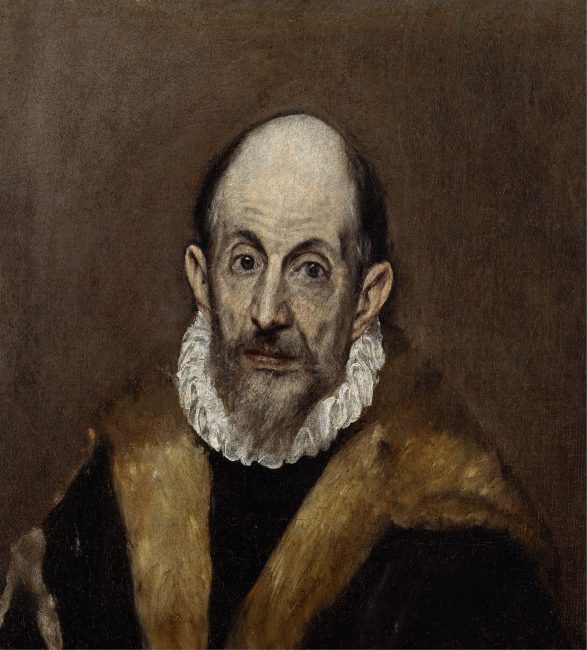

El Greco (1541 – 1614) Portrait of a Man (presumed self-portrait of El Greco, c. 1595–1600) in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

On April 7, 1614, Greek painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance Doménikos Theotokópoulos, widely known as El Greco, passed away. A major master of Spanish Mannerism and the fading Renaissance, he painted mainly pictures with religious themes and portraits. His painting developed away from naturalism toward an individual style, as he attempted to find a new expression for spiritual phenomena, and in his later work increasingly referred back to his origins as an icon painter. El Greco is regarded as a precursor of both Expressionism and Cubism.

“I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art.”

— El Greco, from notes of the painter in one of his commentaries, quoted in [1]

From Domenikos Theotokopoulos…

Domenikos Theotokopoulos, called ‘El Greco’, was born in 1541 in Candia, the then capital of the island of Crete, now Heraklion. At the time of his birth, Crete belonged to the Republic of Venice, for which his father Georgios Theotokopoulos worked as a state tax collector. No information has survived about El Greco’s mother or his first Greek wife. Nothing is known about El Greco’s childhood either. There was a school of icon painting on Crete that combined Orthodox tradition with Western influences brought to the island via prints from Venice. In one of these workshops El Greco received his artistic education in the tradition of the Cretan school. In 1563 he was described in a document as a master of icon painting. The earliest work known today and signed by El Greco with his civil name is a motif of the Dormition of Mary in 1567.

…to El Greco

In 1568 El Greco was present in Venice, documented by a letter. He stayed in Venice for three years and painted many pictures there. The main thing they have in common is that El Greco approached the local artists such as Jacopo Bassano, Jacopo Tintoretto and Titian.[2] In place of the gold ground, El Greco now used perspective space, drawing on architectural tracts such as that of Sebastiano Serlio. He also abandoned tempera painting, turned to oil painting, which had been widespread in the West since Jan van Eyck,[13] and began to use canvases as picture supports. In 1570, the miniature painter Giulio Clovio pointed out to his patron Alessandro Farnese in Rome a self-portrait of El Greco, now lost, that would have amazed Roman artists, and recommended that the artist be admitted to the Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola. He recommended El Greco to his patron as a pupil of Titian. He also sought recognition in other genres, but in Rome he had to face competition from many high-ranking painters who worked in the tradition of Michelangelo.[3] In order to set himself apart and to show off his foreignness as a strength, El Greco referred to Titian.[ This is also the context of the anecdote, according to which El Greco offered the Pope to paint over Michelangelo’s criticized Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel.[4] As a result, he had to leave the city due to the criticism of the Roman painters. El Greco was dismissed from the House of Farnese and decided to go his own way in Rome. On September 18, 1572, he paid the two scudi admission fee and thus joined the Roman Guild of St. Luke under the name Dominico Greco.

First Years in Spain

El Greco’s presence in Spain is attested for October 1576 – how he got there is not known. Through the mediation of Diego de Castilla, his friend’s father and dean of the cathedral, he created an altar for the Cistercian abbey of Santo Domingo de Silos in Toledo. He not only designed the pictorial program, which suited the funeral chapel with the bodily assumption of Mary into heaven as the central image, but also designed the architecture of the retable, its sculptural decoration and the tabernacle. Also through the mediation of Diego de Castilla, but who in this case was not solely responsible, El Greco painted Christ is stripped of his clothes for Toledo Cathedral.

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586–1588), now El Greco’s best known work, illustrates a popular local legend. An exceptionally large painting, it is clearly divided into two zones: the heavenly above and the terrestrial below, brought together compositionally.

