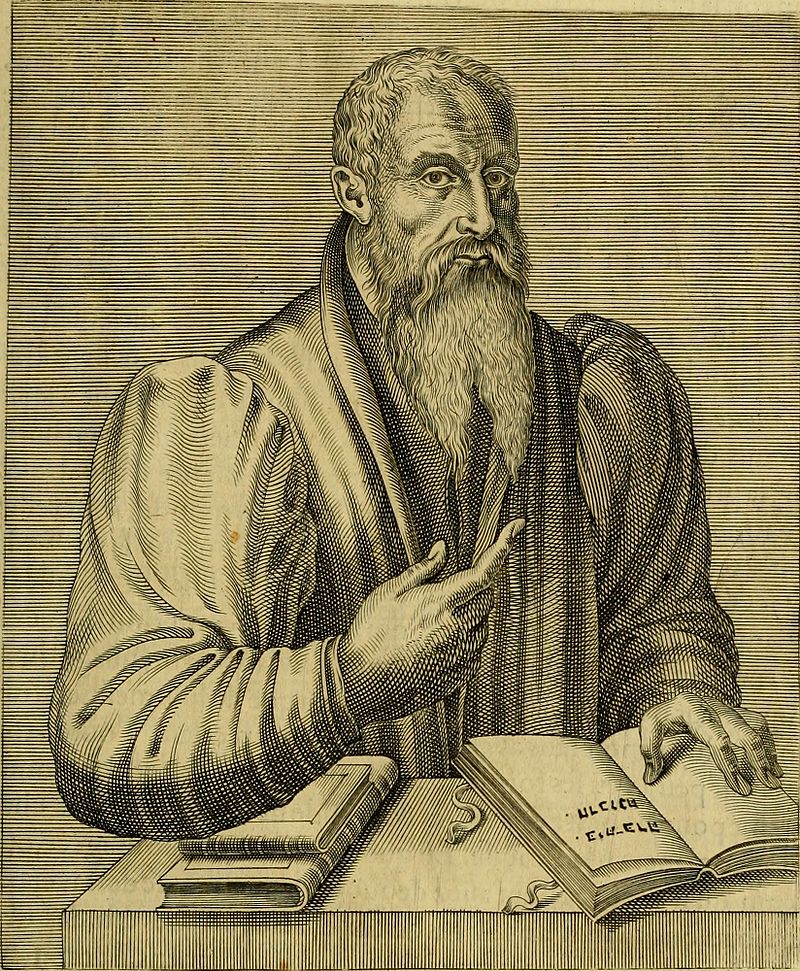

Guillaume Postel (1510-1585)

On March 25, 1510, French linguist, astronomer, Cabbalist, diplomat, professor, and religious universalist Guillaume Postel was born. A universal and cosmopolitan spirit, Postel is the most characteristic French representative of the Christian Kabbalah.

“Ibn Sina says more in one or two pages than does Galen in five or six large volumes”

– Guillaume Postel

Guillaume Postel – From Politics to Philology

Postel was adept at Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac and other Semitic languages, as well as the Classical languages of Ancient Greek and Latin and studied at the Collège Sainte-Barbe in Paris. Besides he also studied Spanish and Portuguese, while Parisian Jews taught him the basics of Hebrew. Postel soon came to the attention of the French court and in 1536, when Francis I sought a Franco-Ottoman alliance with the Ottoman Turks, he sent Postel as the official interpreter of the French embassy of Jean de La Forêt to the Turkish sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in Constantinople.

Postel was also apparently assigned to gather interesting Eastern manuscripts for the royal library, today housed in the collection of oriental manuscripts at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. In Linguarum Duodecim Characteribus Differentium Alphabetum Introductio (An Introduction to the Alphabetic Characters of Twelve Different Languages), published in 1538, Postel became the first scholar to recognize the inscriptions on Judean coins from the period of the Great Jewish Revolt as Hebrew written in the ancient “Samaritan” characters.

