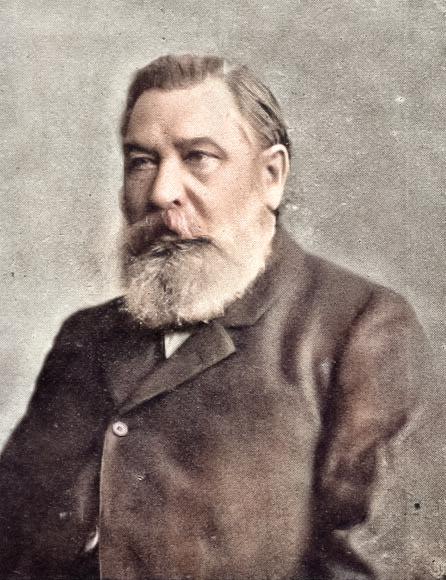

Heinrich von Treitschke (1834-1896)

On September 15, 1834, German historian and political writer Heinrich von Treitschke was born. He was one of the best known and most widely read historians and political journalists in Germany at his time. Von Treitschke was an outspoken nationalist, who favored German colonialism and opposed the British Empire. He also opposed Catholics, Poles and socialists inside Germany.

“Martial force is the basis of all political virtues; in the rich treasure of Germany’s glories the Prussian military glory is a jewel as precious, as loyally acquired as the masterpieces of our poets and our thinkers; the sacred character of the allegiance to the flag is a witness to the moral force of our people. Therefore let our Liberalism return to those ancient German convictions.”

– Heinrich von Treitschke, Statement (1869), quoted in W. W. Coole (ed.), Thus Spake Germany (London: George Routledge & Sons, 1941), p. 59.

Heinrich von Treitschke – Youth and Education

Heinrich von Treitschke came from a Saxon civil servant and officer family and was a Protestant denomination. His father was the Saxon lieutenant general Eduard Heinrich von Treitschke, who was ennobled in 1821. Von Treitschke attended the renowned Dresdner Kreuzschule (humanistic grammar school) and studied history at the Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn from 1851 to 1853, where he joined the Burschenschaft Frankonia in the winter semester 1851/52 and where he was influenced by the historian Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann, and then, at his father’s insistence, mainly state and cameral sciences at the University of Leipzig. Cameral sciences were understood to mean those sciences which provided chamber officials with the necessary knowledge for working in administration in the absolutist state. Even as a student he suffered from increasing hearing loss, which also hindered attending lectures. Because of the better library, he went to renown economist Wilhelm Roscher for his doctorate in economics at the University of Tübingen and completed his dissertation Dr. iur. (Title: Quibusnam operis vera conficiantur bona, On the productivity of labour) during a two-month stay in Freiburg im Breisgau. He then went to Heidelberg, where he spent some time in detention for a pistol duel, and then turned to Dresden and to Göttingen for the better library, where in one and a half years he wrote his habilitation, which he submitted Leipzig in 1858 (“Die Gesellschaftswissenschaft. Ein kritischer Versuch”, Social science. A critical attempt).

Publications and Teaching

During this time Treitschke was hesitant as to whether he wanted to become a poet or a journalist, tried his hand at poems and a drama. In 1858, at the invitation of Rudolf Haym, he became a member of the newly foundedPreussische Jahrbücher (Prussian Yearbooks) and attracted the attention of liberals with his essay On the Foundations of English Freedom, in which he praised the advantages of the political and legal system in England over the state arbitrariness of German relations. In 1859 he became a private lecturer in Leipzig and from 1862 also taught economics at the Agricultural Academy in Plagwitz, but increasingly turned away from economics. His lectures in Leipzig for example on Prussian history (which was unusual at a Saxon university), European and German history found already 1861 over 200 listeners. At the same time there was a quarrel with his father, the general, who had planned a different career for him and demanded that he not say anything critical to the Saxon government, which Treitschke did not want to go into.

Full Professor for History and Politics

“War is elevating, because the individual disappears before the great conception of the state…. What a perversion of morality to wish to abolish heroism among men!”

– Heinrich von Treitschke, Politics, Volume I, p. 74.

Since he saw little prospect of promotion in Leipzig despite his success as a university teacher, he spent a lot of time in Munich. In 1863 he was appointed associate professor of political science in Freiburg im Breisgau. In 1866 he took over a full professorship for history and politics at the University of Kiel. There was resistance in the faculty because of Treischke’s offensive nature and his political view of history. Also in 1866, at the outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War, his sympathies with the Kingdom of Prussia were so strong that he went to Berlin, became a Prussian subject, and was appointed editor of the Preussische Jahrbücher. His violent article, in which he demanded the annexation of the Kingdoms of Hanover and Saxony, and attacked with great bitterness the Saxon royal house, led to an estrangement from his father, a personal friend of the king. It was only equalled in its ill humour by his attacks on Bavaria in 1870. However, in 1867 he moved to the University of Heidelberg, and in 1873 he was appointed to the chair of Leopold von Ranke at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. After Ranke’s death he became his successor as official historiographer of the Prussian state.[1]

