Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811)

On September 22, 1741, German zoologist and botanist Peter Simon Pallas was born. Pallas was a pioneer in zoogeography by going beyond merely cataloging specimens with simple descriptions, but included observations of causal relationships between animals and their environment. He looked for hidden regularities in natural phenomena over an extreme range of habitats.

Peter Simon Pallas – Early Years

Pallas was born in Berlin, the son of Professor of Surgery Simon Pallas at the Collegium medico-chirurgicum in Berlin. He was linguistically talented and had a good command of Latin, Greek, English, French and in later years also Russian and Tatar. At the age of 13 he attended lectures at the Collegium medico-chirurgicum, where he passed the anatomical examination at 17. Here he attended lectures in mathematics and physics. In 1760 at the age of only 19 he was awarded a doctorate at the University of Leiden with a thesis entitled De infestis veventibus intra viventia (On Intestinal Worms). In this work on the parasitology of intestinal worms he assumed that the worms originate from parasite eggs. Despite several publications in zoology he was not able to find a job as a naturalist.

Research in Zoology

At his father’s request, he was to serve as a general practitioner in the Seven Years’ War, but the war ended before he was drafted. Therefore he went to Holland for three years, where he devoted himself to the order and description of natural history collections. He then settled at The Hague. Pallas published Miscellanea Zoologica (1766), his first scientific work, which included descriptions of several vertebrates new to science which he had discovered in the Dutch museum collections. It immediately attracted wide professional attention, not only because of the richness and originality of the presented empirical data, but also with its precisely stated general theoretical propositions.[3] At the age of 23 Peter Simon Pallas was elected a member of the Royal Society. In 1764 he was admitted to the Leopoldina. A planned voyage to southern Africa and the East Indies fell through when his father recalled him to Berlin. There, he began work on his Spicilegia Zoologica (1767–80).

A New System of Classification

He developed a new system for the classification of animals, based on his theory of historic development in the natural world and his idea that organisms could be represented like a family tree, showing sequential relations among the different taxonomic groups. Praised for its elegance and accuracy by George Cuvier [2], Pallas’s system was later further validated with the acceptance of the theory of evolution.

The Exploration of Russia

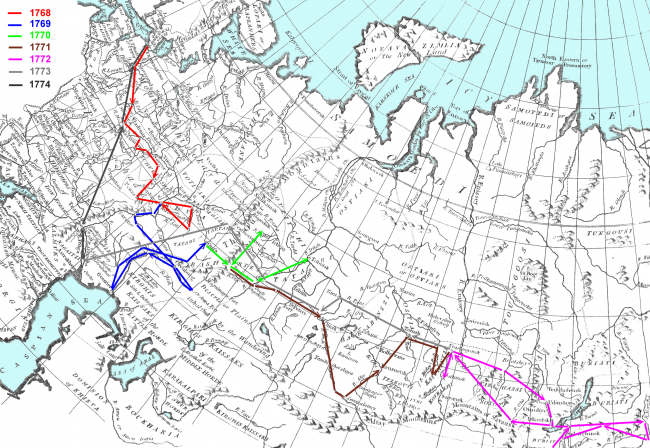

In 1767, Pallas accepted an invitation from the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences and Catherine II of Russia to come to Russia to become a professor at the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences, where he spent the next forty years, leading expeditions into much of unexplored Russia, and writing a series of works on the geology and zoology of the Asian mainland. Between 1768 and 1774, he led an expedition to central Russian provinces, Povolzhye, Urals, West Siberia, Altay, and Transbaikal, collecting natural history specimens for the academy. He explored the Caspian Sea, the Ural and Altai Mountains and the upper Amur River, reaching as far eastward as Lake Baikal. The regular reports which Pallas sent to St Petersburg were collected and published as Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs (Journey through various provinces of the Russian Empire) (1771–1776). The study was immediately translated into Russian, and then into French, Italian, and English. It covered a wide range of topics, including geology and mineralogy, reports on the native peoples and their religions, and descriptions of new plants and animals.

