, Interference | 8.03 Vibrations and Waves, Fall 2004, For the Allure of Physics @ youtube

- [13] Timeline of Clockmakers, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #13 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: No. 443: On Ken Morrelly, the LIREDC’s highest hopes, Sputnik and the Queen of the Damned - Innovate Long Island