Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881)

On December 4, 1795, Scottish philosopher, satirical writer, essayist, translator, historian, mathematician, and teacher Thomas Carlyle was born. Best known for his famous work On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History, he argued that the key role in history lies in the actions of the “Great Man“. However, Carlyle is considered one of the most important social commentators of the Victorian era.

“The weakest living creature, by concentrating his powers on a single object, can accomplish something. The strongest, by dispensing his over many, may fail to accomplish anything. The drop, by continually falling, bores its passage through the hardest rock. The hasty torrent rushes over it with hideous uproar, and leaves no trace behind.”

– Thomas Carlyle, The life of Friedrich Schiller (1825)

Thomas Carlyle – Early Years

Thomas Carlyle was born in Ecclefechan, Dumfries and Galloway, UK, the son of a wealthy tenant. He attended Edinburgh University at the age of 14 and, as he found no satisfaction in theology, devoted himself here in particular to the study of mathematics and languages, especially German language and literature. After finishing his studies he felt compelled to accept sparsely paid teaching positions first in Scotland, then in London, until a marriage, which led to a fictitious marriage, enabled him to dedicate himself entirely to literature, first on a small estate in Scotland, but since 1833 in Chelsea near London. In addition to several translations of mathematical works, he had already worked since 1823 on Sir David Brewster‘s Edinburgh Encyclopaedia and the Edinburgh Review, in particular on essays on Montesquieu, Montaigne, Nelson, the older and younger Pitt and on Goethe’s Faust.

A Preference for German Literature

Recent German literature captivated him completely, and nobody more than Carlyle contributed to passing on her knowledge to the English. In the space of a few years he published a translation of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister: William Meister’s Apprenticeship (Edinburgh 1825, 3 vols.), a biography of Schiller: Life of Schiller, an Examination of His Works (London 1825) and a selection of translations from Goethe, Fouqué, Tieck, Musäus, Jean Paul, Hoffmann and the German translation of the book “The English“. a. with critical and biographical introductions under the title German Romance (Edinb. 1827, 4 vols.) as well as a large number of smaller essays, e.g. on Werner, Novalis, Goethe’s correspondence with Schiller, Heine, the Nibelungenlied etc., which are later combined with others in the collection of his essays (5 vol.).

Goethe and Jean Paul

“He who would write heroic poems should make his whole life a heroic poem.”

– Thomas Carlyle, The Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825)

In 1826 he married Jane Welsh, whom he had known since 1821 through his friend Edward Irving. For over forty years the marriage was marked by mutual inspiration and love, but also by constant intellectual disputes. Carlyle had entered into a relationship with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe through his writings; an exchange of letters between the two was established,[1] Goethe himself took over the introduction to the German translation of the Schiller biography published in Frankfurt in 1830. Carlyle’s next larger typeface, first published in Fraser’s Magazine, bore the title Sartor resartus, or Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdroeckh; it was apparently written under the influence of Jean Paul and relentlessly turns against what he saw as the infirmities of the time.[2] Carlyle’s first extensive historical work The French Revolution: A History, London 1837, 3 vols, had a greater impact due to its brilliant and enchanting style. An essay on Chartism was published in 1839.

On Heroes and Hero Worship

“Whoso belongs only to his own age, and reverences only its gilt Popinjays or smoot-smeared Mumbojumbos, must needs die with it.”

– Thomas Carlyle, Boswell’s Life of Johnson (1832)

In the years 1837-1840 Carlyle held several lecture cycles in London, of which one series, On Heroes and Hero Worship and The Heroic in History, London 1846, was printed. From these lectures, held in front of a small but enthusiastic audience, one can clearly see the anti-rationalist, anti-utilitarian and authoritarian worldview of the Calvinist families of his Burgher secession church (a secession from the Church of Scotland) and the political system of the Romantic Carlyle, influenced by German idealism but also influenced by Calvinism. In it he lists five types of heroism: the prophet (Mohammed), the poet (Dante and Shakespeare), the priest (Luther and Knox), the writer (Johnson, Rousseau, Burns), the ruler (Cromwell and Napoleon), and emphatically advocates the right of the genius to shape the world autonomously on the basis of his intuitively gained insights into what is historically necessary. History seemed to him to be synonymous with the biography of the great men who, as Heinrich von Treitschke later put it, made it.[3]For Carlyle, chaotic events demanded what he called “heroes” to take control over the competing forces erupting within society. While not denying the importance of economic and practical explanations for events, he saw these forces as “spiritual” – the hopes and aspirations of people that took the form of ideas, and were often ossified into ideologies (“formulas” or “isms”, as he called them). In Carlyle’s view, only dynamic individuals could master events and direct these spiritual energies effectively: as soon as ideological “formulas” replaced heroic human action, society became dehumanised.

