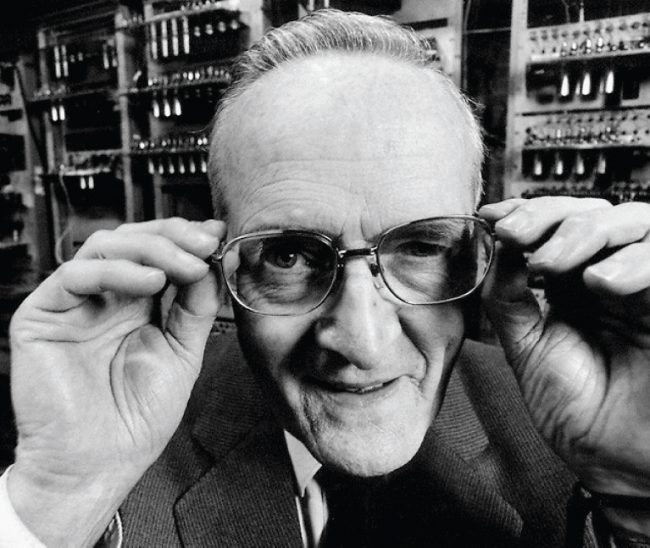

Tom Kilburn (1921 – 2001)

photo by Carolyn Djanogly, http://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2014/5/174355-tom-kilburn/abstract

On August 11, 1921, English engineer Tom Kilburn was born. Kilburn became known for having written the computer program used to test the first stored-program computer, the Small-Scale Experimental Machine, SSEM, also known as “The Baby” in 1948.

“… the most exciting time was June 1948 when the first machine worked. Without question. Nothing could ever compare with that.”

Tom Kilburn, Autumn 1992

Tom Kilburn was born in Dewsbury, Yorkshire, England and studied the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, pursuing a course compressed to two years following the outbreak of World War II. During this time, he had joined the air corps and after he had graduated in 1942, he was sent to take a six-week course in electricity, magnetism and electronics before reporting to the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) in Malvern to work on radar in Frederic Calland Williams‘ electronic problem-solving group.

From Radar to Computers

Kilburn‘s wartime work inspired his enthusiasm for some form of electronic computer. The principal technical barrier to such a development at that time was the lack of any practical means of storage for data and instructions. Storage of analog information could help solve the problem of static objects cluttering the dynamic picture on a radar screen . Storage of digital information could solve the problem holding up the development of computers worldwide. Williams eventually succeeded in storing a single bit on a cathod ray tube by 1946. In December 1946, Williams took up the chair of electrotechnics at Manchester and recruited Kilburn on secondment from Malvern.

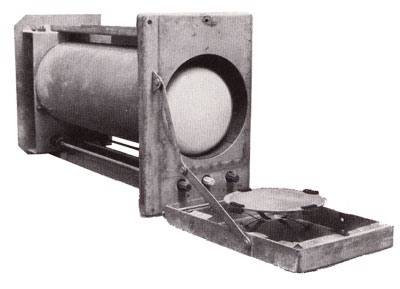

A Williams-Kilburn tube

By March 1947 Tom Kilburn had discovered a different and better method of storing information, more suited to storing a large number of bits on the same tube. By November 1947 they had succeeded in storing 2048 bits for a period of hours, having investigated a number of variations on storing a set of bits. This technology would later become known as the “Williams-Kilburn tube“. A provisional patent was already filed in 1946. The general principle behind the storage of binary information was to plant charge in one of two different ways at an array of spots on a CRT using standard techniques. The type of charge at any spot, representing a 0 or 1, could be sensed by a metal pick-up plate on the outside of the CRT screen, thus “reading” the “value” of the spot. However, the charge dissipated very quickly, so values were preserved indefinitely by continuously reading their value and resetting the charge as appropriate to the value.[2] When in Autumn 1947 the group had successfully stored 2048 digits, they had the problem of proving that the store would operate successfully inside a computer. They could only alter bits at the rate of around 1 a second, which was 100,000 times slower than the store‘s capability. In the end they decided that the simplest way to test that the CRT storage system was suitable for use in computers was to build a small computer around it.

From Small Scale to Manchester Mark I

Then Williams and Kilburn developed their storage technology and, in 1948, Kilburn put it to a practical test in constructing the Small-Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM or Manchester Machine) which became the first stored-program computer to run a program, on 21 June 1948. The first program to run was to determine the highest factor of a number. The number chosen was quite small, but within days they had built up to trying the program on 218, and the correct answer was found in 52 minutes, involving about 2.1 million instructions with about 3½ million store accesses.[3] With the success of the SSEM, a new machine was commissioned by the government that was to be more powerful and usable that the original SSEM. The design of this machine, the Manchester Mark I, was also led by Kilburn and was completed by November 1948.[1]

Williams persuaded him to stay to work on the university‘s collaborative project developing the Ferranti Mark 1, the world‘s first commercial computer. The Williams-Kilburn CRT Store was used in several models of computers including the IBM 701 and 702 computers. It was eventually superseded in new systems in about 1955 by a cheaper random access store called the “magnetic core store.”[2] Williams tubes were also used in the Soviet Strela-1 and in the Japan TAC (Tokyo Automatic Computer).. Over the next three decades, Kilburn led the development of a succession of innovative Manchester computers including Atlas and MU5.

Tom Killburn died on 17 January 2001 in Manchester, at age 79.

Ursula Martin, Alan Turing, Grace Hopper, and the history of getting things right [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Reginald Tiangha: The Manchester Machines

- [2] The Williams Tube or The Williams-Kilburn Tube, at computer50

- [3] The Manchester Small Scale Experimental Machine — “The Baby” at computer50

- [4] ENIAC – The First Computer Introduced Into Public, SciHi Blog, 13 Feb. 2013.

- [5] Howard H. Aiken and the Harvard Mark I, SciHi Blog, 09 March 2015.

- [6] Tom Kilburn at Wikidata

- [7] Ursula Martin, Alan Turing, Grace Hopper, and the history of getting things right, University of St Andrews @ youtube

- [8] Anderson, David. “Historical Reflections Tom Kilburn: A Tale of Five Computers”. Communications of the ACM. 57 (5): 35–38.

- [9] Williams, F.C.; Kilburn, T. (May 1949). “A storage system for use with binary-digital computing machines”. Proceedings of the IEE – Part II: Power Engineering. 97 (50): 183–200.

- [10] Kilburn, T. (1949). “The University of Manchester Universal High-Speed Digital Computing Machine”. Nature. 164(4173): 684–687.

- [11] Timeline of computers, via Wikidata

Shortly before he died, Tom Kilburn gave an after-dinner speech to other old boys of the school where he was educated in Dewsbury, Yorkshire (the Wheelwright Grammar School). He mentioned his work on ‘Baby’ and said that he began to write the first program to be stored on it as he waited for the train at Dewsbury station to take him to Manchester in June 1948. He was living in Dewsbury at the time.

Thanks a lot for sharing this with us!