Achim von Arnim (1781-1831)

On January 26, 1781, German poet and novelist Carl Joachim Friedrich Ludwig Achim von Arnim was born. Together with Clemens Brentano and Joseph von Eichendorff, von Arnim was a leading figure of German Romanticism.

“Let the youth create and be joyful, let them build a house of lilies and roses as long as lilies and roses are in bloom.”

— Achim von Arnim

Achim von Arnim – Early Life

Achim von Arnim’s father was the wealthy Royal Prussian Chamberlain Joachim Erdmann von Arnim, who came from the Uckermark family branch Blankensee and was envoy of the Prussian king in Copenhagen and Dresden and later director of the Berlin Royal Opera. Arnim’s mother Amalie Caroline von Arnim, née Labes, died three weeks after his birth. Born in Berlin, Prussia, Arnim spent his childhood and youth together with his older brother Carl Otto with his grandmother Caroline von Labes in Zernikow and Berlin, where he attended the Joachimsthalsche Gymnasium from 1793 to 1798. From 1798 to 1800 he studied law, natural sciences and mathematics in Halle (Saale). While still a student, he wrote numerous scientific texts, including the attempt at a theory of electrical phenomena and essays in the annals of physics. In the house of the composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt he met Ludwig Tieck, whose literary works he admired. In 1800 Arnim moved to Göttingen to study natural sciences, where he met Johann Wolfgang von Goethe [1] and Clemens Brentano. Under their influence he turned from scientific writings to his own literary works. After completing his studies in the summer of 1801, he wrote his first novel Hollin’s Liebesleben (Hollin’s Love Life), influenced by Goethe’s Werther.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn – The Book of German Folk Songs

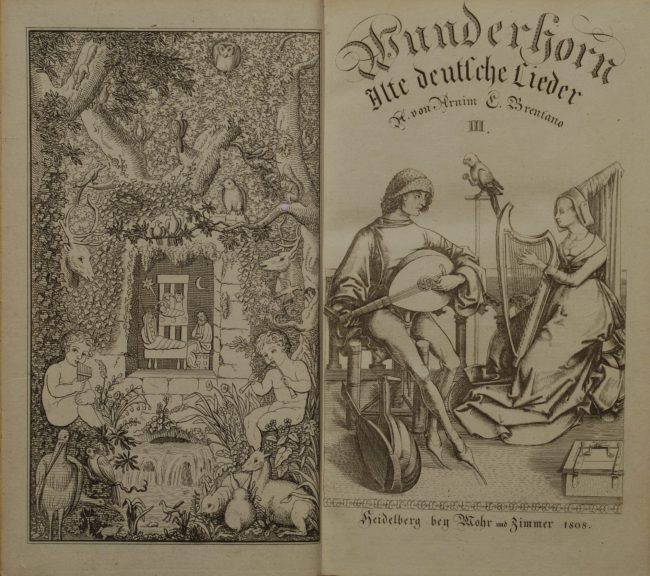

From 1801 to 1804 Arnim undertook an educational journey across Europe together with his brother Carl Otto. In 1802 he first met his later wife Bettina in Frankfurt and travelled the Rhine with Brentano. At the end of 1802 he visited Madame de Staël in Coppet and in 1803 he met Friedrich and Dorothea Schlegel for the first time in Paris.[9,10] That year Arnim travelled on to London and stayed in England and Scotland until the summer of 1804. After his return Arnim and Brentano drew up first concrete plans for the publication of a folk song collection, which finally appeared in 1805 under the title Des Knaben Wunderhorn (“The boy’s magic horn: old German songs”).[3] Arnim went through the collected songs of the collection with Goethe in Weimar, some of which had been heavily edited by Arnim and Brentano. The collection contains around 600 adaptations of German folk songs and is one of the most important testimonies to a folk poetry propagated by Romanticism. It contains love, children’s, war and wandering songs from the Middle Ages to the 18th century. Goethe recommended Des Knaben Wunderhorn for reading across all social classes, as it seemed just as suitable for the simplest cuisine as for the piano of scholars. The younger followers of Romanticism, strongly moved by national feeling, devoted themselves to the collection and study of the origins of the Germanic past in folk songs, fairy tales, myths, legends, and Germanic poetry (Edda). Everything untouched by the negative effects of modern civilization in their eyes was considered good and helpful for the “recovery of the nation”.

