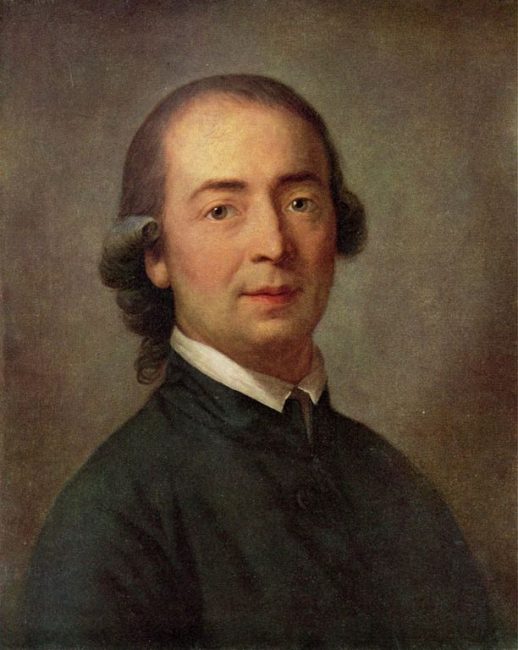

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), painting by Anton Graff, 1785, Gleimhaus Halberstadt

On August 25, 1744, German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic Johann Gottfried Herder was born. He was one of the most influential writers and thinkers of the German language in the Age of Enlightenment and, together with Christoph Martin Wieland, Johann Wolfgang Goethe [1] and Friedrich Schiller,[2] is one of the classical four stars of Weimar.

Early life and Education

Johann Gottfried Herder was born as son of the cantor and school teacher Gottfried Herder and his second wife Anna Elisabeth, née Peltz, in Mohrungen, a town with barely 2000 inhabitants in the Prussian province of East Prussia. With his Pietist parents, he was to study theology. When the younger brother Carl Friedrich died, his first poem Auf meinen ersten Todten! das Liebste, was written.

The circumstances of his parents were modest, but not so poor that a good upbringing of the children would have had to be renounced. Herder attended the city school in his hometown. He was particularly influenced by the deacon Sebastian Friedrich Trescho, also a Pietist, whose factotum he became. In return, he was allowed to use his extensive library freely. On the initiative of the Russian regimental surgeon J. C. Schwarz-Erla, Herder left Mohrungen in the summer of 1762 and went to Königsberg to become a surgeon.

Königsberg, Kant, and the Age of Enlightenment

In Königsberg, Herder soon realized that he was unsuitable for the profession of surgeon and enrolled as a student of theology at the University of Königsberg. He won a patron in the bookseller Johann Jakob Kanter, who was impressed by his anonymous work Gesang an Cyrus – Herder had secretly sent it to the Enlightenment sympathizing Czar Peter III. Kanter got him a position as an assistant teacher at the elementary school of the Collegium Fridericianum, and so Herder was able to devote himself above all to his education on a reasonably secure basis.

Only Immanuel Kant [3] was influential among the university teachers. He joined a learned circle that included Theodor Gottlieb Hippel, Johann Georg Hamann, Johann George Scheffner and Kant. Hamann and Herder criticized Kant for neglecting language as an original source of knowledge. Herder also pointed out that man “metaschematizes” already during perception, thus already anticipating insights of Gestalt psychology.

Initially Herder wrote poems and reviews for Kanters Königsbergische Zeitung. The fact that Herder was called to the cathedral school in Riga in the autumn of 1764 was convenient to him because of the threat of military service. A devastating fire inspired him shortly before his departure to write the poem Ueber die Asche Königsberg. A funeral song. Until 1769 he worked as a collaborator (assistant teacher) in Riga. It was during this period that he produced his first major works, which were literary criticism. The same year, anonymously the most important of these studies was published: Kritische Wälder, oder Betrachtungen die Wissenschaft und Kunst des Schönen betreffend (Critical forests, or considerations concerning the science and art of beauty). This was a deepening and expansion of his philosophy of language, which he based on Hamann’s statement that “poetry is the mother tongue of the human race”. According to Herder, the literary products of all nations are conditioned by the special genius of folk art and language. Here he also coined the term Zeitgeist.

Herder and Goethe meet in Strasbourg

By 1770 Herder went to Strasbourg, where he met the young Goethe. Here he drew the attention of Goethe, five years younger, to Homer, Pindar, Ossian, Shakespeare, Hamann, the folk poetry and the highly Gothic cathedral. Together they worked with Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, Rousseau, Voltaire and Paul Henri Thiry d’Holbach. This event proved to be a key juncture in the history of German literature, as Goethe was inspired by Herder’s literary criticism to develop his own style. This can be seen as the beginning of the “Sturm und Drang” movement. In 1771 Herder took a position as head pastor and court preacher at Bückeburg under Count Wilhelm von Schaumburg-Lippe. Herder passionately criticized both the orthodox attitude of theology at that time and the defensive attitude against his reformist school plans. Among other things, he polemicized against the persistent overweight of Latin in German-speaking countries.