Peter Simon Pallas’ Russian Expeditions

Russian Flora and Fauna

Pallas settled in St Petersburg, becoming a favourite of Catherine II and teaching natural history to the Grand Dukes Alexander and Constantine. He was provided with the plants collected by other naturalists to compile the Flora Rossica (1784–1815), a Russian flora, which can be considered the first real flora of Russia, although it was never completed. At the same time, he started work on his Zoographica Rosso-Asiatica (1811–31), a zoography of Russia and Asia. The Empress bought Pallas’s large natural history collection for 2,000 rubles, 500 more than his asking price, and allowed him to keep them for life. Pallas’s studies extended beyond the limits of traditional natural history. He pondered the general processes and laws related to geology: For example, he presented a theory of the origin of mountains in intraterrestrial explosions. He also made a historical survey of land tracts discovered by the Russians in the stretches of ocean between Siberia and Alaska.[3]

Pallasites

In addition to the botanical, zoological, geological, geographic and ethnological research results, he also reports in his expedition notes on a large mass of “solid iron”, which the locals told him that it fell from the sky in 1749 near the Siberian village of Ubeisk south of Krasnoyarsk. The sensational find, initially also called “Pallas iron” and later recognized as a meteorite, played an important role in the book published in 1794 by the natural scientist Ernst F. F. Chladni,[8] who at that time was intensively engaged in the formation of such “iron masses”. Today officially called “Krasnojarsk”, this historical meteorite represents the “prototype” of the Pallasites, a subgroup of the stony iron meteorites named after P. S. Pallas.

Later Years

Between 1793 and 1794, Pallas led a second expedition to southern Russia, visiting the Crimea and the Black Sea, where he was accompanied by his daughter and his new wife, an artist, servants, and a military escort. Pallas gave his account of the journey in his P. S. Pallas Bemerkungen auf einer Reise in die Südlichen Statthalterschaften des Russischen Reichs (P. S. Pallas’ Remarks on a Trip to the Southern Governorates of the Russian Empire, 1799–1801). Catherine II gave him a large estate at Simferopol, where Pallas lived until the death of his second wife in 1810. He was then granted permission to leave Russia by Emperor Alexander, and returned to Berlin, where he died in 1811.

Legacy

By the end of his life Pallas had produced 170 publications. Most of Pallas’s studies offered no broad scientific formulations; their strength was in the richness and novelty of descriptive information. Charles Darwin referred to Pallas in four of his major works, always with the intent of adding substance to his generalizations.[3,6] Perhaps the first to publish on the relationships between different plants and animals displayed visually in the form of a tree, he was, however, a firm believer that all organisms arose at one time and that variation was in no way related to environment. [4] Together with the great mathematician Leonhard Euler,[7] Pallas was a major contributor to the elevation of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences to the level of the leading European scientific institutions. The plant genus Pallasia was named for him by Linnaeus and his name is also commemorated in the iron-based meteorite metal Pallasite and a volcano in the Kiril Islands.[4,5]

David Schwaderer, Innovation Survival: Innovation in Science [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Peter Simon Pallas at Saint-Petersburg.com

- [2] George Cuvier and the Fossils, SciHi blog, Auf, 23, 2013

- [3] VUCINICH, ALEXANDER. “Pallas, Peter-Simon.” Encyclopedia of Russian History. 2004. Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] Pallas, Peter (Pyotr) Simon von (1741-1811), at global plants

- [5] How a Cobbler became the Princeps Botanicarum – Carl Linnaeus, SciHi blog blog, May 24, 2012.

- [6] Charles Darwin and the Natural Selection, SciHi Blog

- [7] Read Euler, he is the Master of us all…, SciHi Blog

- [8] Ernst Chladni – The Father of Acoustics, SciHi Blog

- [9] Peter Simon Pallas at German Digital Library

- [10] Peter Simon Pallas at Wikidata

- [11] David Schwaderer, Innovation Survival: Innovation in Science, Google TechTalks @ youtube

- [12] Sherborn, C. Davies (1905). “The new species of birds in Vroeg’s catalogue, 1764”. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 47: 332–341.

- [13] Rainer W. Gärtner: Pallas, Peter Simon. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 20, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2001, S. 14–16

- [14] Friedrich Ratzel: Pallas, Peter Simon. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 25, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, S. 81–98.

- [15] Timeline of Explorers of Siberia, via Wikidata and DBpedia

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year, 2 Vol: #11 | Whewell's Ghost