Victor Hugo (1802-1885)

On May 22, 1854, French poet, novelist, and dramatist of the Romantic movement Victor Hugo passed away. Hugo is considered one of the greatest and best-known French writers. Outside France, his best-known works are the novels Les Misérables, 1862, and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, 1831. In France, Hugo is known primarily for his poetry collections.

“So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilisation, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine, with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age — the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of woman by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night — are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.”

— Victor Hugo, Les Miserables, Preface

The Son of a Freethinking Republican

Victor Hugo was born in 1802 in Besançon in the eastern region of Franche-Comté, the third son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo, a French general in the Napoleonic wars, and his wife Sophie Trébuchet. Léopold Hugo was a freethinking republican who considered Napoleon a hero; by contrast, Sophie Hugo was a Catholic Royalist who was intimately involved with her possible lover General Victor Lahorie, who was executed in 1812 for plotting against Napoleon.

A Devotion to Both, King and Faith

Hugo’s childhood was a period of national political turmoil. The century prior to his birth saw the overthrow of the Bourbon Dynasty in the French Revolution, followed by the rise and fall of the First Republic. Napoleon was proclaimed Emperor and the Bourbon Monarchy was restored. The opposing political and religious views of Hugo’s parents reflected the forces that would battle for supremacy in France throughout his life. Since Hugo’s father was an officer, the family moved frequently and Hugo learned much from these travels. Weary of the constant moving required by military life, and at odds with her husband’s lack of Catholic beliefs, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold in 1803 and settled in Paris with her children. As a result, Hugo’s early work in poetry and fiction reflect her passionate devotion to both King and Faith.

From Romanticism to Naturalism

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the founder of Romanticism and France’s pre-eminent literary figure during the early 1800s.[1] Young Victor fell in love and, against his mother’s wishes, became secretly engaged to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher. Because of his close relationship with his mother, Hugo waited until after her death in 1821 to marry Adèle in 1822.

First Literary Success

In 1823, Hugo published his first novel (Han d’Islande, 1823), and his second three years later (Bug-Jargal, 1826). Between 1829 and 1840, he published five more volumes of poetry, cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time. The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo’s early work brought success and fame at an early age including a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Victor Hugo’s first mature work of fiction appeared in 1829 and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d’un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man), the story of a condemned man’s last day, in which Hugo launched a humanitarian protest against the death penalty, would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus,[5] Charles Dickens,[6] and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.[7]

Figurehead of the Romantic Movement

Hugo became the figurehead of the romantic literary movement with plays such as Cromwell (1827) and Hernani (1830). One of these plays was another verse drama, Le Roi s’amuse (1832; The King’s Fool), set in Renaissance France and depicting the frivolous love affairs of Francis I while revealing the noble character of his court jester. This play was at first banned but was later used by Giuseppe Verdi as the libretto of his opera Rigoletto.[2,8] Hugo’s novel Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris into restoring the much-neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel.

Les Misérables

“The supreme happiness of life is the conviction that we are loved.”

– Victor Hugo, Les Miserables (1862)

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but a full 17 years were needed for Les Misérables to be realised and finally published in 1862. Hugo had used the departure of prisoners for the Bagne of Toulon in one of his early stories, “La Dernier Jour d’un condamné“. Hugo was acutely aware of the quality of his novel and publication of the Miserables went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel (“Fantine“), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours and had enormous impact on French society.

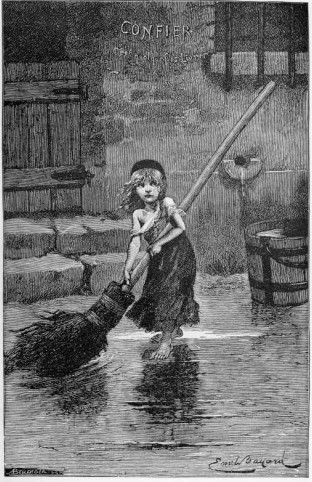

Portrait of “Cosette” by Émile Bayard, from the original edition of Les Misérables (1862)

Although received by the contemporary critics with mixed emotions, Les Misérables proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the National Assembly of France. Today, the novel remains his most enduringly popular work. It is popular worldwide and has been adapted for cinema, television, and stage shows.

Involvement in French Politics

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie Francaise in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. Thereafter he became increasingly involved in French politics as a supporter of the Republican form of government. He was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe in 1841, entering the Higher Chamber as a Pair de France, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favor of freedom of the press and of self-government for Poland.[1] Hugo decided to live in exile after Napoleon III‘s coup d’état at the end of 1851. After leaving France, Hugo lived in Brussels briefly in 1851, before moving to the Channel Islands, first to Jersey (1852–1855) and then to the smaller island of Guernsey in 1855, where he stayed until Napoleon III’s fall from power in 1870. During this exile of nearly 20 years he produced the most extensive part of all his writings and the most original.

Later Years

Although Napoleon III proclaimed a general amnesty in 1859, under which Hugo could have safely returned to France, the author stayed in exile, only returning when Napoleon III was forced from power as a result of the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. After the Siege of Paris from 1870 to 1871, Hugo lived again in Guernsey from 1872 to 1873, before finally returning to France for the remainder of his life. The remaining works Hugo completed in exile include the essay William Shakespeare (1864) and two novels: Les Travailleurs de la mer (1866; The Toilers of the Sea), dedicated to the island of Guernsey and its sailors; and L’Homme qui rit (1869; The Man Who Laughs), a curious baroque novel about the English people’s fight against feudalism in the 17th century, which takes its title from the perpetual grin of its disfigured hero. Hugo’s last novel, Quatre-vingt-treize (1874; Ninety-three), centred on the tumultuous year 1793 in France and portrayed human justice and charity against the background of the French Revolution.[2]

The End

Victor Hugo died from pneumonia on 22 May 1885, at the age of 83. Although he had requested a pauper’s funeral he was awarded a state funeral by decree of President Jules Grévy. More than two million people joined his funeral procession in Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon, where he was buried. He shares a crypt within the Panthéon with Alexandre Dumas and Émile Zola.

“To put everything in balance is good, to put everything in harmony is better.”

– Victor Hugo, Quatre-vingt-treize (Ninety-Three) (1874)

John Daniel Tolford, OUMA Lecture: Victor Hugo and French Romanticism, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Victor Hugo, at New World Encyclopaedia

- [2] Victor Hugo, French Writer, at Britannica Online

- [3] Victor Hugo in Guernsey, at Visit Guernsey

- [4] Works by Victor Hugo at Project Gutenberg

- [5] Albert Camus – the James Dean of Philosophy, SciHi Blog

- [6] Charles Dickens – Famous Writer and Critic of the Victorian Era, SciHi Blog

- [7] Fyodor Dostoyevsky – Crime and Punishment, SciHi Blog

- [8] Giuseppe Verdi – Master of the Opera, SciHi Blog

- [9] Victor Hugo at Wikidata

- [10] John Daniel Tolford, OUMA Lecture: Victor Hugo and French Romanticism, Oglethorpe University @ youtube

- [11] Timeline for Victor Hugo, via Wikidata