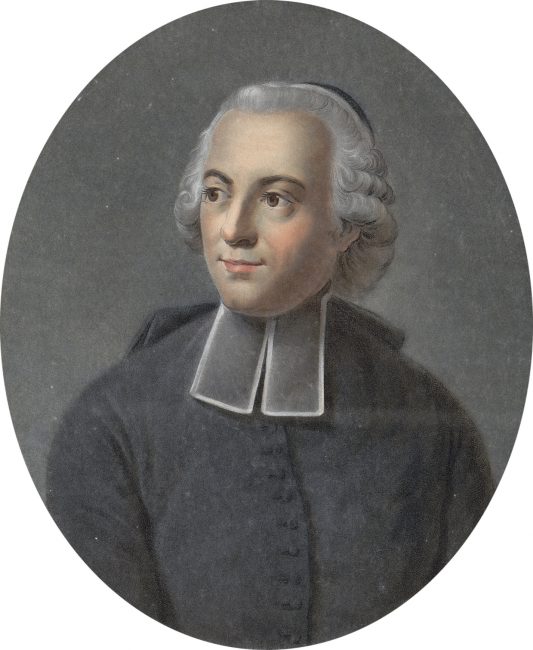

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1714-1780)

On September 30, 1714, French philosopher and epistemologist Étienne Bonnot de Condillac was born. A leading advocate in France of the ideas of John Locke de Condillac further emphasized the importance of language in logical reasoning, stressing the need for a scientifically designed language and for mathematical calculation as its basis.[4]

“The art of reasoning is nothing more than a language well arranged.”

– Étienne de Condillac, as quoted in [5]

Étienne de Condillac – Early Years

Étienne de Condillac was born at Grenoble as the youngest of three brothers to his father Gabriel Bonnot de Mably (1666-1727) and his mother, a Madame de la Coste (* 1675). Condillac” was the name of an estate purchased by his father in 1720. He is said to have had very poor eyesight and a weak physical constitution, factors that so retarded his intellectual development that as late as his twelfth year he was still unable to read. His education began only in his teens, first under the direction of a local priest, then at Lyons, later as seminarian in Paris, at Saint-Suplice and at the Sorbonne. He took holy orders in 1740 at Saint-Sulpice church in Paris and was appointed as Abbot of Mureauand, but did no pastoral work. [1]

Condillac’s Oevre

Condillac published two main philosophical works: the Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge of 1746, and the Treatise on Sensations of 1754, both of which were devoted to expositing his views on the role of experience in the development of our cognitive capacities. In his works La Logique (1780) and La Langue des calculs (1798), Condillac emphasized the importance of language in logical reasoning, stressing the need for a scientifically designed language and for mathematical calculation as its basis.[2] As a philosopher, Condillac gave systematic expression to the views of John Locke, previously made fashionable in France by Voltaire.[4,6]

Language and Writing

In Traité des systèmes (1749), Condillac distinguishes between signs that are randomly related to the object, natural signs and artificial or conditional signs (language and writing). The secret of knowledge lies in the correct use of these signs. By breaking down complicated concepts into their simplest elements, errors are avoided. The book is a vigorous criticism of those modern systems which are based upon abstract principles or upon unsound hypotheses. His polemic, which is inspired throughout by Locke, is directed against the innate ideas of the Cartesians, Malebranche‘s faculty-psychology, Leibniz’s monadism and pre-established harmony, and, above all, against the conception of substance set forth in the first part of the Ethics of Baruch Spinoza.[12]

Empirical Sensationalism

In retrospect, Condillac’s importance is both in virtue of his work as a psychologist, and his systematic establishment of Locke’s ideas in France. Like Locke, Condillac maintained an empirical sensationalism based on the principle that observations made by sense perception are the foundation for human knowledge. In the Traité des sensations, Condillac questioned Locke’s doctrine that the senses provide intuitive knowledge.Condillac traces all the functions of the soul (feelings, desires, acts of the will) back to the sensations that underlie them. The sensation itself and the psychic experience were intellectualized by him. The mind sees more than the eye, writes Condillac. He doubted, for example, that the human eye makes naturally correct judgments about the shapes, sizes, positions, and distances of objects. Examining the knowledge gained by each sense separately, he concluded that all human knowledge is transformed sensation, to the exclusion of any other principle, such as Locke’s additional principle of reflection.[2]

According to Condillac, all sensation is affective, that is, causes pain or pleasure. Sensations, consequently, are the source of all active faculties. Need, for example, is the result of the privation of some object whose presence is demanded either by nature of habit. Need, subsequently, directs all energy towards this missing object. This directionality, Condillac claimed, is what we call desire. Will is absolute desire, made vigilant by hope.

Philosophical Circles

In Paris Condillac spent some years living the life of a man of letters in Paris and was involved with the circle of Denis Diderot,[10] the philosopher who was co-contributor to the Encyclopédie.[9] He developed a friendship with Jean Jacques Rousseau,[11] which lasted in some measure to the end of his life. Together with his brother Gabriel, who became the well-known political writer known as Abbé de Mably, Condillac introduced Rousseau to an intellectual circle. Condillac’s relations with unorthodox philosophers did not injure his career. He had already published several works when the French court sent him to Parma to educate the orphan duke Prince Ferdinand of Parma, then a child of seven years. Condillac’s Histoire ancienne and Histoire moderne (1758–1767) demonstrated how the experience and observation of the past aided man. History was not a mere retelling of the past, but a source of information and inspiration as well. Reason and critical thinking can improve man’s lot and destroy superstition and fanaticism. History thus served as a moral, political, and philosophical textbook which taught man to live better. Thus the two histories present the basic program of the Enlightenment in crystallized form.

Later Years

In 1768, on his return from Italy, Condillac was elected to the Académie française. Contrary to the popular idea that he attended only one meeting, he was a frequent attendee until two years before his death. Near the end of his life, Condillac turned his attention to politics and economics. His economic views, which were presented in Le Commerce et le gouvernement, were based on the notion that value depends not on labour but rather on utility. The need for something useful, he argued, gives rise to value, while prices result from the exchange of valued items.[2] Finding the irreligious climate of Parisian intellectual society offensive, he retired to spend his last years at Flux, near Beaugency on the Loire River. He died there on 3 August 1780.

Justin Champion, Why the Enlightenment still matters today, [14]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Falkenstein, Lorne; Grandi, Giovanni. “Étienne Bonnot de Condillac”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [2] Étienne de Condillac at Encyclopedia Britannica

- [3] Étienne de Condillac at The European Grad School

- [4] John Locke and the Importance of the Social Contract, SciHi Blog

- [5] Antoine Lavoisier, Elements of Chemistry (trans. Robert Kerr, 1790), Preface, p. xiv.

- [6] Voltaire – Libertarian and Philosopher, SciHi Blog

- [7] Sturt, Henry (1911). “Condillac, Étienne Bonnot de“. In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 849–851.

- [8] Knight, Isabel F. (1968). The Geometric Spirit: The Abbe de Condillac and the French Enlightenment. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- [9] Jean Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert and the Great Encyclopedy, SciHi Blog

- [10] Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, SciHi Blog

- [11] “Man was born free, and he is everywhere in chains” – Jean-Jacques Rousseau, SciHi Blog

- [12] You are either a Spinozist or not a Philosopher at all, SciHi Blog

- [13] Étienne de Condillac at Wikidata

- [14] Justin Champion, Why the Enlightenment still matters today, Gresham College @ youtube

- [15] Timeline of Ontologists, via Wikidata and DBpedia