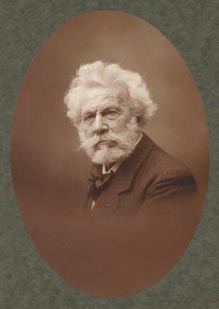

Nicolas Camille Flammarion (1842-1925)

On February 26, 1848, French astronomer and author Nicolas Camille Flammarion was born. He maintained a private observatory, where he studied double and multiple stars, the moon and Mars. He is best known as a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and works on psychical research and related topics.

“May we attribute to the color of the herbage and plants, which no doubt clothe the plains of Mars, the characteristic hue of that planet, which is noticeable by the naked eye, and which led the ancients to personify it as a warrior?”

— Camille Flammarion, in ‘Mars, by the Latest Observations’, Popular Science (Dec 1873), 4, 190.

Camille Flammarion – Early Years

Camille Flammarion was born in Montigny-le-Roi, Haute-Marne, France, of humble parents. He was a precocious boy mastering to read and to write already at the age of four. At the age ten, Flammarion was placed in a seminary, and continued his education under the care of the Jesuits. At the age 15, he was apprenticed to an engraver, and worked in his shop for some months. Whilst thus engaged, however, he managed to continue his studies, mastered English and the classics, and was able earn the degree of bachelor, as well as his matriculation to the Polytechnic School, and at the age of sixteen to enter the Paris observatory as pupil astronomer.

Influences

As a young man, Flammarion was exposed to two significant social movements in the western world: the thoughts and ideas of Charles Darwin [3] and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck,[4] and the rising popularity of spiritism with spiritualist churches and organizations appearing all over Europe. He was influenced by Jean Reynaud and his Terre at ciel (1854), which described a religious system based on the transmigration of souls believed to be reconcilable with both Christianity and pluralism. He was convinced that souls after the physical death pass from planet to planet, progressively improving at each new incarnation.

Contributions to Astronomy

Flammarion soon lost his position at the Observatory and worked for the Institut de Longitudes from 1862 to 1867; in 1867 he made nine air journeys by balloon for scientific observations; then he returned to the Observatory where he took part in a project to systematically observe double stars. The result of the project was a catalogue of 10,000 double stars, which was published in 1878. Flammarion also observed the Moon and Mars. In 1873 he proposed the thesis that the red coloration of Mars was due to vegetation. In 1877, he came across an edition of the Messier catalogue in an antiquarian bookshop which contained handwritten notes and annotations by Charles Messier.[9] He then revised the catalogue and found that Messier’s object M102 corresponded to the galaxy NGC 5866. In 1921, he added M104, known as the Sombrero Galaxy, to the Messier Catalogue.

The Cosmogony of the Universe

“[Urbain Jean Joseph] Le Verrier—without leaving his study, without even looking at the sky—had found the unknown planet [Neptune] solely by mathematical calculation, and, as it were, touched it with the tip of his pen!”

— Camille Flammarion, in Camille Flammarion, Astronomy (1914), 171

According to [1] Flammarion at that time was already the author of a work entitled The Cosmogony of the Universe greatly admired by famous astronomer Urbain Le Verrier,[5] to whose influence he principally owed his admission to the observatory. There, Flammarion was attached to the Bureau des Calculs, and had the good fortune to be able to make certain observations of comets which have been described as the most interesting that have been made during this century. At the same time he found time to write his next work, The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds. (1862).

Imaginary Worlds

In Real and Imaginary Worlds (1864) and Lumen (1887), he described a range of exotic species, including sentient plants which combine the processes of digestion and respiration. This belief in extraterrestrial life, Flammarion combined with a religious conviction derived from the writings of Jean Reynaud and their emphasis upon the transmigration of souls.

Metempsychosis

Influenced by his fellow Frenchman Allan Kardec, Flammarion became interested in psychical studies, which also influenced some of his science fiction writings, where he would write about his beliefs in a cosmic version of metempsychosis. Among other things, Flammarion believed that all planets went through more or less the same stages of development, but at different rates depending on their sizes. Flammarion approached spiritism, psychical research and reincarnation from the viewpoint of the scientific method. He had studied mediumship and wrote “It is infinitely to be regretted that we cannot trust the loyalty of mediums. They almost always cheat“.

The Unknown

However, Flammarion a believer in psychic phenomena attended séances and produced in his book alleged levitation photographs, which were considered only little convincing. His book The Unknown (1900) received a negative review due to a lack of critical judgment in the estimation of evidence. After two years investigation into automatic writing Flammarion wrote that the subconscious mind is the explanation and there is no evidence for the spirit hypothesis. Flammarion believed in the survival of the soul after death but wrote that mediumship had not been scientifically proven. He also believed that telepathy could explain some paranormal phenomena.

