Joseph Justus Scaliger (1540-1609)

On January 21, 1609, French religious leader and scholar Joseph Justus Scaliger passed away. He is referred to as being one of the founders of the science of chronology, expanding the notion of classical history from Greek and ancient Roman history to include Persian, Babylonian, Jewish and ancient Egyptian history.

“All divisions in religion arise from ignorance of grammar.”

― Joseph Justus Scaliger [8]

Justus Scaliger – Early Years

Joseph Justus Scaliger was born on August 5, 1540 at Agen on the Garonne, France, the tenth child of famous Italian physician and philosopher Julius Caesar Scaliger and Andiette de Roques Lobejac. Julius Caesar Scaliger was a man of encyclopaedic knowledge and accurate observation. He employed the techniques and discoveries of Renaissance humanism to defend Aristotelianism against the new learning (i.e. Renaissance Humanism). When Joseph was twelve years old, he was sent with two younger brothers to the College of Guienne in Bordeaux, which was then under the direction of Jean Gelida, where Joseph quickly proved himself an extraordinarily precocious student. An outbreak of the plague in 1555 caused the boys to return home, and for the next few years Joseph was his father’s constant companion and amanuensis. He learned from his father to be not only a scholar, but also an acute observer, aiming at historical criticism more than at correcting texts.

Acquiring some Respectable Knowledge

In 1559 after his father’s death, he went to Paris to study Greek and Latin.[1] But after two months he found he was not in a position to profit from the lectures of the greatest Greek scholar of the time. He read Homer in twenty-one days, and then went through all the other Greek poets, orators and historians, forming a grammar for himself as he went along. From Greek, at the suggestion of Guillaume Postel, he proceeded to attack Hebrew, and then Arabic; of both he acquired a respectable knowledge [6].

An Impressive Library

In 1562, Scaliger converted to Protestantism. His most important teacher was Jean Dorat, who was able to raise Scaliger’s enthusiasm and who recommended him to Louis de Chasteigner in 1563, the young lord of La Roche-Posay, as a companion in his travels to French and German universities and to Italy to study its antiquities. After visiting a large part of Italy, the travelers moved on to England and Scotland, where Scaliger formed an unfavorable opinion of the English because of their inhuman disposition and inhospitable treatment of foreigners. In 1570 he accepted the invitation of Jacques Cujas and proceeded to Valence to study jurisprudence under the greatest living jurist with an impressive library that included five hundred manuscripts.

St Bartholomew Massacre

The massacre of St Bartholomew in August 1592 – occurring as he was about to accompany the bishop of Valence on an embassy to Poland – made Scaliger flee, together with other Huguenots, for Geneva, where he was appointed a professor in the academy. He lectured on the Organon of Aristotle and the De Finibus of Cicero to much satisfaction for the students, but not appreciating it himself.[7] He hated lecturing, and was bored with the importunities of the fanatical preachers; and in 1574 he returned to France and made his home for the next twenty years with Chastaigner. He was called to the University of Leiden in 1593, where he became known as the most erudite scholar of his time. He remained there until his death.[1]

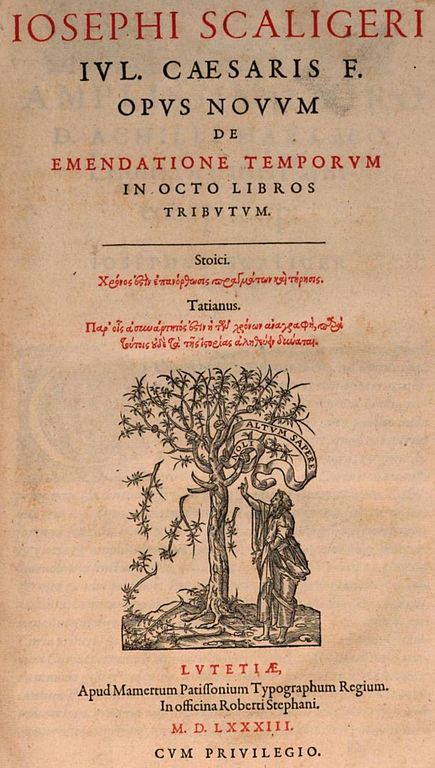

Cover Page of Joseph Justus Scaliger: De Emendatione Temporum (1583)

Scaliger’s De Emendatione Temporum – The Amendment of Time

Scaliger’s most important works are his edition of the Astronomica of the Roman poet and astrologer Manilius (1579), and his De emendatione temporum (1583), in which he revolutionized perceived ideas of ancient chronology to show that ancient history is not confined to that of the Greeks and Romans, but also comprises that of the Persians, the Babylonians and the Egyptians, hitherto neglected, and that of the Jews, hitherto treated as a thing apart. Furthermore, he showed that the historical narratives and fragments of each of these, and their several systems of chronology, must be critically compared. It was this innovation that distinguished Scaliger from contemporary scholars. Neither they nor those who immediately followed seem to have appreciated his innovation. Instead, they valued his emendatory criticism and his skill in Greek. His commentary on Manilius is really a treatise on ancient astronomy, and it forms an introduction to De emendatione temporum. In this work Scaliger investigates ancient systems of determining epochs, calendars and computations of time. Applying the work of Nicolaus Copernicus and other modern scientists, he reveals the principles behind these systems. Moreover, the publication of De Emendatione Temporum placed him at the head of all the living representatives of ancient learning.[4]

Later Life

In the remaining years of his life he expanded on his work in the De emendatione and succeeded in reconstructing the lost Chronicle of Eusebius Pamphilus, one of the most valuable ancient documents on historical synchronism, especially valuable for ancient chronology. The Chronicon of Eusebius was widely used in the medieval world to establish the dates and times of historical events. In 1606 finally, he published his Thesaurus temporum, in which he collected, restored, and arranged every chronological relic extant in Greek or Latin. Two other treatises (published in 1604 and 1616) established numismatics, the study of coins, as a new and reliable tool in historical research. Much of modern historical datings and chronology of the ancient world ultimately derives from Scaliger’s works. Moreover, Scaliger also invented the concept of the Julian Day which is still used as the standard unified scale of time for both historians and astronomers.

Graeme Dunphy, The Brill-Scaliger Lecture 2012: What is A Chronicle?, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Joseph Justus Scaliger at Britannica Online

- [2] Works by or about Joseph Justus Scaliger at Internet Archive

- [3] Joseph Justus Scaliger in Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th ed., 1902.

- [4] Josef Justus Scaliger, at classicpages.tripod.com

- [5] Joseph Justus Scaliger at Wikidata

- [6] Guillaume Postel – French Linguist and Religious Universalist, SciHi Blog

- [7] Marcus Tullius Cicero – Truly a Homo Novus, SciHi Blog

- [8] Julius Scaliger quotes at GoodReads

- [9] Joseph Justus Scaliger at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [10] The Correspondence of Joseph Justus Scaliger in EMLO

- [11] Graeme Dunphy, The Brill-Scaliger Lecture 2012: What is A Chronicle?, BrillPublishing @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of Chronologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Жозеф Скалигер и приносът му за хронологията