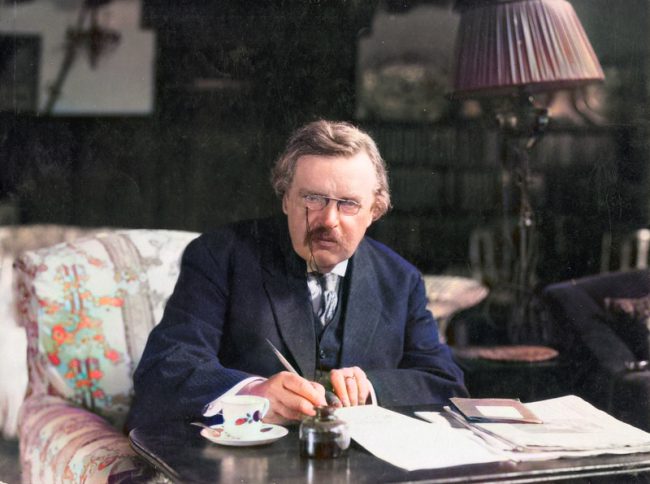

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936)

On May 29, 1874, English writer, philosopher, lay theologian, and literary and art critic Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born. Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown, and wrote on apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. I remember that I really enjoyed reading Chesterton’s short novel The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), somehow a political satire or almost a fantasy novel: A conspiracy of anarchist terrorists at the beginning of the 20th century develops in it, under increasing alienation of reality, into a crazy divine spectacle.

“The cause which is blocking all progress today is the subtle scepticism which whispers in a million ears that things are not good enough to be worth improving. If the world is good we are revolutionaries, if the world is evil we must be conservatives. “

– G. K. Chesterton, The Defendant (1901)

C. K. Chesterton – First Journalistic Work

C. K. Chesterton was born in 1874 in Campden Hill in the London district of Kensington as the son of Edward Chesterton, a London estate agent, and Marie Louise, née Grosjean. The family was of Protestant faith and belonged to the Unitarian community. He was educated at St Paul’s School. Afterwards he attended the Slade School of Art to become an illustrator. He also attended lectures in literature at University College London, but did not earn a degree. 1896-1902 Chesterton worked for the London publishing house Redway, and T. Fisher Unwin. During this time he did his first journalistic work as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1901 he married Frances Blogg. In 1902, Chesterton received a weekly column in the Daily News, and in 1905, another weekly column in The Illustrated London News, for which he wrote for the next 30 years.

A Strange Contemporary

According to his own account, the occult fascinated him, and he experimented with Ouija with his brother Cecil. Later he turned back to Christianity, which led to his entry into the Roman Catholic Church in 1922. Chesterton was about 1.93 m tall and weighed about 134 kg. His belly circumference was the subject of well-known anecdotes: He said to his friend George Bernard Shaw,[1] “Looking at you, you’d think there was a famine in England.” Shaw returned, “Looking at you, anyone would think you caused it.” He usually wore a cape and a crushed hat and a sword cane and had a cigar hanging from his mouth. He often forgot where he was going and missed the train that was going to take him there. It is reported that he sent his wife several telegrams from distant places like “Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?” to which she replied: “Home“.

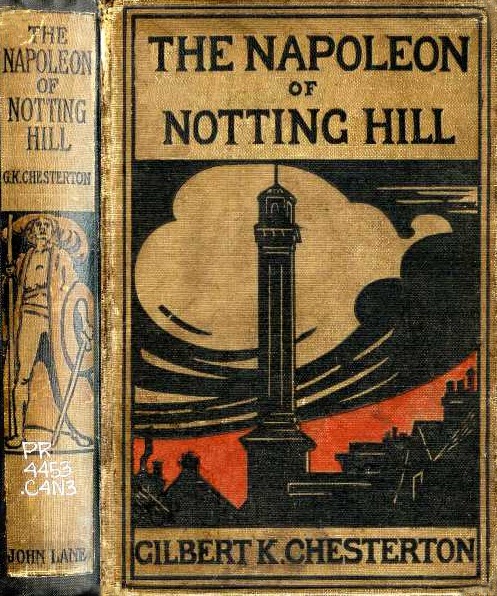

The Napoleon of Notting Hill 1904

Daring Leaps of Thought

In his novels, essays and short stories, Chesterton dealt intensively with modern philosophies and schools of thought. His often daring leaps of thought and his bringing together of seemingly irreconcilable ideas are well known, often with surprising results. His way of argumentation has been strikingly described as a “spiritual hussar ride”. Chesterton held public debates with G. B. Shaw, H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell and Clarence Darrow, among others. Perhaps his most important discussion partner was Shaw, with whom he had a cordial friendship while rejecting his views. After his autobiography he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent movie, which was never released. He fought against various ideas and theories that were often and gladly advocated at the beginning of the 20th century; above all, he spoke out against euthanasia and race studies, as well as against any idea of eugenics. He took a critical look at Nietzsche‘s thoughts on the superhuman. He rejected British colonialism and supported Irish independence.

