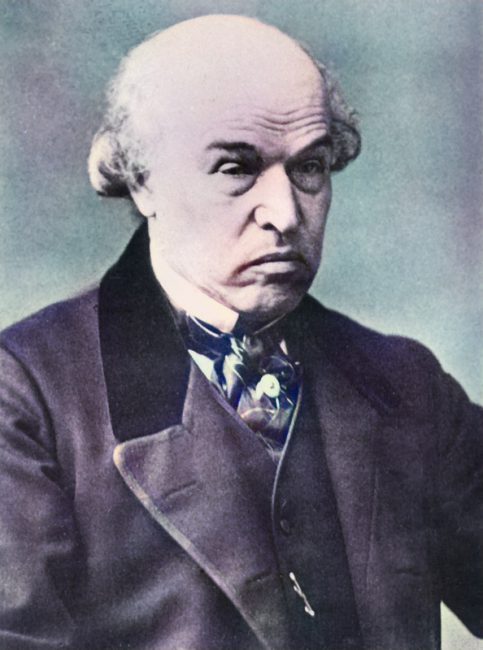

Sir William Jenner, 1st Baronet (1815 – 1898)

On January 30, 1815, English physician Sir William Jenner was born. Jenner is primarily known for having discovered the distinction between typhus and typhoid. While “typhoid” means “typhus-like”, typhus and typhoid fever are distinct diseases caused by different genera of bacteria.

“How often have I seen in past days, in the single narrow chamber of the day-labourer’s cottage, the father in the coffin, the mother in the sick-bed in muttering delirium, and nothing to relieve the desolation of the children but the devotion of some poor neighbour, who in too many cases paid the penalty of her kindness in becoming herself the victim of the same disorder.”

— William Budd on Typhoid Fever, as quoted in [9]

William Jenner – Early Years

William Jenner was born in Chatham, North Kent, in South East England. He attended University College, London where he studied medicine. Jenner was further apprenticed to a surgeon in Marylebone. William Jenner was appointed surgeron to the Royal Maternity Charity, Finsbury Square while he continued to study. Jenner received his M.D. degree in 1844 and became a consultant. In 1859, William Jenner published a work titled On the Identity or Non-Identity of Typhoid and Typhus Fevers. Much of Jenner’s success built on that work. Already in 1847 Jenner started to investigate cases of continued fever at the London Fever Hospital. These studies later enabled him to make the distinction between typhus and typhoid.

A Brief History of Typhus

The first reliable description of the disease appears in 1489 AD during the Spanish siege of Baza against the Moors during the War of Granada (1482–1492). These accounts include descriptions of fever; red spots over arms, back, and chest; attention deficit, progressing to delirium; and gangrenous sores and the associated smell of rotting flesh. During the siege, the Spaniards lost 3,000 men to enemy action, but an additional 17,000 died of typhus. Typhus was presumably known as Gaol Fever which appeared heavily during the English Civil War, the Thirty Years’ War, and the Napoleonic Wars. During the year without summer in the early 19th century, a typhus epidemic killed thousands in Europe and in Canada, the typhus epidemic of 1847 killed more than 20.000 people from 1847 to 1848, mainly Irish immigrants in fever sheds and other forms of quarantine, who had contracted the disease aboard the crowded coffin ships in fleeing the Great Irish Famine.

.. and Typhoid Fever

The typhoid fever is believed to have killed one-third of the population of Athens, including their leader Pericles. Following the plaque back then, the power shifted from Athens to Sparta, ending the Golden Age of Pericles that had marked Athenian dominance in the Greek ancient world. In later years, it is assumed that the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, died out from typhoid and that the fever killed more than 6.000 settlers in the New World between 1607 and 1624. During the American Civil War, 81.360 Union soldiers died of typhoid or dysentery, far more than died of battle wounds. In the late 19th century, the typhoid fever mortality rate in Chicago averaged 65 per 100.000 people a year. During the Spanish–American War, American troops were exposed to typhoid fever in stateside training camps and overseas, largely due to inadequate sanitation systems.

Causative Agent and Therapies

While both fevers were incredibly dangerous and contagious, typhoid fever is a bacterial infection due to Salmonella Typhi, and typhus is caused by Rickettsia bacteria. The first typhus vaccine was developed by the Polish zoologist Rudolf Weigl in the period between the two world wars and the first typhoid vaccine was developed by the British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright at the Army Medical School in Netley, Hampshire. It was first used in 1896.

Honors and Later Years

William Jenner’s early work on typhus and typhoid had already let to his appointment as professor of pathological anatomy at University College as well as assistant physician to University College Hospital. In the years to come, William Jenner would further hold the offices of Holme professor of clinical medicine, professor of medicine, full physician, and consulting physician. He was elected President of the Epidemiological Society in 1866–1868, of the Pathological Society in 1873–1875 and of the Clinical Society in 1875. He was president of the Royal College of Physicians from 1881 to 1888 where he had delivered the Goulstonian Lectures in 1853. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (F.R.S.) in 1864 and received honorary degrees from the University of Oxford, University of Cambridge, and University of Edinburgh. In 1861 he was appointed Physician Extraordinary (Q.H.P.), and in 1862 Physician in Ordinary, to Queen Victoria, and in 1863 Physician in Ordinary to the Prince of Wales; he attended both the prince consort and the prince of Wales in their attacks of typhoid fever. In 1868 he was created a baronet.

William Jenner died, at Bishops Waltham, Hants, on 11 December 1898, having then retired from practice for eight years owing to failing health. From his marriage with Adela Adey in 1858 he had several children, including his eldest son Walter, who inherited him as second baronet on his death in 1898.

‘The Great Unwashed’ – Professor Sir Richard Evans, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] William Jenner at the Royal College of Physicians

- [2] William Jenner at London’s Global University

- [3] William Jenner at Britannica

- [4] William Jenner at Wikidata

- [5] Typhoid Mary, SciHi Blog, September 23, 2015.

- [6] Charles Nicolle and the Transmission of Typhus, SciHi Blog, September 21, 2017.

- [7] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Jenner, Sir William“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 321.

- [8] Timeline of notable Deaths from Typhoid Fever, via DBpedia and Wikidata

- [9] ‘The Great Unwashed’ – Professor Sir Richard Evans, Gresham College @ youtube

- [10] John Tyndall in Lecture (19 Oct 1876) to Glasgow Science Lectures Association. Printed in ‘Address Delivered Before The British Association Assembled at Belfast‘, The Fortnightly Review (1 Nov 1876), 26 N.S., No. 119, 572.