Nicolaus Copernicus(1473 – 1543)

On February 19, 1473, Renaissance mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus was born, who established the heliocentric model, which placed the Sun, rather than the Earth, at the center of the universe. With the publication of his research he started the so-called Copernican Recolution, which started a paradigm shift away from the former Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which postulated the Earth at the center of the universe, towards the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of our Solar System. In 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus published his treatise De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), which presented a heliocentric model view of the universe. Overall, it took about 200 years for a heliocentric model to replace the Ptolemaic model. But, Copernicus was not the first to propose a heliocentric model. Actually, even the ancient Greek philosophers argued about, as e.g. Aristarchus of Samos in the 3rd century BCE,[6] who had developed some theories of Heraclides Ponticus (speaking of a revolution by Earth on its axis) to propose what was, so far as is known, the first serious model of a heliocentric solar system.

“Finally we shall place the Sun himself at the center of the Universe. All this is suggested by the systematic procession of events and the harmony of the whole Universe, if only we face the facts, as they say, “with both eyes open.”

— Nicolaus Copernicus, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (1543), as quoted in [15]

Nicolaus Copernicus – Early Years

Nicolaus Copernicus was born in the city of Thorn (modern Toruń), in the province of Royal Prussia, in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, as the son of successful merchants. He was well educated, speaking Latin, German, and Polish fluently, wherefore most of his later publications were published in Latin. In 1491, Copernicus began his studies at the University of Krakow gathering the basic knowledge in mathematics and astronomy. Besides his astronomical interests, Copernicus evolved a great interest in the philosophical ideas of Aristotle, works by Euclid,[7] or Johannes Regiomontanus‘ Tabulae directionum, gathering a great private library.[8] Even though the time at Krakow University was important to his future career in concerns of his knowledge and experience, he left the institution without a degree.

Neoplatonism and Astronomy in Bologna

In 1495 Copernicus was appointed canon of the cathedral school in Frauenburg. His uncle Watzenrode sent him to the University of Bologna, where he began to study law in the winter semester of 1496/1497, but did not yet earn an academic degree. In Bologna Copernicus studied Greek with Urceus Codrus and astronomy with Domenico Maria da Novara, who taught him new theories on the movement of planets. There he acquired the title of Magister artium. Novara introduced him to the world of thought of Neoplatonism, for which the sun was of great importance as the material image of God or the One.

Rome, Padua and Ferrara

In 1500 Copernicus left Bologna and spent some time in Rome on the occasion of the Holy Year before returning to Frauenburg in Warmia in 1501. He asked for permission to extend his studies in Italy and began studying medicine at the University of Padua that same year. At the same time he continued his law studies. Copernicus received his doctorate in Canon Law (Doctor iuris canonici) from the University of Ferrara on 31 May 1503. He did not obtain an academic degree in medicine.

The Warmia Canonry

In 1503 he returned to Warmia and began working as a secretary and doctor for his uncle Lucas Watzenrode, the prince-bishop of Warmia. Copernicus became a doctor and his uncle got a job at the canonry in Frauenburg. Despite the difficult situation in Prussia, where towns and people fought for and against the Catholic government, Watzenrode, as prince-bishop and sovereign of the country, and his nephew Copernicus were able to preserve the independence of Warmia from the Order and the self-governing powers of the Polish Crown. Copernicus was elected Chancellor of the Warmia Canonry in 1510, 1519, 1525 and 1528. In the armed conflicts between the Teutonic Order and Poland, Copernicus, like his uncle, represented the side of the Prussian Federation, which was allied with Poland against the Teutonic Order.