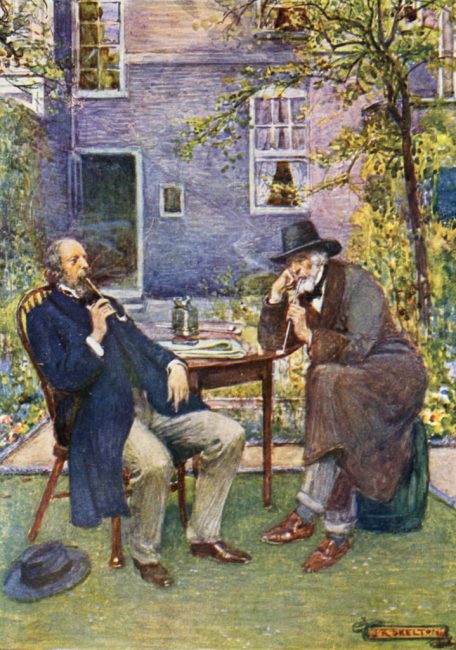

‘Carlyle and Tennyson talked and smoked together.’ by J. R. Skelton, 1920. Carlyle on Tennyson: “I do not meet, in these late decades, such company over a pipe!”

Superhuman

“Under all speech that is good for anything there lies a silence that is better. Silence is deep as Eternity; speech is shallow as Time.”

– Thomas Carlyle, Sit Walter Scott (1838)

His book Past and Present (London 1843) follows on from a diary of a monk from the 12th century and fights passionately against the hypocrisy of modern society. Friedrich Engels wrote at that time from Manchester that this typeface was the only typeface of this year worth reading from England. In 1845 Carlyle’s most important historical work appeared, his biography Cromwell (Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, London 1845, 5 vols.), which for the first time, breaking new ground, stylized the Puritan commander-in-chief and statesman into a figure of sublime greatness. The History of Frederick II, Called Frederick the Great (London 1858-1865, 6 vols.), whose mannerist language style, however, was criticized on several occasions. Here, too, there is an unmistakable tendency to stylise Frederick II as a hero figure of superhuman format.

Further Publications

“Man’s unhappiness, as I construe, comes of his greatness; it is because there is an Infinite in him, which with all his cunning he cannot quite bury under the Finite.”

– Thomas Carlyle, Sator Resartus (1833-34)

Among the most recognized biographies written in English are The Life of John Sterling (London 1851); the most recent historical works published by Carlyle are essays on the earlier history of Norway and John Knox (The early kings of Norway and an essay on the portraits of John Knox, 1875). In 1867, under the title Shooting Niagara – and After?, he fought agitation for democratic parliamentary reform; in 1871, in his Letters on the War Between Germany and France against the current in England, he strongly advocated Germany’s right against France; finally, during the Oriental turmoil, he published a polemic in favour of Russia, just as the term “the unspeakable Turk”, usually attributed to Gladstone, actually stems from him.

