Carl von Ossietzky (1889-1938), Stamps of Germany, 1989

On October 3, 1889, German pacifist and Nobel Laureate Carl von Ossietzky was born. He received the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German re-armament. In the course of his publications of Germany‘s alleged violation of the Treaty of Versailles by rebuilding an air force he was convicted of high treason and espionage in 1931.

“Germany is the only country where lack of political empowerment secures the way to the highest honorary offices.”

– Carl von Ossietzky (Die Weltbühne)

Carl von Ossietzky – Early Years

Carl von Ossietzky was born in 1889 in Hamburg to the married couple Carl Ignatius von Ossietzky and Rosalie, née Pratzka. His father Carl Ignatius (1848-1891) was the son of a district official from Upper Silesia. After moving to Hamburg he worked as a stenographer in the law firm of the senator and later mayor of Hamburg, Max Predöhl. He also ran a restaurant. When his father died in Carl’s third year, his sister took over Carl’s upbringing, the only child remaining, while his mother continued to take care of the restaurant. Ten years after her husband’s death, Rosalie von Ossietzky married sculptor and social democrat Gustav Walther, and both took the boy with them. Walther aroused Ossietzky’s interest in politics. They attended party events where SPD leader August Bebel spoke, which left a lasting impression on Ossietzky. Often, Ossietzky left school early to read Schiller or Goethe and even when he started working in his first job for the administration of justice, he enjoyed theater visits and long reading nights. Next to literary aspects, Ossietzky believed in science, technology and their ability to improve overall living conditions and followed the works of Ernst Haeckel [5]. As he was denied an academic career, he applied at the age of 17 for a position with the Hamburg administration of justice. It was only thanks to the intervention of his advocate Predöhl that he was admitted to the recruitment test at all. Finally, Ossietzky had moved up to first place in the waiting list for “Auxiliary writer to be hired” and entered the judicial service on 1 October 1907. In 1910 he was transferred to the land registry office on the basis of acceptable performance.

The War and Political Journalism

In 1911 Ossietzky sent his first contribution to the weekly newspaper Das freie Volk, the publication organ of the Democratic Association. In the following years, this initiative led to the development of a regular staff. For the first time Ossietzky became the editorial journalist of a magazine. In 1914 he became acquainted with the judiciary in a way he was unaccustomed to: on the basis of the article “The Erfurt Judgement” he was accused of “public insult” because he had criticised the military justice of the time too strongly. At the beginning of the First World War, Carl von Ossietzky was initially found to be unfit. However, the war-induced changes in the media made it impossible for him to continue earning his living as a journalist critical of the military and later even pacifist. He therefore returned to judicial service in January 1915. In the summer of 1916 he was finally drafted and sent to the German Western Front as a reinforcing soldier. By this time he had freed himself from his initial enthusiasm for war and gave pacifist lectures in Hamburg, where he had been elected to the board of the local group of the German Peace Society (DFG). At the end of the war Ossietzky returned to Hamburg, where he once again resigned from the judiciary.

Moving to Berlin

However, it proved difficult to establish a journalistic existence. Ossietzky accepted a low-paid position as an editor at Pfadweiser-Verlag. He also published the zero number of the monistic magazine Die Laterne. When he finally had the opportunity to become secretary of the DFG in Berlin in mid-1919, Ossietzky moved to the Reich’s capital. There, in October 1919, he was one of the founding members of the Friedensbund der Kriegsteilnehmer (FdK), which he founded together with Kurt Tucholsky and other pacifists. From January 1920 to March 1922 he wrote under the pseudonym Thomas Murner in the Monistic Monthly Bulletins the column Von der deutschen Republik. From 1920 to 1924 he worked for the Berliner Volks-Zeitung, first as a foreign policy officer and later as an editor. In addition, he was heavily involved in the “Never Again War” movement, which had been founded under the leadership of the FdK.

Pacifism and Journalism are Not Enough

“Political journalism is not life insurance: risk is the best incentive.”

– Carl von Ossietzky, In: Die Weltbühne, Volume 28, Number 19, May 10, 1932, Volume 1, Verlag der Weltbühne, Charlottenburg, p. 689,

Ossietzky’s pacifist and journalistic work, which included publications in numerous media, was obviously not enough to anchor the ideas of democracy and republic more firmly in the German population. In March 1924 he founded the Republican Party (RPD) together with journalist Karl Vetter. Ossietzky formulated the party program, which was based on the ideals of the March Revolution of 1848 and the November Revolution of 1918. It provided for the strengthening of the state vis-à-vis the private sector for the common good and contained cautious demands for the socialization of industry. With the vague concept of a democratic state socialism, the party differed from both the SPD and the KPD. Ossietzky was not to give up this position until the end of the Weimar Republic, which kept him at a distance from the two major parties of the labor movement. Since the party received only 0.17 percent of the vote in the May 1924 Reichstag election and no mandate, it was soon dissolved.