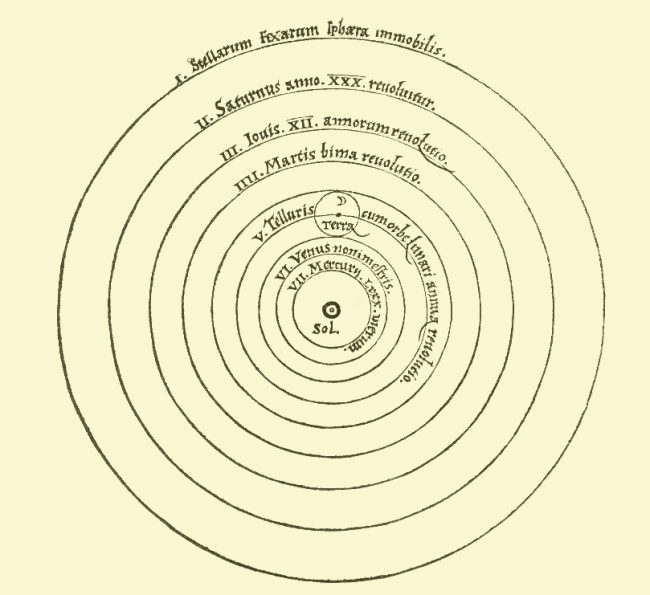

Heliocentric model from Nicolaus Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

The Heliocentric Model

The work on the heliocentric theory began during Copernicus’ time as his uncles’ secretary in Heilsberg. Nicolaus Copernicus had already made his ideas accessible to a small circle of experts around 1509 with the Commentariolus. He wrote in it that the mathematical details still had to be worked out. In his brief foreword, Copernicus first praised the theory of homocentric spheres created by Eudoxos of Cnidus and further developed by Callippus of Cyzicus, which made it possible to describe the irregular movements of the planets observed in the sky by means of compound regular circular movements. At the same time, however, he complained that they were not sufficiently consistent with the results of the observations. The epicyclic theory of Claudius Ptolemy attested Copernicus a good prediction of the position of the planets in the sky, but did not agree with its task of regularity of planetary motion.

Copernicus attributed his considerations on how to save a perfectly uniform circular motion of the planets to the following “principles” listed after the preface (here only the first three):

- For all heavenly circles or spheres there is not only one centre.

- The center of the earth is not the center of the world, but only the center of gravity and the moon’s orbit.

- All orbits surround the sun as if it were in the middle, and therefore the center of the world is near the sun.

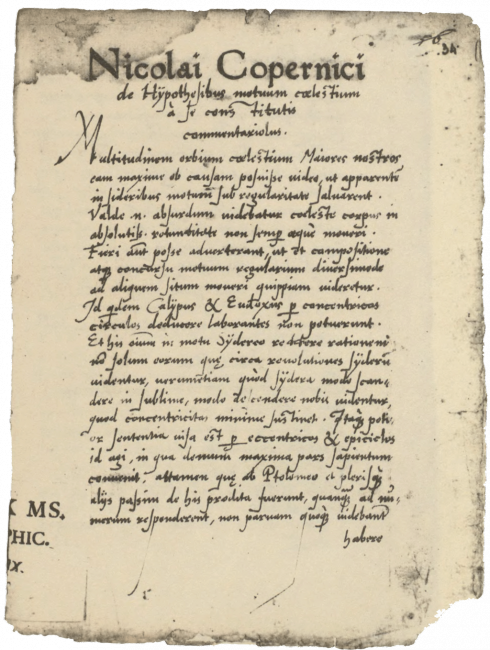

However, it was not intended to be published at any time. Only few fellow astronomers were supposed to read and contribute to his ideas. Nothing is known about the distribution of Commentariolus during Copernicus’ lifetime and its influence on contemporary astronomy. In Tycho Brahe‘s 1602 published work Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata a short reference to the Commentariolus can be found.

Sheet 34 of the manuscript 10530 from the Austrian National Library with the title Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus

De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium

Around 1512 Pope Leo X presented the possible calendar reform for discussion. Since the mean length of a year in the Julian calendar did not correspond exactly to that of a solar year, the date of the winter solstice had shifted in the course of the centuries by ten days. The Frauenburg canon Nicolaus Copernicus said that astronomical theory had to be corrected before the question of calendar reform could be addressed.[17] The manuscript ofDe revolutionibus orbium coelestium held Copernicus back for a long time. It is believed that he was either afraid to ridicule himself with such an absurd theory or that he felt it was not opportune to reveal such secrets. In 1538 Johannes Schöner [10] and Johannes Petreius commissioned Georg Joachim Rheticus,[11] who was in Nuremberg for a study visit, to visit Copernicus in Frauenburg and persuade him to have his work printed. Rheticus stayed with Copernicus from 1539 to 1541. In 1540 he announced the ideas of Copernicus in the Narratio Prima. Finally he succeeded in persuading Copernicus to print and publish De revolutionibus. Andreas Osiander added an anonymous foreword to the manuscript, according to which the heliocentric world view does not have to be true or plausible, but merely has the benefit of simplifying astronomical calculations. Johannes Kepler exposed Osiander’s “falsification” by means of notes in the copy of the Nuremberg astronomer Hieronymus Schreiber.

