Charles Lyell (1797 – 1875)

On November 14, 1797, Charles Lyell, British lawyer and the foremost geologist of his day, was born. Lyell was a close friend to Charles Darwin and is best known as the author of Principles of Geology, which popularized James Hutton‘s concepts of uniformitarianism – the idea that the earth was shaped by the same processes still in operation today.

“The form of a coast, the configuration of the interior of a country, the existence and extent of lakes, valleys, and mountains, can often be traced to the former prevalence of earthquakes and volcanoes in regions which have long been undisturbed. To these remote convulsions the present fertility of some districts the sterile character of others, the elevation of land above the sea, the climate, and various peculiarities, may be distinctly referred.”

– Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology

Background and Career

Charles Lyell was born in a wealthy family at the family’s estate house, Kinnordy House, near Kirriemuir in Forfarshire. He grew up in Scotland and entered his father’s footsteps through becoming a lawyer as well as showing a great interest in nature. Since the family spent most of their time in forests and on farms, there was much to discover. Lyell entered Exeter College in Oxford in 1816 and was already elected joint secretary of the Geological Society a few years after, which caused him to completely focus on geology. Lyell was lucky to share his interests in studying Earth’s conditions with the woman he loved, so he took her on a geological trip for their honeymoon.

Everything seemed to turn out great for Lyell, especially in sense of his career. In his mid-30’s, Lyell was a well known and highly accepted geologist. During this time, he held a post as Professor of Geology in London and published his Principles of Geology, which again increased his great reputation as a scientist. In his book, he leaned on David Hume‘s theory [6] that “all inferences from experience suppose … that the future will resemble the past” and James Hutton‘s theory of uniformitarianism,[5] which he greatly supported and therefore caused it to be widely accepted by society.

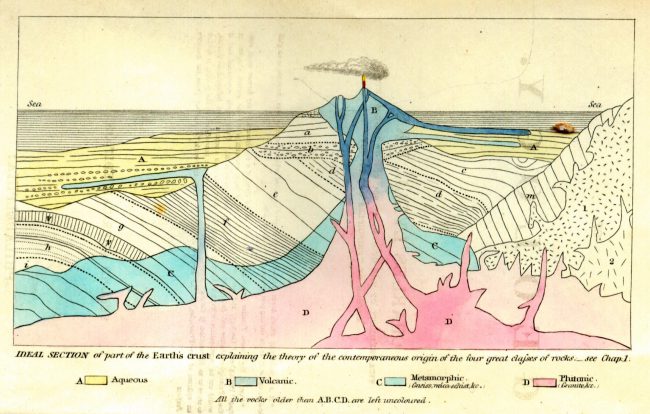

The frontispiece from Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (second American edition, 1857), showing the origins of different rock types.

Elements of Geology

“When we study history we obtain a more profound insight into human nature by instituting a comparison between the present and former states of society.”

– Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology (1832), Vol. 1

Lyell travelled through Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Scandinavia and North America to examine his principles. On his first journey through North America in 1841 and 1842, he visited the cliffs of Joggins in Nova Scotia, Canada, where he was guided by Abraham Gesner, then chief geologist of New Brunswick. In 1852, on his second trip to North America, Lyell visited Joggins again, this time with John William Dawson. He published his experiences and impressions together with geological descriptions in Travels in North America and in A second visit to the United States of North America.

Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin

“Mr. Darwin labours to show, and with no small success, that all true classification in zoology and botany is, in fact, genealogical, and that community of descent is the hidden bond which naturalists have been unconsciously seeking, while they often imagined that they were looking for some unknown plan of creation.”

– Charles Lyell, The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man (1863)

Lyell, who saw himself as “the spiritual saviour of geology, freeing the science from the old dispensation of Moses“, influenced many scientists of his period, but the most special scientific relationship and private friendship developed between Lyell and Charles Darwin.[7] Darwin heard of Lyell’s Principles and while studying them, he made several observations in South America which he exchanged with Lyell in a fruitful scientific correspondence. Their friendship grew even though Lyell rejected the theory of evolution that Darwin deeply believed in. It took nine editions of Lyells Principles and years of discussion with Darwin to finally grant Darwin’s theories on evolution some respect and at the end, he even supported Darwin to publish his masterpiece ‘On the Origin of Species‘.

Later Years

Lyell proved that the coasts of Sweden had been elevated for several centuries and gave a plausible explanation for the formation of the Niagara Gorge: the retrograde erosion at the Niagara Falls. In his latest work, Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, Lyell showed that humans must have existed for much longer than had previously been believed. Lyell died on 22 February 1875 in London and received a funeral at Westminster Abbey.

Through his scientific achievements, the geological surveys, works on geological dynamics, and his great influence to Charles Darwin, Lyell counts as one of the most important scientists of the Victorian Era, wherefore he was knighted, made a baronet, and honored numerous times like having a Lunar and Martian crater named after him.

People of Science with Brian Cox – Richard Fortey on Charles Lyell [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Lyell on Victorian Web

- [2] Uniformitarianism at Berkeley

- [3] Lyell at Famous Scientists

- [4] Lyell at Wikidata

- [5] James Hutton – the Father of Modern Geology, SciHi Blog

- [6] You Don’t Exist. – says David Hume, SciHi Blog

- [7] Charles Darwin and the Natural Selection, SciHi Blog

- [8] People of Science with Brian Cox – Richard Fortey on Charles Lyell, The Royal Society @ youtube

- [9] Works by or about Charles Lyell at Internet Archive

- [10] Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology (7th edition, 1847) from Linda Hall Library

- [11] Adams, Frank Dawson (1938). The birth and development of the geological sciences. Baltimore: The Williams And Wilkins Company.

- [12] Bartholomew, M. (1973). “Lyell and evolution: an account of Lyell’s response to the prospect of an evolutionary ancestry for man”. The British Journal for the History of Science. 6 (3): 261–303.

- [13] Lyell, Sir Charles (1970). Wilson, Leonard G (ed.). Sir Charles Lyell’s Scientific Journals on the Species Question. Yale University Press.

- [14] Lyell Timeline via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #14 | Whewell's Ghost