Regnier de Graaf (1641 – 1673)

On July 30, 1641, Dutch physician and anatomist Regnier de Graaf was born. De Graaf made key discoveries in reproductive biology as e.g. he discovered the follicles of the ovary (known as Graafian follicles), in which the individual egg cells are formed (1672) and also published on male reproductive organs (1668). He was also important for his studies on pancreatic juice (1663) and on the reproductive organs of mammals. He is considered one of the creators of experimental physiology. If you should have already heard of Regnier De Graaf, you for sure belong to a minority, probably you are a specialist in reproductive biology or something comparable.

Regnier De Graaf – Early Years

De Graaf was born in Schoonhoven, a city in the western Netherlands, in the province of South Holland, the son of Cornelis Maertensz de Graaf, carpenter at Schoonhoven and Catharina Reyniers van Breenen. He studied medicine in Utrecht and Leiden. There his co-students were Jan Swammerdam [2], Niels Stensen [8] and Frederik Ruysch, one of their professors was Franciscus Sylvius. As a student, De Graaf helped Johannes van Horne in the preparation of anatomical specimens. He became known for using a syringe to inject liquids and wax into blood vessels.[4] All of them were actually interested in the organs of procreation. De Graaf became a pioneer in the study of the pancreas and its secretions. In 1664, De Graaf published his work, De Succi Pancreatici Natura et Usu Exercitatio Anatomica Medica, which discussed his work on pancreatic juices, saliva, and bile. He also described the method of collecting pancreatic secretions through a temporary pancreatic fistula by introducing a cannula into the pancreatic duct in a live dog.[4] De Graaf submitted his doctoral thesis on an anatomical examination of the pancreas, and went to France where he obtained his medical degree from the University of Angers in 1665.

Research on Testicles

While in Paris, he also turned to the study of the male genitalia, which led to a publication in 1668. Back in the Netherlands in 1667, De Graaf established himself in Delft. Soon he started working for the Leiden professor Franciscus de le Boë Sylvius, who had gathered around him a number of researchers such as Niels Stensen [8] and Jan Swammerdam [2] to try to fathom the functions of the human body. Originally, he had anticipated that he would succeed Sylvius at Leiden University, but since he was a Catholic in a mainly Protestant country, he was unable to follow a university career. In 1668, De Graaf published a classic account of the testicle, which he described to be made of a collection of small tubules.[4] De Graaf also described the efferent ducts by which the spermatozoa left the testis. His authoritative 1668 work on the male regenerative organs, Tractatus de Virorum Organis Generationi Inservientibus,[1] appeared in a volume that also included his brief essay on the syringe.[4]

Female Reproductive Anatomy

But, de Graaf is most renowned for his contributions to female reproductive anatomy and physiology. His eponymous legacy are the Graafian (or ovarian) follicles. He himself pointed out that he was not the first to describe them, but described their development. From the observation of pregnancy in rabbits, he concluded that the follicle contained the oocyte, although he never observed it. The mature stage of the ovarian follicle is called the Graafian follicle in his honour, although others, including Fallopius, had noticed the follicles previously, but failed to recognize its reproductive significance. De Graaf’s contemporary Jan Swammerdam confronted him after his publication of De Mulierum Organis Generatione Inservientibu and accused him of taking credit of discoveries he and Johannes van Horne had made earlier regarding the importance of the ovary and its eggs. De Graaf issued a rebuttal but was affected by the accusation.

Untimely Death

After the early death of a son, De Graaf died in 1673 at age 32 in Delft. The reason for his death is unknown. He was, however, affected by his controversy with Swammerdam and the death of his son. It has been speculated that he may have committed suicide. His friend Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in his writings attributed his death to “choleric substances”, in those days thought to be the cause of depression.[3] A few months before his death De Graaf recommended, as a correspondent of the Royal Society in London, that attention be paid to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and his work on the improvement of the microscope.

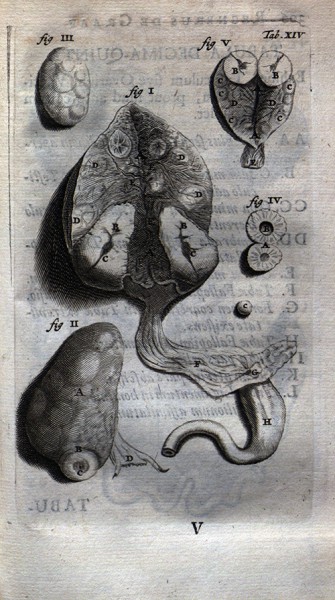

Ovaries of cows and ewes after coitus, De mulieribus in Opera 1677

The Egg as Origin of Life

After making exhaustive comparative studies of ovaries of many mammals and birds, De Graaf had concluded that the function of the female testicles was to generate ova, to nourish them, and bring them to maturity; thus, female testicles served an analogous function to ovaries in birds. He concluded that all animals and humans take their origins from an egg, which exists in the female testicles before coitus. Thus, de Graaf proposed that the female testicles be referred to as ovaries.

The G-Spot

Regnier De Graaf also described female ejaculation and referred to an erogenous zone in the vagina that he himself linked with the male prostate; this zone was later reported by German gynecologist Ernst Gräfenberg and named after him as the Gräfenberg Spot or G-Spot. Despite his contributions, De Graaf made a number of errors. Working without the aid of a microscope, he was wrongly thinking that the fluid-filled follicles were the ova themselves. He never actually consulted the ancient texts but merely repeated the accounts of others compounding their inaccuracies. Because he observed rabbits rather than humans, he assumed fertilization took place in the ovary. He believed that the seminal vesicles stored spermatozoa.

Andrey K., Ovaries (Endocrine Gland), [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] De Graaf, R (1668) De Virorum Organis Generationi Inservientibus, de Clysteribus et de Usu Siphonis in Anatomia

- [2] Jan Swammerdam – Microscopist, SciHi blog, February 12, 2016.

- [3] Antonie van Leeuwenhoek – The Father of Microbiology, SciHi blog, October 24, 2012.

- [4] Venita Jay, MD, FRCPC: The Legacy of Reinier De Graaf, A Portrait in History, Arch Pathol Lab Med—Vol 124, August 2000, pp.1115-1116

- [5] Martha Rilea, Anatomists Who Were Artists I: Reinier de Graaf, Washington University, School of Medicine in St. Louis

- [6] Regnier de Graaf at Wikidata

- [7] Nicolas Steno and the Principles of Modern Geology, SciHi Blog

- [8] De Graaf, R (1672)De mulierum organis generationi inservientibus tractatus novus : demonstrans tam homines & animalia caetera omnia, quae vivipara dicuntur, haud minus quàm ovipara ab ovo originem ducere

- [9] Andrey K., Ovaries (Endocrine Gland), Andrey K @ youtube

- [10] Houtzager HL (1981). “Reinier de Graaf“. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 12 (6): 385–7.

- [11] Ruler Han van (2003). ‘Graaf, Reinier de (1641-73)’ The Dictionary of 17th and 18th-Century Dutch Philosophers. Bristol: Thoemmes, 2003, vol. 1, 348–9.

- [12] Timeline of Dutch Anatomists, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #50 | Whewell's Ghost