Contemporary Criticism

One of the first to neglect Copernicus’ heliocentric theory was the Catholic Church’s chief censor. Others rejected the thought of mathematical physics, unable to foresee that Copernicus’ theory would change the field of physics back then critically. Theologians rejected the new world view because in some places it contradicted the Bible. In this context, it is often quoted that Martin Luther, who, after a common translation, called Copernicus a “fool”, had an absurd idea of the movement of the earth, which the biblical passage Joshua 10, 12-13 would oppose. However, protestant reformer Philip Melanchthon eventually saw the theory’s importance and the need to teach those wherefore the University of Wittenberg became a center where the heliocentric system was to be studied. Tycho Brahe, one of the greatest astronomers before the invention of the telescope appreciated Copernicus’ efforts, but rejected his system, wherefore he developed his own called the ‘geoheliostatic’ system in which the two inner planets revolved around the sun and that system along with the rest of the planets revolved around the Earth.

Legacy and Death

On the long run, Copernicus’ system was widely accepted and caused the so called ‘Copernican Revolution’, a now often used metaphor supporting modern developments. Toward the close of 1542, Nicolaus Copernicus was seized with apoplexy and paralysis, and he died at age 70 on 24 May 1543. Legend has it that he was presented with the final printed pages of his Dē revolutionibus orbium coelestium on the very day that he died, allowing him to take farewell of his life’s work. He is reputed to have awoken from a stroke-induced coma, looked at his book, and then died peacefully.

It was only when Galileo Galilei advocated the heliocentric world view that the Inquisition, under the leadership of Robert Bellarmin, became interested in the work. He considered it dangerous to place the human mind above the divine power and the wording of the Bible, as long as it was not proven that the Bible was wrong. It was, however, a letter published in 1615 by the Carmelite theologian Paolo Antonio Foscarini (1565-1616), in which this Copernicus’s view of the world tried to reconcile with the views of the Church, which led to De revolutionibus orbium coelestium being suspended from the Index Congregation in a decree of 5 March 1616. In 1620, the Index Congregation demanded twelve corrections to the work, in the sense that the hypothesis character of the theory was emphasized. If these corrections were made, however, the use of the work was still permitted.

ASTR 302 Lecture 2: The Copernican Revolution, [14]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Nicolaus Copernicus at Stanford

- [2] Nicolaus Copernicus at NASA

- [4] Nicolaus Copernicus at Space.com

- [5] The Galileo Affair , SciHi Blog

- [6] Aristarchus of Samos – Putting the Sun at the Right Place, SciHi Blog

- [7] Euclid – the Father of Geometry, SciHi blog

- [8] Regiomontanus – Forerunner of Modern Astronomy, SciHi Blog

- [9] Tycho Brahe – The Man with the Golden Nose , SciHi Blog

- [10] Johannes Schöner and his Globes, SciHi Blog

- [11] Georg Joachim Rheticus’ Achievements for Astronomy, SciHi Blog

- [12] And Kepler Has His Own Opera – Kepler’s 3rd Planetary Law, SciHi Blog

- [13] Nicolaus Copernicus at Wikidata

- [14] ASTR 302 Lecture 2: The Copernican Revolution, Rob Park @ youtube

- [15] Thomas S. Kuhn, The Copernican Revolution : Planetary Astronomy in the Development of Western Thought (1957)

- [16] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Nicolaus Copernicus”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [17] Copernicus and the Calendar, The Renaissance Mathematicus, Oct 28, 2014.

- [18] Science contra Copernicus, The Renaissance Mathematicus, Oct 7, 2015.

- [19] Timeline for Nicolaus Copernicus, via Wikidata

Pingback: Heliocentric vs. Geocentric Blog Post #4 – Joliet Junior College – Astronomy 101 class blog