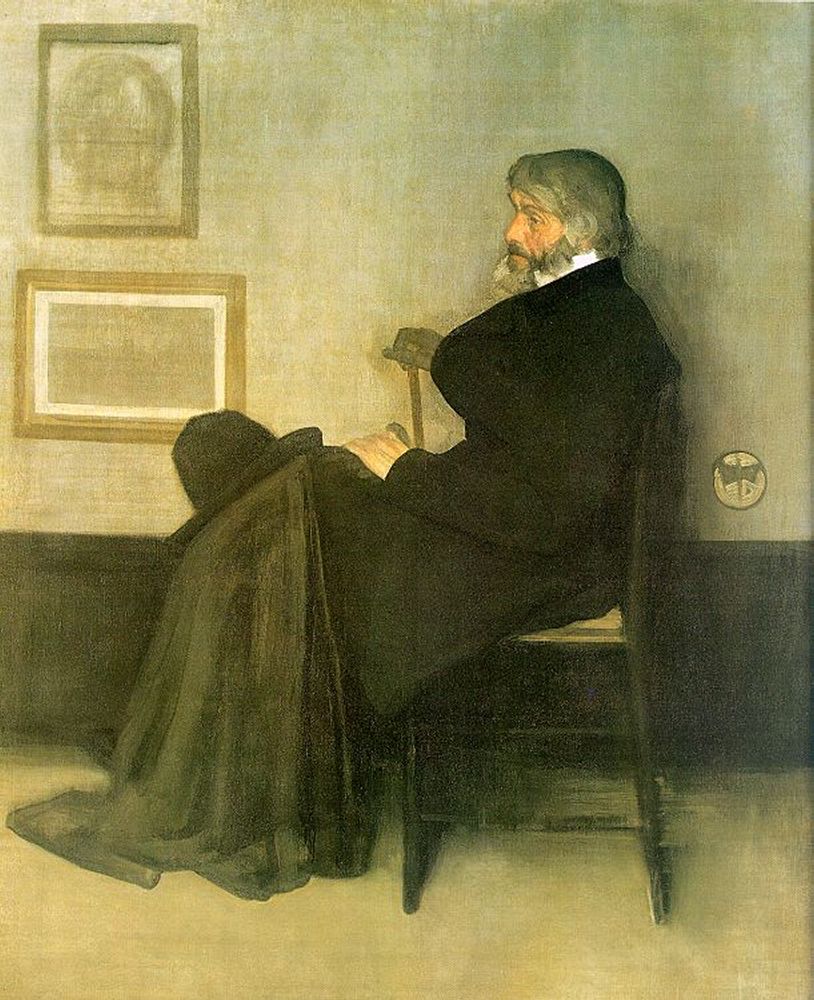

Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2: Portrait of Thomas Carlyle. James McNeill Whistler, 1872–73

Last Years

In 1865 he was elected Rector of Edinburgh University as Gladstone’s successor against Benjamin Disraeli. In 1874 Carlyle was accepted into the Prussian order “Pour le Mérite” In 1875 a gold medal was minted in England to celebrate his 80th birthday. On 3 December 1866 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 1878 he was admitted to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Carlyle died in London in 1881 as a “generally mourned luminary of the English writing world“.

Paul E. Kelly & Marylou Hill, “Thomas Carlyle Resartus: Reappraising Carlyle for Our Times”, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Life and Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, SciHi Blog

- [2] Dreams, Travelling, and Humoresques – The Literary Life of Jean Paul, SciHi Blog

- [3] The Political Thought of Heinrich von Treitschke, SciHi Blog

- [4] Frederick II – The “Wonder of the World”, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by or about Thomas Carlyle at Internet Archive

- [6] Poems by Thomas Carlyle at PoetryFoundation.org

- [7] The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily,Thomas Carlyle’s translation (1832) from the German of Goethe’s Märchen or Das Märchen

- [8] Works by or about Thomas Carlyle via Wikisource

- [9] Thomas Carlyle at Wikidata

- [10] Paul E. Kelly & Marylou Hill, “Thomas Carlyle Resartus: Reappraising Carlyle for Our Times“, Villanova Center for Liberal Education, Villanova University @ youtube

- [11] Boyle, Andrew, ed. (1913–1914). “Carlyle, Thomas”. The Everyman Encyclopædia. Everyman’s library Reference. Vol. Three. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, LTD. pp. 325–327.

- [12] Perry, Bliss (1915). Thomas Carlyle: How to Know Him. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

- [13] Shine, Hill (1953). Carlyle’s Early Reading, to 1834. Occasional Contributions. Vol. 57. Lexington: University of Kentucky Libraries.

- [14] Stephen, Leslie (1887). “Carlyle, Thomas”. In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 9. Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 111–127.

- [15] Campell, Ian (1987). “Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881)”. In Thesing, William B. (ed.). Victorian Prose Writers Before 1867. Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. 55. Detroit: Gale. pp. 46–64.

- [16] Dyer, Isaac Watson (1928). A Bibliography of Thomas Carlyle’s Writings and Ana. New York: Burt Franklin (published 1968).

- [17] Timeline for Thomas Carlyle, via Wikidata