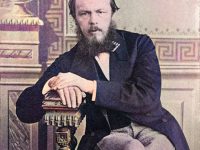

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

On December 12, 1821, French novelist Gustave Flaubert was born. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. He is known especially for his debut novel Madame Bovary, his Correspondence, and his scrupulous devotion to his style and aesthetics.

“Though she had no one to write to, she had bought herself a blotter, a writing case, a pen and envelopes; she would dust off her whatnot, look at herself in the mirror, take up a book, and then begin to daydream and let it fall to her lap. . . . She wanted to die. And she wanted to live in Paris.”

— Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary (1857)

Early Years

Gustave Flaubert grew up in Rouen (Normandy), France, as the younger son of the chief physician of the municipal hospital and, as his service villa bordered the hospital as usual at the time, experienced the suffering and dying there up close. He was considered a gifted but little disciplined student who preferred to spend his time reading and writing rather than learning. Among his childhood friends were Louis Bouilhet, who later made a name for himself as a poet, and the brother of Laure Le Poittevin, later mother of Guy de Maupassants. In the summer holidays of 1836, Flaubert fell in love with a somewhat older woman, Élisa Foucault (1810-1888), in the Norman seaside resort of Trouville-sur-Mer, who occupied him for years as a great, unattainable love and inspired his writing.

After the Baccalauréat he began to study law at the insistence of his father, but gave it up after suffering an epileptic seizure in 1843. In Paris, he was an indifferent student and found the city distasteful. He made a few acquaintances, including Victor Hugo.[1] Nevertheless, he made longer journeys during these years, the last of which led him in 1850/51 on the traces of Chateaubriand, Lamartines or Nervals in the Near East, especially Egypt. His companion was a somewhat younger friend, the writer Maxime Du Camp, who was already at the beginning of his success.

After his return, Flaubert settled in with his widowed mother and led a secluded existence as a writer’s pensioner in her house in Croisset near Rouen with her and his heir. He left this house only for occasional stays in Paris to maintain some social contacts, e.g. with fellow writers, or to meet his long-time lover (from 1846), the ten years older writer Louise Colet. With her he also discussed literary questions in many letters.

Becoming a Writer

Flaubert’s first finished work was November, a novella, which was completed already in 1842. In September 1849, Flaubert completed the first version of another novel, The Temptation of Saint Anthony. He read the novel aloud to Louis Bouilhet and Maxime Du Camp over the course of four days, not allowing them to interrupt or give any opinions. At the end of the reading, his friends told him to throw the manuscript in the fire, suggesting instead that he focus on day-to-day life rather than fantastic subjects.

Madame Bovary

In 1850 however, after returning from Egypt, Flaubert began work on Madame Bovary, which should become his first and best known literary success. The novel, which took five years to write, was serialized in the Revue de Paris in 1856. The story of Madame Bovary is based on a newspaper report from the Journal de Rouen of 1848 about the suicide of the doctor’s wife Delphine Delamare from Ry near Rouen. It tells the story of a tenant’s daughter who, after marrying a village doctor, is quickly dissatisfied with her husband, a man who loves her but who is bold, not least because she dreams of a life of passion and luxury based on novels and women’s magazines. Although she manages to take a few steps towards realizing such a life by means of two love affairs and a certain luxury consumption, she is repeatedly caught up in the triviality and narrowness of her real circumstances until she finally commits suicide, crushed by debt.

The novel immediately brought him to trial for violating morality, but Flaubert and the journal were acquitted on 7 February 1857 thanks to the wise plea of their lawyer. In the end, the trial even had a positive effect, because it helped the book version to a sales success when it was published in 1857. Less successful but even more influential in the development of the European novel was Flaubert’s L’Éducation sentimentale (1869). It tells the story of the young provincial Frédéric Moreau, who went to Paris where he hoped for a great future in politics, literature and love, but missed out on the real opportunities offered to him in favor of unreal, ideal goals, above all a long, enthusiastically unfulfilled love for a married woman who absorbed and paralyzed him.

Madame Bovary and the Éducation are regarded as epoch-making for the development of the European novel, and this because of Flaubert’s idea of no longer conceiving his protagonists as exceptional persons (as, for example, Balzac did),[2] but as completely unheroic average characters.

Further Literary Works

Flaubert’s other works are mostly less noticed today. These include in particular the historical novel Salammbô (1862), set in ancient Carthage, which Flaubert travelled to Tunisia in 1858 to prepare; the novel The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1874); the then successful collection of short stories Trois Contes (1877), including the touching story Un cœur simple, or the unfinished novel Bouvard et Pécuchet (posthumously 1881), conceived as a satire of the average bourgeoisie.

Flaubert is considered one of the best stylists of French literature and a classic of the novel. Together with Stendhal and Balzac he forms the triumvirate of the great realistic storytellers of France. Like the other two, he was not considered worthy of acceptance by the Académie française. As a writer, other than a pure stylist, Flaubert was nearly equal parts romantic and realist. Hence, members of various schools, especially realists and formalists, have traced their origins to his work.

The exactitude with which he adapts his expressions to his purpose can be seen in all parts of his work, especially in the portraits he draws of the figures in his principal romances. The degree to which Flaubert’s fame has extended since his death presents an interesting chapter of literary history in itself. In a letter to George Sand, he said that he spent his time “writing harmonious sentences and avoiding assonances“.[3] Flaubert believed and pursued the principle of “le mot juste” (“the right word”), which he regarded as the key to achieving quality in literary art. He worked in sullen solitude – sometimes a week in the completion of a page – and was never satisfied with what he had composed.

“Nothing is more humiliating than to see idiots succeed in enterprises we have failed in.”

— Gustave Flaubert, Sentimental Education (1869)

Gustave Flaubert died on 8 May 1880 in Croisset (Canteleu), Rouen, France, at age 58.

Lydia Davis, An Evening of Madame Bovary | 92Y Readings, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Writings of Victor Hugo, SciHi Blog

- [2] Honoré de Balzac and the Comédie Humaine, SciHi Blog

- [3] The Scandalous Love Affairs of George Sand, SciHi Blog

- [4] Works by or about Gustave Flaubert, via Wikisource

- [5] Site of the Centre Flaubert at Rouen (in French)

- [6] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Flaubert, Gustave“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 483–484.

- [7] Gustave Flaubert at Wikidata

- [8] Lydia Davis, An Evening of Madame Bovary | 92Y Readings, 92 Street Y @ youtube

- [9] Works by or about Gustave Flaubert at Internet Archive

- [10] Gustave Flaubert, Francis Steegmüller (1980). The Letters of Gustave Flaubert: 1830–1857. Harvard University Press.

- [11] Basch, Sophie. “Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)”. BnF Shared Heritage. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- [12] Timeline for Gustave Flaubert, via Wikidata