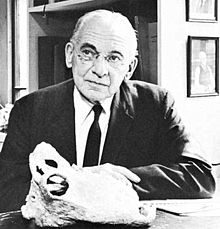

Alfred Romer (1894-1973)

On December 28, 1894, American paleontologist and biologist Alfred Sherwood Romer was born. Romer was a a specialist in vertebrate evolution. He studied the evolution of early vertebrates in biological terms of comparative anatomy and embryology. He researched muscle and limb evolution, the development and evolutionary history of cartilage and bone, and the structure and function of the nervous system.

Youth and Education

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of an editor, and sometimes owner, of several small-town newspapers in Connecticut and New York. During the year after high school Romer, who was not encouraged to go to university, worked as a railroad clerk. Finally, he decided otherwise entirely on his own and against family tradition and went to Amherst College, for which he had achieved a scholarship, with History and German Literature as a major. Early in his career, while in New York City, Romer visited the American Museum of Natural History, and its dinosaur exhibits sparked his interest in fossils. After taking a course in evolution under Frederic B. Loomis to fulfill a science requirement, Romer knew what he wanted to do.[2] At Amherst he achieved a Bachelor of Science Honours degree in Biology in 1917.

With the entrance of the U.S. into World War I, Romer joined the American Field Service in France and in the autumn of that year enlisted in the United States Army. On his return to the U.S. in 1919, he entered graduate school at Columbia University to work under William K. Gregory, an outstanding comparative anatomist (particularly of mammals) and evolutionist, pursuing with a M.Sc in Biology and graduating with a doctorate in zoology in 1921 with a thesis in comparative myology, the study of musculature. Romer joined the department of geology and paleontology at the University of Chicago as an associate professor in 1923. He was an active researcher and teacher. His collecting program added important Paleozoic specimens to the Walker Museum of Paleontology. In 1934 he was appointed professor of biology at Harvard University, where he became curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Museum of Comparative Zoology. After the death of Thomas Barbour, Romer succeeded him in 1946 as director of the museum, a position from which he retired in 1961.[3]

Research in Vertebrae Evolution

Romer was very keen in investigating vertebrate evolution. Comparing facts from paleontology, comparative anatomy, and embryology, he taught the basic structural and functional changes that happened during the evolution of fishes to primitive terrestrial vertebrates and from these to all other tetrapods. He always emphasized the evolutionary significance of the relationship between the form and function of animals and the environment.

Through his textbook Vertebrate Paleontology (1933) Romer laid the foundation for the traditional classification of vertebrates. In its three editions, this book shaped much of the thinking in the subject for several decades.[2] He drew together the by the time widely scattered taxonomy of the different vertebrate groups and combined them in a simplified scheme, emphasizing orderliness and overview. Based on his research of early amphibians, he reorganised the labyrinthodontians. Romer’s classification was followed by many subsequent authors, notably Robert L. Carroll, and is still in use. Romer published more than 200 papers. His studies of Permian and Triassic fossils had made Romer a champion of transatlantic continental connections long before the theory of plate tectonics.[3]

The Romer Gap

The “Romer gap” refers to a fossil-poor period of 360 million to 345 million years between the transition from Devonian to Carboniferous 360 million years ago that Romer described. Only from the middle of the sub-carboniferous period fossils could be found again. An explanation for the species gap is based on a reduction of the oxygen content to only 13 % (today: 21 %). A renewed decrease in oxygen partial pressure about 230 million years ago could explain the development of efficient respiratory systems, such as those found in dinosaurs or birds with their air sacs today. Accordingly, a high oxygen content would have favoured the formation of giant insects in the Upper Devonian about 420 million years ago. Due to the diffusion-controlled respiratory system (trachea), insects with a body length of more than about 15 centimeters are not possible today.

Later Years

Romer retired from Harvard in 1965 and, with characteristic energy, used his leisure for world travel, fossil collecting, lecturing, attending conferences, and visiting museums. He continued to write scientific papers, and his studies extended the understanding of the course of evolution of the lower vertebrates. His basically conservative approach focussed attention upon the significance of form and function in relation to environment as the key to evolutionary progress. Documentation of the slowly changing flow through time, as envisaged by Darwin, emerges clearly from Romer’s studies of the evolution of extinct fishes, amphibians, and reptiles.[2]

Alfred Romer died on November 5, 1973, at age 78.

Works by Alfred Romer:

- Romer, A.S. 1933. Vertebrate Paleontology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. (2nd ed. 1945; 3rd ed. 1966)

- Romer, A.S. 1933. Man and the Vertebrates. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. (2nd ed. 1937; 3rd ed. 1941; 4th ed., retitled The Vertebrate Story, 1949)

- Romer, A.S. 1949. The Vertebrate Body. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. (2nd ed. 1955; 3rd ed. 1962; 4th ed. 1970)

- Romer, A.S. 1949. The Vertebrate Story. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. (4th ed. of Man and the Vertebrates)

- Romer, A.S. 1956. Osteology of the Reptiles. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Romer, A.S. 1968. Notes and Comments on Vertebrate Paleontology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Romer, A.S. & T.S. Parsons. 1977. The Vertebrate Body. 5th ed. Saunders, Philadelphia. (6th ed. 1985)

Conrad Wilson, Mass Extinctions, Ray-Finned Fishes, and the Closing of Romer’s Gap, [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Edwin H. Colbert: Alfred Romer — Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences

- [2] Alfred Sherwood Romer, American biologist, at Britannica Online

- [3] “Romer, Alfred Sherwood.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

- [4] Alfred Sherwood Romer at Wikidata

- [5] Conrad Wilson, Mass Extinctions, Ray-Finned Fishes, and the Closing of Romer’s Gap, Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology @ youtube

- [6] Timeline for Alfred Sherwood Romer, via Wikidata