Transition from Naturalism

Between 1577 and 1579 El Greco painted the Adoration of the Name of Jesus, with which he wanted to recommend himself to King Philip II. In this painting he brought the king directly as a figure. Between 1580 and 1582, El Greco painted The Martyrdom of St. Maurice as a trial painting for the church of the Escorial,[5] in order to gain a foothold at court in Madrid after his successes in Toledo. In this situation, El Greco made a stylistic change from naturalism to painting in which he sought creative expression for spiritualism. With the construction of the Escorial, the king pursued the intention of implementing the ideas of the Council of Trent, which he had helped to shape. To this end, he actually wanted to entrust Juan Fernández de Navarrete with the design of all the altars. Navarrete died, however, so new painters had to be sought. Perhaps because of the first painting with which El Greco wanted to recommend himself at court, the Adoration of the Name of Jesus, the king considered the Greek as a possible replacement. El Greco delivered an artistic painting, but it contradicted the ideals of the Council in its turn against naturalism. Instead of the planned display site on the altar of the Escorial Church, the painting was hung in a less prominent place in the church. Philip II commissioned Romulo Cincinato to make a painting on the same theme. The latter based his work on El Greco’s composition, but changed its emphasis. Overall, this approach contradicts the anecdotes and reports about the strong influence of the Inquisition on art production in Spain. It was precisely with the support of open-minded church circles that the Greek El Greco was able to develop Baroque pictorial ideas in Spain that did not become established elsewhere until the 17th century.

View of Toledo (c. 1596–1600, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is one of the two surviving landscapes of Toledo painted by El Greco.

Later Years and Death

After failing at court, the painter sought new patrons among the clergy of Toledo. His trial painting was a portrait of a cardinal, Fernando Niño de Guevara, who was Grand Inquisitor in Toledo around 1600. The rejection in Madrid strengthened El Greco’s attachment to Toledo. In 1586, the priest of his own parish commissioned him to paint The Burial of the Count of Orgaz. In 1597, El Greco received a major commission to decorate the Capilla de San José in Toledo, his most important commission in Toledo after Santo Domingo el Antiguo. Despite numerous well-paid commissions, El Greco often found himself in economic difficulties because he maintained a very upscale lifestyle. Thus, he occasionally employed musicians to entertain him during meals. The following year, El Greco was commissioned by Pedro Salazar de Mendoza to paint three altarpieces for the Hospital de Tavera. However, this work remained unfinished. El Greco died on April 7, 1614. At the time of his death, El Greco was heavily in debt. He left no will, which was unusual at the time. Jorge Manuel Greco drew up an inventory of his father’s possessions, which included 143 mostly finished paintings, including three versions of Laocoon, 15 plaster models, 30 clay models, 150 drawings, 30 plans, 200 prints, and over 100 books.

The Opening of the Fifth Seal (1608–1614, New York, Metropolitan Museum) has been suggested to be the prime source of inspiration for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Harbinger of Modernity

The reception of El Greco varied greatly over time. He was not promoted by the nobility, but relied mainly on intellectuals, clergy, humanists and other artists. After his death, his art received little appreciation and was sometimes ignored. His slow rediscovery began in the 19th century, and around 1900 El Greco had his breakthrough. This was carried less by art history, but by writers, art critics and the artistic avant-garde. The primacy of imagination and intuition over the subjective character of creation was a fundamental principle of El Greco’s style. El Greco discarded classicist criteria such as measure and proportion. He believed that grace is the supreme quest of art, but the painter achieves grace only by managing to solve the most complex problems with ease. The visionary nature of El Greco’s art can also be discovered in the painting The Opening of the Fifth Seal, which has as its subject the vision of John the Evangelist and was a fragment of a late altarpiece project. Pablo Picasso [6] had experienced this rediscovery of El Greco himself in Barcelona and Madrid. In his first important phase of work, the Blue Period, his painting The Burial of Casagemas referred to The Burial of Count Orgaz. One of Picasso’s drawings was even titled Yo El Greco (“I El Greco“). In the Pink Period, in his painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, which was received as a scandal, he took up motifs from The Opening of the Fifth Seal.

Ellen Prokop: “The Father of Modern Painting? El Greco’s Critical Fortunes”, [14]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Marias Fernando, Bustamante García Agustín (1981). Las Ideas Artísticas de El Greco (in Spanish). Cátedra.

- [2] Titian – the Sun Amidst Small Stars, SciHi Blog

- [3] Michelangelo Buonarotti – the Renaissance Artist, SciHi Blog

- [4] Michelangelo’s Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, SciHi Blog

- [5] El Escorial – The World’s largest Renaissance Building, SciHi Blog

- [6] Pablo Picasso – A Giant in Art, SciHi Blog

- [7] El Greco – The Complete Works at the El Greco Foundation

- [8] “El Greco”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of European Paintings.

- [9] Works by or about El Greco at the German Digital Library

- [10] El Greco at Wikidata

- [11] Timeline for El Greco, via Wikidata

- [13] Jan van Eyck – the King among the Painters, SciHi Blog

- [14] Ellen Prokop: “The Father of Modern Painting? El Greco’s Critical Fortunes“, at The Frick Collection, @ youtube