Bettina von Arnim

Romanticism and Nationalism

The publication of further volumes was delayed by the Franco-German war. After the defeat of Prussia at Jena and Auerstedt Arnim followed the escaped royal court to Königsberg. There he made political suggestions in the circle around the reformer Freiherr vom Stein. Arnim moved to Heidelberg in 1808, Clemens Brentano followed him and there they completed their work on the folk song collection. The second and third volumes of the Wunderhorn were published and Arnim also wrote essays for the Heidelberg Yearbooks. In the circle of Romantics around Joseph Görres, to whom the Heidelberg Romanticism owes its name, Arnim published the Zeitung für Einsiedler (newspaper for hermits), in which Tieck, Friedrich Schlegel, Jean Paul,[11] Justinus Kerner and Ludwig Uhland worked alongside Brentano, Görres and the Brothers Grimm.[4] This circle turned mainly to the Middle Ages for political reasons in order to establish a national unity over this epoch, the aesthetic aspect being of less interest. From 1809 Arnim lived in Berlin, where he unsuccessfully applied for an office in the Prussian civil service.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn. Cover of the first edition, 1805

The Clash with Goethe

In Berlin Arnim published his collection of short stories Der Wintergarten, (The winter garden) worked for Kleist‘s Berliner Abendblätter, and in 1811 founded the Deutsche Tischgesellschaft, a patriotic association to which numerous politicians, professors, military personnel, and artists of Berlin society belonged and in which only men baptized Christian had access.[5] In 1810 Arnim got engaged to Bettina, the couple got married on March 11, 1811. The Arnims had seven children. However, the couple lived mostly separated, they lived in Berlin, he on his estate Wiepersdorf. Soon after the wedding they travelled together to Weimar to visit Goethe. A fierce quarrel between Bettina and Goethe’s wife Christiane led to a lifelong alienation between Goethe and Arnim.[6,12] In 1813, during the wars of liberation against Napoleon, Arnim commanded a Berlin Landsturmbataillon as captain. From October 1813 to February 1814 he was editor of the Berlin daily newspaper Der Preußische Correspondent, but gave up this position due to disputes with the first editor Barthold Georg Niebuhr.

A. von Arnim, C. Brentano, Des Knaben Wunderhorn, Frontispiece and title-page, Volume 3, published in 1808,

H.-P. 06:28, 30. Jun. 2008 (CEST), CC BY-SA 2.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

Later Life

From 1814 until his death in 1831 Arnim lived predominantly – interrupted by occasional travels and longer stays in Berlin – on his estate in Wiepersdorf and took part in Berlin’s literary life with numerous articles and stories in newspapers, magazines and almanacs as well as with book publications. His wife and children lived mainly in Berlin. The first volume of his novel Die Kronenwächter (The Crownguards) appeared in 1817. The story takes place in Southwest Germany at the beginning of the 16th century. The two protagonists Berthold and Anton prove to be totally incompetent and unworthy descendants of the Staufer. In 1820 Arnim Ludwig visited Uhland, Justinus Kerner, the Brothers Grimm and for the last time Goethe in Weimar. In the last years of his life Arnim had to struggle again and again with financial problems. There was no further great literary success.

Achim von Arnim died from cerebral apoplexy on 21 January 1831 in Wiepersdorf.

The Works of Achim von Arnim

Arnim’s novellas bear witness to the author’s turning to the supernatural. The story Isabella of Egypt mixes fiction and reality and thus anticipates elements of surrealism; the dreamlike fantasy is connected with historical references. Poetologically, Arnim placed his literature at the service of political renewal, which he did not want to realize through political work but through art. This is why he often revived folk fabrics. Arnim’s unfinished novel The Crownguards pushed the renewal of the historical novel in Germany. It shows grievances of Arnim’s present in the form of a historical narrative.

The contemporary judgements about Arnim differed widely: Heinrich Heine wrote that Arnim was “a great poet and one of the most original heads of the romantic school. Friends of the fantastic would like this poet more than any other German writer“. Goethe, on the other hand, saw Arnim’s work as “a barrel to which the cooper had forgotten to fasten his hoops”.

„Alles geschieht in der Welt der Poesie wegen, das Leben mit einem erhöhten Sinne und in einem erhöhten Sinne zu leben, die Geschichte ist der Ausdruck dieser allgemeinen Poesie des Menschengeschlechts, das Schicksal führt dieses grosse Schauspiel auf.”

(Everything happens in the world because of poetry, living life with an elevated sense and in an elevated sense, history is the expression of this general poetry of the human race, destiny performs this great spectacle.)

— Achim von Arnim in a letter to Clemens Brentano, 1802

Jonathan Bate, The Origins of Romanticism, [13]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Life and Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, SciHi Blog

- [2] Bettina von Arnim and the Romantic Era’s Zeitgeist, SciHi Blog

- [3] Clemens Brentano, Achim von Arnim, Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

- [4] The Brothers Grimm and the Göttingen Seven, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Murder-Suicide of Heinrich von Kleist, SciHi Blog

- [6] Finally, Goethe Got Married – The Story of Christiane Vulpius, SciHi Blog

- [7] Works by or about Achim von Arnim at Wikisource

- [8] Achim von Arnim at Wikidata

- [9] The Conversational Eloquence of Madame de Staël, SciHi Blog

- [10] The Emanzipation of Dorothea von Schlegel, SciHi Blog

- [11] Dreams, Travelling, and Humoresques – The Literary Life of Jean Paul, SciHi Blog

- [12] Bettina von Arnim and the Romantic Era’s Zeitgeist, SciHi Blog

- [13] Jonathan Bate, The Origins of Romanticism, Gresham College @ youtube

- [14] Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- [13] Timeline for Achim von Arnim, via Wikidata