Concerning Harmony on Earth

From 1539 to 1543 he was teaching at the Collège des trois langues at Paris as a professor for Greek, Hebrew, and Arabic. In 1543, Postel published a criticism of Protestantism, and highlighted parallels between Islam and Protestantism in Alcorani seu legis Mahometi et Evangelistarum concordiae liber (“The book of concord between the Coran and the Gospel“). Due to intrigues and personal clumsy behavior, he was forced to leave Paris. He travelled to Rome by foot, where he joined the order of the Jesuits in 1544, where he stayed for 18 months. In 1544, in De orbis terrae concordia, (Concerning the Harmony of the Earth), Postel advocated a universalist world religion. The thesis of the book was that all Jews, Muslims and heathens could be converted to the Christian religion once all of the religions of the world were shown to have common foundations and that Christianity best represented these foundations. He believed these foundations to be the love of God, the praising of God, the love of Mankind, and the helping of Mankind. By laying open his vision of a world under French dominance with a French pope, he raised the anger of Ignatius of Loyola ,the founder of the Society of Jesus, and therefore had to leave. Nevertheless, he stayed in Rome for some time, but then continued an unsteady vagrant life as mystic, astrologer, and visionary. To Postel, the human soul is composed of intellect and emotion, which he envisages as male and female, head and heart. And the soul’s triadic unity is through the union of these two halves.

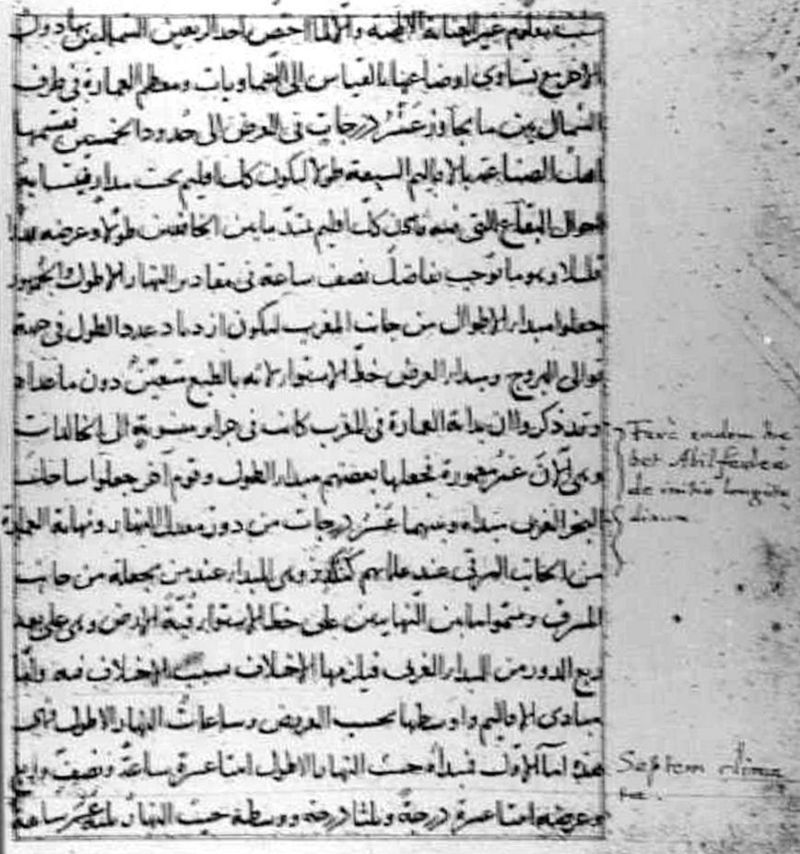

Arabic astronomical manuscript of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, annotated by Guillaume Postel

Unification of the Churches

Postel was also a relentless advocate for the unification of all Christian churches, a common concern during the period of the Reformation, and remarkably tolerant of other faiths during a time when such tolerance was unusual. This tendency led him to work with the Jesuits in Rome and then Venice, but the incompatibility of their beliefs with his prevented his full membership in their order.

