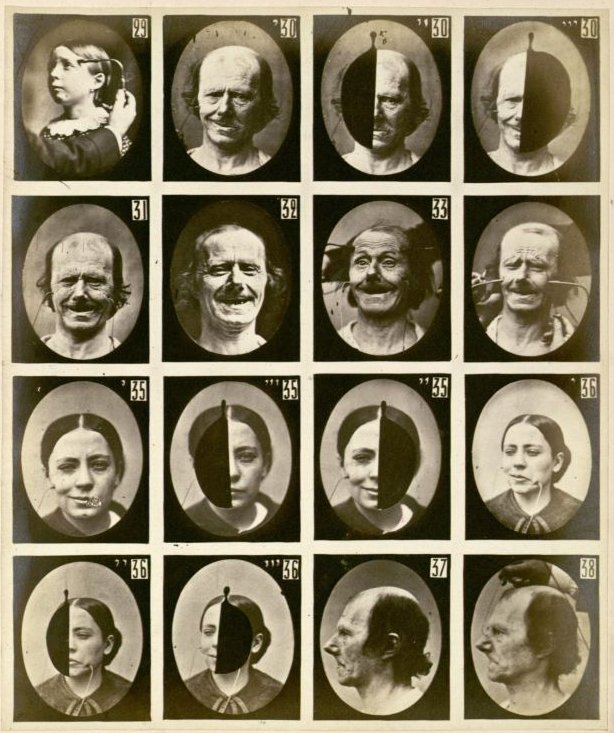

Duchenne de Boulogne, Facial expressions triggered by electric stimulation

On September 17, 1806, French neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne was born. Duchenne de Boulogne revived Galvani‘s research and greatly advanced the science of electrophysiology.[3] The era of modern neurology developed from Duchenne‘s understanding of neural pathways and his diagnostic innovations including deep tissue biopsy, nerve conduction tests (NCS), and clinical photography. He was first to describe several nervous and muscular disorders and, in developing medical treatment for them, created electrodiagnosis and electrotherapy.

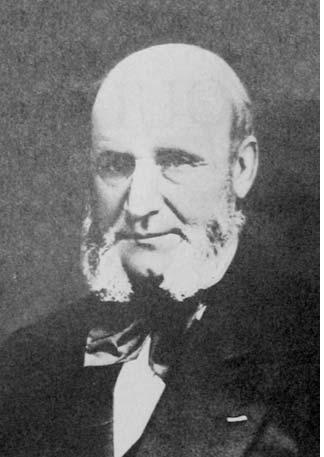

Duchenne de Boulogne (1806-1877)

Duchenne de Boulogne – Early Years

Guillaume Duchenne was born in Boulogne-sur-Mer into a family of sailors. In opposition to his father’s wishes that he become a sailor, and driven by a fascination with science, Duchenne enrolled at the University of Douai where he received his Baccalauréat at the age of 19. He then trained under a number of distinguished Paris physicians including René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781–1826) and Baron Guillaume Dupuytren (1777–1835) before returning to Boulogne and setting up in practice there.

Therapeutic Electropuncture

During the 1830s, Duchenne started to experiment with the so called therapeutic “électropuncture”, a method by which electric shock was administered beneath the skin with sharp electrodes to stimulate the muscles. During the 1840s, Duchenne moved to Paris and continued his research there. During that period, Duchenne developed a technique of muscle stimulation that used faradic shock on the surface of the skin, which he called “électrisation localisée”. He was able to publish these experiments in his work, On Localized Electrization and its Application to Pathology and Therapy. One of Duchenne’s most relevant works, The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy, was highly discussed by temporary scientists. Duchenne summarized his results of nearly 20 years of study in his influential work Physiology of Movements.

Physiological Experiments

In 1842,Duchenne moved to Paris where he spent the rest of his life developing clinical applications of electricity. A doctor without official hospital status, he impressed by the rigour of his experiences, which earned him the title of “master” from Jean-Martin Charcot.[4] Duchenne was a pioneer in the use of electricity as an instrument for physiological experiments. The use of alternating current allowed it to precisely stimulate only one muscle beam at a time. Thanks to this technique, he described several diseases and localized their origin, as was the case with a form of muscular atrophy that now bears his name, (Duchenne muscular dystrophy), and tabes. He also worked on polio, individualizing for the first time each of the facial muscles and inaugurating the biopsy technique by inventing an instrument to take tissue samples inside the body.

Demonstration of the mechanics of facial expression. Duchenne and an assistant faradize the mimetic muscles of “The Old Man.”

Duchenne defines the fundamental expressive gestures of the human face and associates each with a specific facial muscle or muscle group. He identifies thirteen primary emotions the expression of which is controlled by one or two muscles. He also isolates the precise contractions that result in each expression and separates them into two categories: partial and combined. To stimulate the facial muscles and capture these “idealized” expressions of his patients, Duchenne applied faradic shock through electrified metal probes pressed upon the surface of the various muscles of the face.

Electro-Therapeutics

Duchenne de Boulogne became known as one of the developers of electro-physiology and electro-therapeutics. He was able to show that smiles resulting from true happiness not only utilize the muscles of the mouth but also those of the eyes: such “genuine” smiles are known as Duchenne smiles in his honor. Duchenne’s great originality also lies in the artistic perspective of his work. Hesitant to attend the École des beaux arts de Paris, Duchenne drew facial expressions perfectly well. As a photographer, he meticulously recorded all possible facial expressions using a man with paralyzed features as a model, or guinea pig. It was with the help of electricity that the expressions were obtained.

Jeam-Martin Charcot and the Hysterics

Duchenne’s most famous student was Jean-Martin Charcot,[4] who became director of the insane asylum at the Salpêtrière in 1862. He adopted Duchenne’s procedure of photographic experiments and also believed that it was possible to attain the “truth” through direct observation. He even named an examination room at the asylum after his teacher. Like Duchenne, Charcot sought to chart the gestures and expressions of his patients, believing them to be subject to absolute, mechanistic laws. However, unlike Duchenne, who restricted his experiments to the realm of the sane, Charcot was interested almost exclusively in photographing the expressions of traumatized patients – the “hysterics”.

Despite his unorthodox procedures, and his often uneasy relations with the senior medical staff with whom he worked, Duchenne’s single-mindedness obtained him an international standing as a neurologist and researcher. Duchenne died in 1875 at age 68, after several years of illness. He was never elected to the French Academy of Sciences.

Lecture 3: Cell Electrophysiology, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Electro-Physiognomy

- [2] Duchenne de Boulogne at Britannica Online

- [3] Luigi Galvani’s Discoveries in Bioelectricity, SciHi Blog

- [4] Jean-Martin Charcot – A Pioneer in Neurology, SciHi Blog

- [5] Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne bei Google Arts & Culture

- [6] Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne at Wikidata

- [7] Lecture 3: Cell Electrophysiology, ThomKlepach @ youtube

- [8] Duchenne de Boulogne, G.-B.; Cuthbertson, Andrew R. (1990). The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression. Cambridge UK; New York; etc.: Cambridge University Press.

- [9] Duchenne, Guillaume-Benjamin; Tibbets, Herbert (1871). A treatise on localized electrization, and its applications to pathology and therapeutics. London: Hardwicke.

- [10] Parent, André (August 2005). “Duchenne De Boulogne: a pioneer in neurology and medical photography”. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 32 (3): 369–77.

- [11] Timeline for Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne, via Wikidata