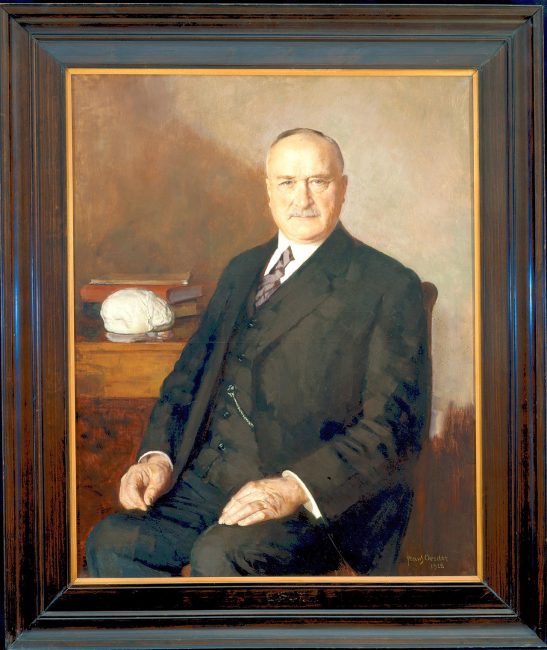

Eugene Dubois (1858-1940), Portrait by Frans Oerder, 1928

On January 28, 1858, Dutch paleoanthropologist and geologist Eugene Dubois was born. Dubois earned worldwide fame for his discovery of Pithecanthropus erectus (later redesignated Homo erectus), or Java Man. Although hominid fossils had been found and studied before, Dubois was the first anthropologist to embark upon a purposeful search for them.

Eugene Dubois – Early Years

Dubois was born in Eijsden, near Limburg, Netherlands, where his father, Jean Dubois, was an apothecary, later the mayor. Interested in all phenomena of the world of nature, Dubois as a child already explored the underground limestone mines of Mount Saint Peter and amassed collections of plant parts, stones, insects, shells, and animal skulls. He attended school in Roermond, where he attended lectures on Charles Darwin‘s new theory of evolution given by the German biologist, Karl Vogt.[5]

In 1877, Dubois enrolled to study medicine at the University of Amsterdam, graduating in 1884. Dubois was appointed anatomy lecturer at Amsterdam University. He declined an offer from the University of Utrecht of a position as a docent. Instead, at the invitation of his anatomy instructor, Max Fürbringer, he decided to further deepen his studies in comparative anatomy and became Fürbringer’s assistant. In 1885 he investigated the larynx of vertebrates, which led him to develop a hypothesis of the evolution of this organ. Nevertheless, his chief interest was in human evolution, influenced by German biologist Ernst Haeckel, who reasoned that there must be intermediate species between ape and human.[6]

Fossil Hunting and the Dutch East Indies

Inspired by the fresh discovery of new Neanderthal fossils at the Belgian town of Spy,[7] he spent his vacation fossil hunting in the vicinity of his birthplace. In the Henkeput near the village of Rijckholt, he actually found some prehistoric human skulls. Reasoning that the origins of the human species must be in the tropics, he gave up his current position in order to travel to the Dutch East Indies and look for fossils of human ancestors. It is not really clear, why Eugene Dubois made this decision. Some believe that Dubois disliked his teaching position. He possibly chose the East Indies, now Indonesia, because his like him many other scientists also believed that humans have evolved in the tropics. Together with his wife and newborn daughter he moved to the Dutch colony to search for the missing link in human evolution.

Sumatra and First Studies

He joined the Dutch Army as a medical officer and Dubois along with his family arrived at Sumatra in late 1887. Since the first studies conducted by Dubois in his spare time were successful, the government assigned a team of engineers and laborers to help him. Unfortunately, the area was densely forested and they were short on water. After many workers ran away and one of his engineers died, the scientist only were able to excavate a few insignificant fossils. Thus, he decided that in java they might have better chances of success. He was transferred there in 1890 and began searching near Solo River with a new team which proved to be more successful.