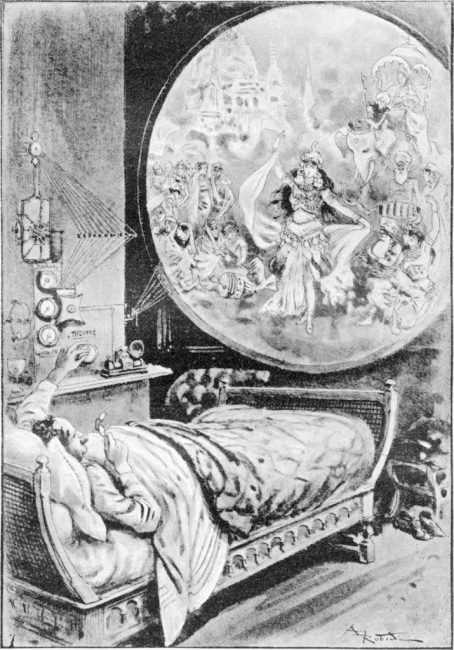

“Telefonoscope” from La Fin du Monde, 1894

Science and Science Fiction

The fusion of science, science fiction and the spiritual influenced other readers as well. With great commercial success he blended scientific speculation with science fiction to propagate modern myths such as the notion that “superior” extraterrestrial species reside on numerous planets, and that the human soul evolves through cosmic reincarnation. Authors such as Edgar Rice Burroughs, Olaf Stapledon are referring to him and Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (1913) has a lot in common with Flammarion’s worries that the tail of Halley’s Comet would be poisonous for earth life.[6]

Haunted Houses

In the 1920s Flammarion, a member of the Theosophical Society, changed some of his beliefs on apparitions and hauntings but still claimed there was no evidence for the spirit hypothesis of mediumship in Spiritism. In his 1924 book Haunted Houses he came to the conclusion that in some rare cases hauntings are caused by departed souls whilst others are caused by the “remote action of the psychic force of a living person.

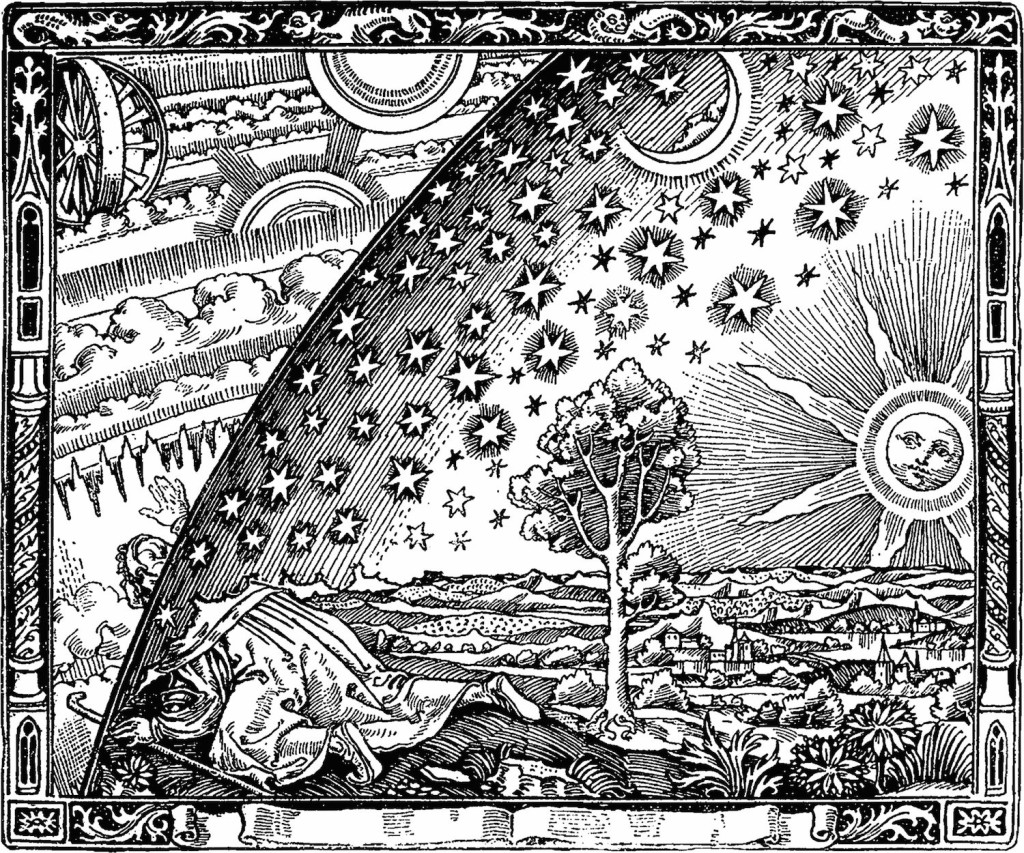

Famous engraving in Camille Flammarion’s 1888 book L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire