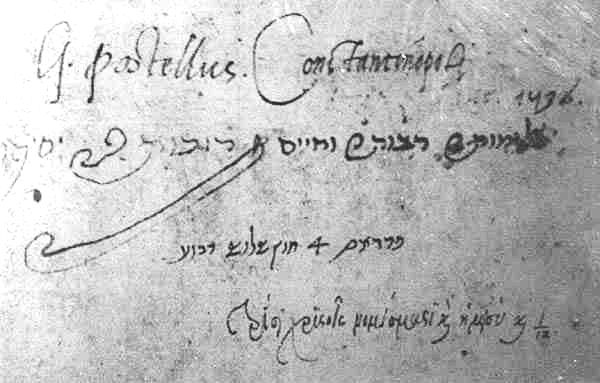

Note of Guillaume Postel on the Arabic astronomical manuscript of al-Kharaqī, Muntahā al-idrāk fī taqāsīm al-aflāk (“The Ultimate Grasp of the Divisions of Spheres”), 1536, Constantinople

Venice, Paris, and Basel

From 1547 to 1549, he stayed in Venice. Supported by his publisher Daniel Bomberg, Postel travelled to Jerusalem, Egypt, the Holy Land, and subsequently with the help of the French ambassador d’Aramont to Constantinople, from where he returned to Venice in 1550, and continued via Dijon (1552) back to Paris, where he was received mercifully. However, his benefactor Francis I had died and Postel was refused to take over a position at Collège de France. Instead, he taught at Collège des Lombards and spread his religious-political visions until this was prohibited by Henry II. He left Paris for Basel, Switzerland, where he met reformer theologians Kaspar Schwenckfeld, Sebastian Castellio and David Joris. Postel published his Apologia pro Serveto, an apology for the heretic Michael Servetus, who was burned at the stake by Johannes Calvin. Calvin reacted with an accusatory Defensio contra Servetum and Postel had to leave Basel.

Later Years

He went to Venice to work on Syriatic bible texts and continued to Vienna, where King Ferdinand I appointed him professor in 1553. When his writings were selected to be put on the index, he went to Venice to defend himself. In 1555, he was accused and condemned as heretic. Fortunately, his arguments led to a verdict of insanity and finally he was set free. Because of another of his books, he was arrested in Ravenna and put into the papal Ripetta prison in Rome, a prison for Jews and heretics. As Ripetta was charged in an uprise by the people against Pope Paul IV, Postel was able to escape in 1559. Via some detours over Basel, Venice, Augsburg, and Lyon, he returned to Paris. However, Postel did not stop preaching his visions, and in 1563 he had to retreat to the monastery St-Martin-des-Champs, where he died in 1581.

Postel’s Translations

Through his efforts at manuscript collection, translation, and publishing, he brought many Greek, Hebrew and Arabic texts into European intellectual discourse in the Late Renaissance and Early Modern periods. Among these texts are: Euclid’s Elements, in the version of the astronomer Nasīr ad-Dīn at-Tūsī, a work by the 12th-century astronomer al-Charaqī: Muntahā al-idrāk fī taqāsīm al-aflāk (“The Final Understanding of the Divisions of the Spheres“), a commentary on Ptolemy‘s Almagest, other astronomical works by at-Tūsī and other Islamic astronomers that may have influenced Copernicus’s epicycle theory, Latin translations of the Sohar, the Sefer Jetzira, and the Sefer ha-Bahir, the foundational works of the Jewish Kabbalah, published before the first Hebrew printings of these works, other Kabbalistic texts, including his own commentary on the Kabbalistic meaning of the Menorah, published in Latin in 1548 and subsequently in Hebrew.

Judith Weiss, Guillaume Postel’s Proficiency in Armaic and Hebrew, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Guillaume Postel, French philosopher, at Britannica Online

- [2] Guillaume Postel at Jewish Virtual Library

- [3] Guillaume Postel at Wikidata

- [4] Works of or about Guillaume Postel at the German Digital Library

- [5] Guillaume Postel, Cosmographicae disciplinae compendium, in suum findem, hoc est ad divinae providentiae certissimam demonstrationem conductum (Basel 1561)

- [6] Gauillaume Postel, De peregrina stella quae superiore anno primum appaere coepit (Basel 1575)

- [7] William J. Bouwsma: Concordia mundi. The career and thought of Guillaume Postel (1510-1581). Cambridge (Mass.) 1957.

- [8] Guillaume Postel at Wikidata

- [9] Judith Weiss, Guillaume Postel’s Proficiency in Armaic and Hebrew, Ben-Gurion University | אוניברסיטת בן-גוריון בנגב @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Kabbalists, via DBpedia and Wikidata