The Discovery of the Java Man

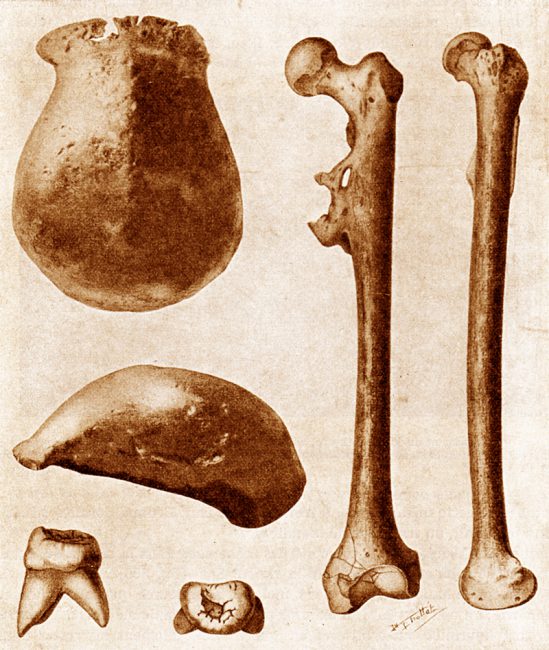

In September of the same year, at Koedoeng Broeboes, Dubois’ workers found a human-like fossil. In the next year, Dubois found a tooth, a skullcap, the fossil which became widely known as the Java Man. Dubois published works on his fossils which he named ‘Pithecanthropus erectus‘ in 1894. He described it as something between an ape and a human. The scientist started to promote his findings one year later in Europe, and even though some contemporaries welcomed his work, most disagreed with Dubois. However, Eugene Dubois kept promoting his work, traveling through Europe, and his position received more and more support. In 1891 he also was the first to describe Dubois’ antelope (Duboisia santeng) from the Pleistocene of Java, which was placed in the genus Duboisia named in his honor in 1911. In 1897, Eugene Dubois was awarded an honorary doctorate in botany and zoology by the University of Amsterdam, and in 1899 became a professor there in crystallography, mineralogy, geology and paleontology.

The three main fossils of Java Man found in 1891–92: a skullcap, a molar, and a thighbone, each seen from two different angles.

Later Life

After ceasing to discuss Java Man and basically hiding the fossils at his home, Dubois allowed access to Java Man in the 1920s. It became a gain a topic of debate after similar fossils had been found. In 1929, the first Peking Man fossils were excavated and in the 1930s, other pithecanthropine fossils were found in Java at Sangiran. In 1919 Dubois became member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Dubois was a difficult person to deal with, and as he grew older, his unpleasant character traits came to the fore. As a result, he became increasingly isolated from the scientific world. Eugène Dubois died in 1940 and is buried in the general cemetery of Venlo. Dubois is considered to be the first researcher who was purposefully on the search for human ancestors (since 1885). He was one of the first to recognize that brain size and body weight are in an allometric relationship.

Origins of Genus Homo–Australopiths and Early Homo; Variation of Early Homo; Speciation of Homo, [12]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Eugene Dubois Biography

- [2] Fossil Hominids, Human Evolution: Thomas Huxley & Eugene Dubois at www.understandingevolution.org

- [3] The Ape Men II – Eugene Dubois and the Java Man

- [4] Eugene Dubois at Britannica

- [5] Charles Darwin’s ‘On the Origin of Species’, SciHi Blog

- [6] Ernst Haeckel and the Phyletic Museum, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Discovery of the Neanderthal Man, SciHi Blog

- [8] Biography at the Eugene Dubois Foundation

- [9] Eugene Dubois at Wikidata

- [10] Shipman, P.; 2001: The Man Who Found the Missing Link. The Extraordinary Life of Eugène Dubois, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

- [11] The discovery and re-discovery of Eugène Dubois”, Radio Netherlands Archives, November 7, 2000

- [12] Origins of Genus Homo–Australopiths and Early Homo; Variation of Early Homo; Speciation of Homo, University of California Television (UCTV) @ youtube

- [13] Timeline of Paleoanthropoligists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Wheel’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #29 | Whewell's Ghost