Chesterton and Anticapitalism

Chesterton admired the Middle Ages, which in his opinion were often depicted unfairly negative in modern times. He argued that democracy, by its own nature, should listen to the voice of the poor and slum dwellers, rather than decide on them from above “for their own good” (“Instead of asking ourselves what to do with the poor, we should rather ask ourselves what the poor will do with us“). In terms of economic policy, he called for a limitation of the power of big capital while at the same time promoting small-scale property (“Everyone should be able to own a cow and three acres of land“, “The problem of capitalism is not that there are too many capitalists, but that there are too few“). He called this distributism. His opposition to capitalism resulted in anti-Semitic patterns of thought: he saw capitalism and Marxism as instruments of the Jews to achieve world domination, believed that the Boer War was being waged because of the financial interests of the Jews in South Africa, and in The New Witness magazine spoke out against a policy that allowed Jews to rise up in politics and society. In his paper The New Jerusalem (1920) he advocated the creation of a home for the Jews. However, Chesterton also opposed the ideology of National Socialism.

Father Brown

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4,000 essays (mostly newspaper columns), and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, Catholic theologian and apologist, debater, and mystery writer. However, Chesterton’s most famous literary creation is Father Brown, which is the focus of a total of 49 short stories, the first of which appeared in 1910 and which were published in five volumes. Brown is a clergyman who solves even the most seemingly mysterious criminal cases with psychological sensitivity and by drawing logical conclusions. In contrast to other well-known novel heroes such as Sherlock Holmes [2] and Agatha Christie‘s Hercule Poirot,[3] Brown’s focus is not so much on the external logic of the crime, but on the inner logic and motivation of the perpetrator. In 1953 Alec Guinness played the detective pastor in Father Brown. Not least from this encounter with Chesterton later resulted Guinness’ own conversion to the Catholic Church. Of Chesterton’s nonfiction, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. Chesterton’s writing has been seen by some analysts as combining two earlier strands in English literature. Dickens’ approach is one of these. Another is represented by Oscar Wilde [4] and George Bernard Shaw, whom Chesterton knew well: satirists and social commentators following in the tradition of Samuel Butler, vigorously wielding paradox as a weapon against complacent acceptance of the conventional view of things.

The End

Chesterton was president of the Detection Club from 1930 to 1936, an association of mystery writers who established rules for a “fair mystery novel“. Chesterton died at the age of 62 on 14 June 1936 at his home in Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire. The homily at Chesterton’s Mass for the Dead in Westminster Cathedral was delivered by Ronald Knox. He was buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic cemetery. Chesterton’s estate was estimated at 28,389 pounds sterling, which today would be about 2.6 million US dollars.

“G.K. Chesterton on Humor” A Lecture by Ian Ker April 4th, 2012, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] George Bernard Shaw – Playwright, Critic, Polemicist and Political Activist, SciHi Blog

- [2] Elementary, my Dear Watson! – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and his famous Sherlock Holmes, SciHi Blog

- [3] Agatha Christie – Explorer, Archaeologist, and World Famous Author of Detective Stories, SciHi Blog

- [4] Oscar Wilde – One of the Most Iconic Figures of Victorian Society, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by or about G. K. Chesterton at Internet Archive

- [6] The American Chesterton Society

- [7] G.K. Chesterton research collection at The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College

- [8] Newspaper clippings about G. K. Chesterton in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- [9] Texts of G. K. Chesterton at Wikisource

- [10] G. K. Chesterton at Wikidata

- [11] “G.K. Chesterton on Humor” A Lecture by Ian Ker April 4th, 2012,Lumen Christi Institute @ youtube

- [12] Braybrooke, Patrick (1922). Gilbert Keith Chesterton. London: Chelsea Publishing Company.

- [13] Chesterton, Cecil (1908). G.K. Chesterton: A Criticism. London: Alston Rivers (Rep. by John Lane Company, 1909).

- [14] Timeline for G. K. Chesterton, via Wikidata