Han s Bethe (1906 – 2005)

On July 2, 1906, German and American nuclear physicist and Nobel Laureate Hans Albrecht Bethe was born. Bethe helped to shape classical physics into quantum physics and increased the understanding of the atomic processes responsible for the properties of matter and of the forces governing the structures of atomic nuclei.

Hans Bethe Background

Hans Bethe entered the University of Frankfurt in 1924, majoring in chemistry. However, after a few semesters, he was advised to continue his studies in theoretical physics under Arnold Sommerfeld [5] at the University of Munich. Sommerfeld highly supported his talented new student through giving him copied of scientific papers and suggesting topics for Bethe’s PhD thesis. In 1929, the Bethe moved to Stuttgart in order to work at the local Technical University, where he published one of his most important scientific papers titled “The Theory of the Passage of Fast Corpuscular Rays Through Matter”. He created the famous ‘Bethe formula‘ influenced by Max Born’s [4] interpretation of the Schrödinger equation. He created a more simplified formula for collision problems using a Fourier transform and submitted his paper for his habilitation.

Bethe’s Bible

During his time at the University of Cambridge, where Bethe started in 1930, the scientists proved his great sense of humor through creating a hoax paper “On the Quantum Theory of the Temperature of Absolute Zero” along with the fellow post-doc colleagues, which caused quite a scandal in the scientific community and the responsible scientists were forced to apologize. In this period, Bethe also chose to work with Enrico Fermi [6] and managed to find the exact solutions for the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of certain one-dimensional quantum many-body models. Bethe came to Germany for one year, but was forced to move to England due to the rise of the German National Socialist Party. He was offered a position as an acting assistant professor at Cornell University in 1934, where he published a series of three articles, which summarized most of what was known on the subject of nuclear physics until that time, an account that became informally known as “Bethe’s Bible“, and remained the standard work on the subject for many years.

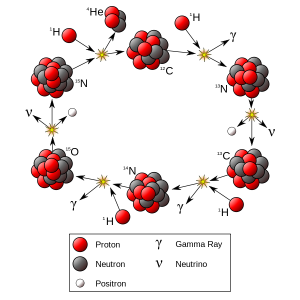

CNO Cycle

Image: Wikimedia user Borb

The Energy of the Stars

At a Conference of Theoretical Physics, Bethe heard a talk on stellar energy generation and Bengt Strömgren detailed what was known about the temperature, density and chemical composition of the Sun, and then challenged the physicists to come up with an explanation. By the end of the conference, Bethe, working in collaboration with Charles Critchfield, had come up with a series of subsequent nuclear reactions that explained how the Sun shines. However, he noticed that the processes in heavier stars was not explained and he began studying the relevant nuclear reactions and reaction cross sections, leading to his discovery of the carbon-oxygen-nitrogen cycle. These papers, co-authored with Critchfield, won a prize at New York Academy of Sciences and were subsequently published in the Physical Review. It was a breakthrough in the understanding of the stars, and would win Bethe the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1967.

Manhattan Project

During World War II, Hans Bethe was head of the Theoretical Division at the secret Los Alamos laboratory which developed the first atomic bombs. There he played a key role in calculating the critical mass of the weapons and developing the theory behind the implosion method used in both the Trinity test [7] and the “Fat Man” weapon dropped on Nagasaki in August 1945. He also played an important role in the development of the hydrogen bomb, though he had originally joined the project with the hope of proving it could not be made. Bethe later campaigned with Albert Einstein and the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists against nuclear testing and the nuclear arms race.

Later Years

After the war ended, Bethe returned to Cornell and participated in the Shelter Island Conference, the first major physics conference after the war. It was a chance for American physicists to come to together, pick up where they had left off before the war, and establish the direction of post-war research. There, Bethe was highly inspired to work on the famous Lamp shift. In 1951, together with Edwin Salpeter, he described bound states in quantum field theory with the Bethe-Salpeter equation, keeping in mind the “hydrogen atom” of the QED, the positronium (electron-positron pair), and the simplest nucleus, the deuteron (made of proton and neutron). Bethe remained scientifically active until the end of his life. From the 1970s onwards, he turned increasingly to astrophysics and used his extensive knowledge of physics, e.g. nuclear physics and the theory of shock waves – which he had already acquired in Los Alamos while studying the implosion mechanism of an atomic bomb – to investigate the theory of supernova explosions. His interest intensified when the theory of the 1987A supernova could be verified. In an influential article he pushed through the explanation of the “solar neutrino puzzle” by Russian physicists (MSW effect) (Physical Review Letters. 1986).

Hans Bethe lecture, My Relation to the Early Quantum Mechanics, November 21, 1977, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Hans Bethe at the Nobel Prize Website

- [2] Hans Bethe at Cornell University

- [3] Hans Bethe at the Atomic Archive

- [4] Max Born and the statistical interpretation of the Wave Function, SciHi Blog

- [5] Arnold Sommerfeld – Quantum Theory and Famous Students, SciHi Blog

- [6] The First Self-Sustained Nuclear Chain Reaction, SciHi Blog

- [7] Now I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds – The Trinity Test, SciHi Blog

- [8] Hans Albrecht Bethe at Wikidata

- [9] Hans Bethe lecture, My Relation to the Early Quantum Mechanics, November 21, 1977, AIP History @ youtube

- [10] Brown, Gerald E.; Lee, Sabine (2009). Hans Albrecht Bethe. Biographical Memoirs. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences.

- [11] Schweber, Silvan S. (2000). In the Shadow of the Bomb: Bethe, Oppenheimer, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- [12] Annotated bibliography for Hans Bethe from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- [13] Hans Albrecht Bethe Timeline via Wikidata