After his unsuccessful excursion into party politics, Ossietzky did not return to the Volkszeitung, but became an employee and soon after editor of Stefan Großmanns and Leopold Schwarzschild’s magazine Das Tage-Buch. The cooperation with the renowned journalists did not last long, as Ossietzky felt that both of them did not attack the military sharply enough and preferred to write about important topics themselves.

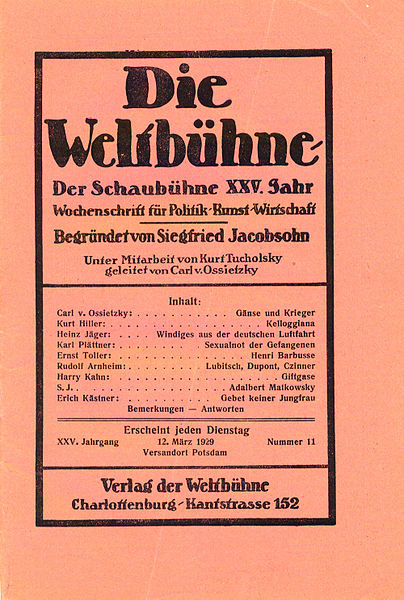

Weltbühne cover, 12 March 1929

Die Weltbühne

At Tucholsky’s suggestion, Siegfried Jacobsohn, editor of the Berlin weekly Die Weltbühne, had sought Ossietzky’s collaboration from summer 1924 onwards. It was not until April 1926 that Ossietzky’s first political editorial appeared in the paper. After Jacobsohn’s death in 1927, he became editor and chief editor of the Weltbühne with the collaboration of Kurt Tucholsky. Under Ossietzky’s leadership, the Weltbühne retained its significance as an undogmatic forum for the radical democratic, bourgeois left. The fact that Ossietzky gained a great reputation in this function is also shown by the fact that he took over the chairmanship of the committee after the Berlin Blutmai in May 1929, which was to clarify the background to the violent police operation.

The Weltbühne Trial

Ossietzky finally came to the attention of the international public through his indictment in the so-called Weltbühne trial. The article that led to the indictment had already appeared in March 1929 and had uncovered the prohibited armament of the Reichswehr. In this context, the extent to which Ossietzky was a whistleblower is often discussed. At the end of 1931, Ossietzky and aircraft expert Walter Kreiser were finally sentenced to 18 months in prison for betraying military secrets. Unlike Kreiser, however, Ossietzky strictly refused to escape prison by fleeing abroad. An episode of Walter Mehring, a member of the Weltbühne staff, tells us that the later Reich Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher personally came to the editorial office of the magazine to persuade Ossietzky to leave for Switzerland. Ossietzky commented on this attempt with the words: “Now the gentlemen who brought me the prison soup should also spoon it out themselves.“

Imprisonment un Berlin-Tegel

“To have been in prison is a great experience that no political man can erase from his life.”

– Carl von Ossietzky, Return. In: Die Weltbühne, Volume 28, Number 52, December 27, 1932, Volume 2, Verlag der Weltbühne, Charlottenburg, p. 925

Ossietzky provoked an outcry of indignation in the democratic and social democratic press when he recommended before the Reich presidential election in March/April 1932 to vote for the communist candidate Ernst Thälmann. His recommendation seems all the more astonishing when one considers that Ossietzky had accused the KPD in January 1932 of having “reacted in the most impossible way possible” with Thälmann’s nomination and of having prevented a common left-wing candidate. In his rejection of the “political zero” Hindenburg, Ossietzky took no account of the fact that at the same time he had to decide on his petition for clemency in the world stage process. Since the request was rejected at the end of March 1932, Ossietzky was sentenced to prison in Berlin-Tegel on May 10, 1932. Numerous friends and political companions did not miss the opportunity to accompany Ossietzky to the gate of the prison. Due to a Christmas amnesty for political prisoners, Ossietzky was released prematurely on December 22, 1932, after 227 days in prison.