Political Career

Treitschke advocated a German monarchy and regarded monarchism as a historically grown legacy, which is why he emphatically welcomed the unification of the empire under Prussian leadership. In 1871, Treitschke became a member of the Reichstag, and from that time until his death he was one of the most prominent figures in Berlin. He was largely deaf in this period, and had an aide sit by his side to transcribe discussion into writing so he could participate. On Heinrich von Sybel‘s death Treitschke succeeded him as editor of the Historische Zeitschrift. He had outgrown his early Liberalism and become the chief panegyrist of the House of Hohenzollern. He made violent and influential attacks on all opinions and all parties which appeared in any way to be injurious to the rising power of Germany. He supported Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and his program to subdue the Socialists, Poles and Catholics (Kulturkampf) — the attempts were unsuccessful because the victims organized themselves and used universal male suffrage to their advantage in the Reichstag until Bismarck finally backed down. A strong proponent of German colonialism, Treitschke was a bitter critic of the British Empire and his condemnations resonated with some German imperialists. A growing chauvinistic Anglophobia at the end of the 19th century increasingly saw England as the strongest potential adversary of the rapidly industrialising German Empire. In the Reichstag Treitschke had originally been a member of the National Liberal Party, but in 1879 he was the first to accept the new commercial policy of Bismarck, and in his later years he joined the Moderate Conservatives, though his deafness prevented him from taking a prominent part in debate.

Antisemitism

“But today the prevailing idea is that every man should carry around a mass of notes in his head, and that is called general education.”

– Heinrich von Treitschke, Politik : Vorlesungen gehalten an der Universität zu Berlin, 1. Band, 2. Auflage. Leipzig: Hirzel, 1899, S. 182f.

Treitschke rejected the Enlightenment and liberalism’s concern for individual rights and the separation of powers in favor of an authoritarian monarchist and militarist concept of the state. He deplored the “penetration of French liberalism” (Eindringen des französichen Liberalismus) into the German nation. Treitschke was one of the few important public figures who supported antisemitic attacks which became prevalent from 1879 onwards. He accused German Jews of refusing to assimilate into German culture and society, and attacked the flow of Jewish immigrants from Russian Poland. Treitschke popularized the phrase “Die Juden sind unser Unglück!” (“The Jews are our misfortune!“), which was adopted as a motto by the Nazi publication Der Stürmer several decades later. Treitschke formulated it in his memorandum Unsere Aussichten (Our Expectations, 1879), which caused a great stir with its pointed anti-Jewish statements. He claimed that the anti-Semitic convictions thus expressed corresponded to the broad, cross-party sentiments of his contemporaries and were shared “as if from one mouth” by all, but were not openly pronounced in the press due to the “soft” and “philanthropic” zeitgeist and liberal “tabooing”. Treitschke was sharply attacked by parts of the liberal press for his statements. His attitude led to many quarrels with colleagues like Theodor Mommsen, Harry Breßlau and Johann Gustav Droysen and to a break with Jewish friends like Levin Goldschmidt.

In 1896, Heinrich von Treitschke died in Berlin at the age of 61. He is buried at the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof Berlin.

Legacy

As in his lifetime, Treitschke also had a polarizing effect after his death. On the one hand, critics also recognized the scholarship, literary vitality and rhetorical skill of his portrayal; on the other hand, as a Prussian court historian, he was often accused of taking a biased and partisan view. Representatives of the liberal historicism of his time were not always comfortable with Treitschke’s all-too-flaming and emotional partisanship for or against the protagonists of his narrative, and some questioned his suitability as a sober historian committed to the truth in the sense of Rankes. The patriotic pathos and the person-centered and national-historical narrowness of his historiography led to very pronounced judgments, apologetic consent or sharp rejection, depending on the ideological standpoint and nationality of the recipients.

Richard J. Evans, The British View of Germany: Victorian Racism [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Leopold von Ranke – The Father of the Objective Writing of History, SciHi Blog

- [2] Treitschke, Heinrich von, Treitschke, his life and works, 1914

- [3] Heinrich von Treitschke. Germany, France, Russia, & Islam (1915)

- [4] Heinrich von Treitschke. Politics (English edition 1916); Volume One; Volume Two

- [5] Davis, H. W. Carless, The political thought of Heinrich von Treitschke, 1914

- [6] Works by or about Heinrich von Treitschke at Internet Archive

- [7] Newspaper clippings about Heinrich von Treitschke in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [8] Richard J. Evans, The British View of Germany: Victorian Racism, Gresham College @ youtube

- [9] Heinrich von Treitschke at Wikidata

- [10] Timeline for Heinrich von Treitschke, via Wikidata