The Flammarion Engraving

However, usually we are dealing with so-called ‘serious’ scientists. Why do we mention Camille Flammarion, who besides being an author of popular books believed some esoteric parapsychological phenomena? Well, one reason thereof is the so-called Flammarion Engraving, which is also the title picture of this article. The Flammarion engraving is a wood engraving by an unknown artist, so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion’s 1888 book L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire The engraving has often, but erroneously, been referred to as a woodcut. It has been used to represent a supposedly medieval cosmology, including a flat earth bounded by a solid and opaque sky, or firmament, and also as a metaphorical illustration of either the scientific or the mystical quests for knowledge. In 1957, astronomer Ernst Zinner claimed that the image dated to the German Renaissance, but he was unable to find any version published earlier than 1906. Further investigation, however, revealed that the work was a composite of images characteristic of different historical periods, and that it had been made with a burin, a tool used for wood engraving only since the late 18th century. Nevertheless, I like the picture of the man looking beyond his earthly horizon and actually, I am using this picture also as recurring illustration in many of my university lectures.

Later Years

Flammarion published about 50 popular science works, including L’astronomie Populaire in 1879, of which 100,000 editions were sold, and La Planète Mars (Volume 1 1892, Volume 2 1909), in which he supported the existence of the Mars canals, which were built by a highly developed culture, and encouraged amateur astronomers to make their own observations. He also wrote fantastic stories, including Uranie (1889; Urania) and Stella (1897). In La Fin du Monde (1894, The End of the World), scientific and fantastic elements mix in describing the future of humanity in the 25th century and 10 million years from now. The novel inspired, among others, the Paris Surrealists, such as Max Ernst or Wolfgang Paalen. In 1887 Flammarion founded the Société Astronomique de France. He was very well-read and, throughout his life, compiled an extensive astronomical library, which by 1910 comprised 10,000 volumes. Camille Flammarion died on 3 June 1925 at age 83 in Juvisy-sur-Orge, France.

Carl Sagan: The Challenging Solar System. The Royal Institution, 1994, [13]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] R. H. Sherard: Flammarion The Astronomer – His Home, His Manner of Work, his Life, McClure’s Magazine (1894)

- [2] Flammarion, Camille (1842-1925), Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, 2001.

- [3] Charles Darwin’s ‘On the Origin of Species’, SciHi Blog, November 24, 2012.

- [4] Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the Evolution, SciHi Blog, August 1, 2015.

- [5] Neptune, Oceanos, or ‘Le Verrier’ – How to name a new planet?, SciHi Blog, June 9, 2012.

- [6] Edmond Halley and his famous Comet, SciHi Blog, November 8, 2012.

- [7] Camille Flammarion at Wikidata

- [8] Camille Flammarion at Reasonator

- [9] Charles Messier and the Nebulae, SciHi Blog

- [10] Works by or about Camille Flammarion at Internet Archive

- [11] Works by Camille Flammarion at LibriVox

- [12] Newspaper clippings about Camille Flammarion in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [13] Carl Sagan: The Challenging Solar System. The Royal Institution, 1994, NATURE 125th Anniversary Symposium: Our Place in Nature, the Evolution of our World, Stephen Heliczer FRAS @ youtube

- [14] Timeline of French Science Fiction Writers, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol: #37 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: From Books Bound in Human Skin to Occult Texts, These Are Literature’s Most Macabre, Surprising and Curious Creations | videshibatmya.com

Pingback: From Books Bound in Human Skin to Occult Texts, These Are Literature's Most Macabre, Surprising and Curious Creations - iBooks.ph

What is most interesting about his method is what Figuier himself would define as part of his popularization formula: a “science taught by history”, where according to the 18 model based on the idea of progress and positive knowledge it was possible to go from the simple to the complex, at the same time making the subject matter interesting and informative for his readers. It was not his place to view himself as an original thinker and a specialist in the subject, rather, he presented the “inventors”, the geniuses, and the many scholars who contributed to a certain fact or scientific process highlighted as a discovery or invention. His role was to gather documents and records, “putting random material in order”, as he used to say. In this regard, his function as a “popularizer” was different from that of a specialist and defined a role particular to mediators. This distinction between the functions of an academic scientist and of a mediator, which came to bear on the authority of scientific writings, was noticed by another important popularizer, Camille Flammarion, when he stated that “the great danger for the popularizer is becoming ‘vulgar’ when the intention is to become ‘popular’, and this danger, because of which many lost their authority, forewarned a great number of readers about those who accept this role”.