By the mid-1770s, Goethe was a well-known author, and used his influence at the court of Weimar to secure Herder a position as General Superintendent. Herder wrote an important essay on Shakespeare and Auszug aus einem Briefwechsel über Ossian und die Lieder alter Völker (Extract from a correspondence about Ossian and the Songs of Ancient Peoples) published in 1773 in a manifesto along with contributions by Goethe and Justus Möser. Herder wrote that “A poet is the creator of the nation around him, he gives them a world to see and has their souls in his hand to lead them to that world.” To him such poetry had its greatest purity and power in nations before they became civilized, as shown in the Old Testament, the Edda, and Homer, and he tried to find such virtues in ancient German folk songs and Norse poetry and mythology.

Herder in Weimar

Herder moved to Weimar in 1776, where his outlook shifted again towards classicism. In 1774 he also argued a philosophy of history for the education of mankind against what he considered to be a dull and life-poor contemporary education. At the same time, he opened the way to a new view of history that was neither based on historical pessimism nor on an unrestricted belief in progress. History is therefore divided into epochs that build on one another organically and a diversity of cultures that exist at the same time, which possess their own laws and values and must not be judged by external standards.

Herder was one of the first to argue that language contributes to shaping the frameworks and the patterns with which each linguistic community thinks and feels. For Herder, language is ‘the organ of thought’. This has often been misinterpreted, however. Neither Herder nor the great philosopher of language, Wilhelm von Humboldt,[5] argue that language determines thought. Language is both the means and the expression of man’s creative capacity to think together with others. And in this sense, when Humboldt argues that all thinking is thinking in language, he is perpetuating the Herder tradition. But for both thinkers, culture, language, thinking, feeling, and above all the literature of individuals and the people’s folk traditions are expressions of free-spirited groups and individuals expressing themselves in space and time.

His main work Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (Philosophy of the history of mankind, 1784-1791) is based on the ideas he had already published in smaller writings. It is a summary of his knowledge about the earth and man, “whose sole purpose of existence is directed towards the formation of humanity, which all the low needs of the earth are only to serve and lead to it themselves. He presented his views on languages, customs, religion and poetry, on the nature and development of the arts and sciences, on the emergence of peoples and historical events. He regarded reason and freedom as products of the “natural” original language, religion as the highest expression of human humanity. The different natural, historical, social and psychological circumstances lead to a multi-layered differentiation of peoples, which are different but nevertheless of equal value.

Later years

Towards the end of his career, Herder endorsed the French Revolution, which earned him the enmity of many of his colleagues. At the same time, he and Goethe experienced a personal split. Another reason for his isolation in later years was due to his unpopular attacks on Kantian philosophy. In 1802 Herder was ennobled by the Elector-Prince of Bavaria, which added the prefix “von” to his last name. Johann Gottfried Herder died in Weimar in 1803 at age 59.

David Pan, Lecture 10: Johann Gottfried Herder 1, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Life and Works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, SciHi Blog

- [2] ‘Art is the Daughter of Freedom’ – Friedrich Schiller, SciHi Blog

- [3] Immanuel Kant – Philosopher of the Enlightenment, SciHi Blog

- [4] Works by or about Johann Gottfried Herder at Internet Archive

- [5] Wilhelm von Humboldt and Prussia’s Education System, SciHi Blog

- [6] International Herder Society

- [7] Johann Gottfried Herder at Wikidata

- [8] David Pan, Lecture 10: Johann Gottfried Herder 1, HUM55/EURO ST 12 WHAT IS THE ORIGIN OF LANGUAGE – Spring 2017, University of Calfornia Irvine, GROUP UCI Closed Captioning @ youtube

- [9] Headstrom, Birger R. (1929). Herder and the Theory of Evolution. The Open Court 10 (2): 596–601.

- [10] Forster, Michael N.; Herder, Johann Gottfried von (30 September 2002). Forster, Michael N (ed.). Herder: Philosophical Writings. Cambridge Core.

- [11] Clark, Robert Thomas (30 January 1955). Herder: His Life and Thought. University of California Press

- [12] Hans-Wolf Jäger: Herder, Johann Gottfried. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 8, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-428-00189-3, S. 595–603

- [13] Timeline for Johann Gottfried Herder, via Wikidata