National Socialism and again Imprisonment

A committed pacifist and democrat, he was arrested again on February 28, 1933 at the instigation of National Socialists and interned in Berlin-Spandau prison. Until the end, Ossietzky had hoped that a united front of Social Democrats and Communists could oppose the threatening Nazi dictatorship. He believed that the NSDAP would break with its internal contradictions after taking over the government. Private reasons also prevented him from escaping the expected arrest by fleeing abroad. On 6 April 1933, Ossietzky was deported from Spandau to the newly erected concentration camp Sonnenburg near Küstrin. There he was severely maltreated, as were the other prisoners. The conditions in the camp, which was initially run by the SA, finally led to the SS under Heinrich Himmler professionalizing the camp system in the spring of 1934. Ossietzky and other known prisoners were transferred from Sonnenburg to the Esterwegen concentration camp in northern Emsland. There, the prisoners were deployed under unbearable conditions to drain the Emsland raised bogs. At the end of 1934, the completely emaciated Ossietzky was transferred to the sick bay.

Carl von Ossietzky. Publicist, as a prisoner in a concentration camp Esterwegen

The Nobel Peace Price Campaign

Already in 1934, Ossietzky’s friends Berthold Jacob in Strasbourg and Kurt Grossmann in Prague, on behalf of the German League for Human Rights (of which he had belonged to the board from 1926 to 1927), submitted the first official application for Ossietzky’s Nobel Peace Prize. But this attempt was doomed to failure because the application deadline for 1934 had already expired and the Human Rights League was not entitled to propose. But since Jacob had informed the press about the proposal, the attention was directed to the concentration camp prisoner Ossietzky. The campaign continued unabated in 1936, which finally led to Ossietzky being released from the concentration camp shortly before the 1936 Olympic Games and transferred to the State Hospital in Berlin. On November 7, 1936, he was officially released from prison and first moved into a room in the Westend Hospital, under constant Gestapo surveillance. Despite these concessions, the international campaign organized in Norway by the German emigrant Willy Brandt had meanwhile achieved its goal. On 23 November 1936, Carl von Ossietzky was retroactively awarded the Nobel Peace Prize of 1935.

Nobel Peace Price and Death

“Where men fail, you call for the man. Fascism, which appears everywhere else, everywhere in new national masquerade, shows in all countries a common characteristic: the longing for the dictator. The slackened peoples are looking for a brain that thinks for them, for a back that carries them”.

– Carl von Ossietzky, World reaction – your nonsense and your sense. In: Berliner Volks-Zeitung, 13 May 1923

The then Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring personally urged Ossietzky not to accept the prize. But in vain. The Gestapo refused to let Ossietzky travel to Oslo to receive the prize. Adolf Hitler then ordered that no Reich German should accept a Nobel Prize in the future. A few days after the Nobel Prize was awarded, Ossietzky was transferred to the Nordend Hospital (Berlin-Niederschönhausen), where a special TBC department existed. Maud von Ossietzky played a tragic role in the attempt to invest the prize money associated with the Nobel Peace Prize. She was taken in by the lawyer Kurt Wannow, who assured her that he would administer the prize money of almost 100,000 Reichsmark. But Wannow embezzled the money so that the trial finally took place. On 4 May 1938 Ossietzky died of tuberculosis in the hospital Nordend. He left behind his wife Maud and daughter Rosalinda, who were able to emigrate to Sweden via England.

The Dangerous Prize – about whistleblower Carl von Ossietzky, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Grandiose Anpassung: Der Spiegel 39/1991

- [2] Ossietzky at the Nobel Prize website

- [3] Carl von Ossietzky – Friedensnobelpreisträger, Journalist, politischer Pazifist

- [4] George Orwells Opposition to Totalitarianism

- [5] Ernst Haeckel and the Phyletic Museum, SciHi Blog

- [6] Newspaper clippings about Carl von Ossietzky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [7] Works by or about Carl von Ossietzky at Internet Archive

- [8] Works by and about Carl von Ossiezky at Wikisource (in German)

- [9] Carl von Ossietzky at Wikidata

- [10] The Dangerous Prize – about whistleblower Carl von Ossietzky, Exhibition at the Nobel Peace Center, June 2016 – February 2017, Nobel Peace Center @ youtube

- [11] Von Ossietzky, Carl. The Stolen Republic: Selected Writings of Carl Von Ossietzky (Lawrence and Wishart, 1971)

- [12] Carl. The Stolen Republic: Selected Writings of Carl Von Ossietzky (Lawrence and Wishart, 1971).

- [13] Tres, Richard: “The Man without a Party: The Trials of Carl von Ossietzky.” Beacon Publishing Group, 2019

- [14] Ossietzky Timeline via Wikidata