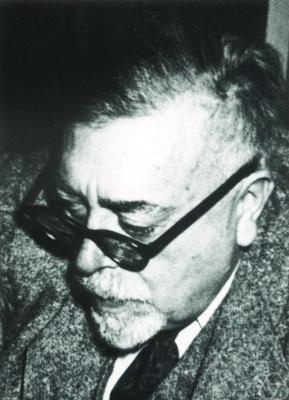

Norbert Wiener (1894-1964)

On November 26, 1894, American mathematician Norbert Wiener was born. Wiener established the science of cybernetics, a term he coined, which is concerned with the common factors of control and communication in living organisms, automatic machines, and organizations. He attained international renown by formulating some of the most important contributions to mathematics in the 20th century.

“Scientific discovery consists in the interpretation for our own convenience of a system of existence which has been made with no eye to our convenience at all.

One of the chief duties of a mathematician in acting as an advisor to scientists is to discourage them from expecting too much of mathematicians.”

– Norbert Wiener, as quoted in Comic Sections (1993) by D MacHale

A Child Prodigy

Wiener was born in Columbia, Missouri, USA, the first child of Leo Wiener, a professor for slavic languages at Harvard, and Bertha Kahn, both Jews of Polish and German origin, respectively. Norbert Wiener became a famous child prodigy, who was educated by his father Leo at home. After graduating from Ayer High School in 1906 at 11 years of age, Wiener entered Tufts College. He was awarded a BA in mathematics in 1909 at the age of 14, whereupon he began graduate studies of zoology at Harvard. In 1910 he transferred to Cornell to study philosophy and back to Harvard, where he was strongly influenced by the fine teaching of Edward Huntington on mathematical philosophy. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard at the age of 18 with a dissertation on mathematical logic supervised by Karl Schmidt.

Russell and Hilbert

In 1914, Wiener traveled to Europe, to study under Bertrand Russell [7] and G. H. Hardy [10] at Cambridge University, and by David Hilbert [6] and Edmund Landau at the University of Göttingen. During 1915–16, he taught philosophy at Harvard, then was an engineer for General Electric and wrote for the Encyclopedia Americana. After the First World War, Wiener became an instructor of mathematics at MIT, where he spent the remainder of his career, becoming promoted eventually to Professor. While working at MIT, he maintained numerous contacts that led to many trips to the USA, Mexico, Europe and Asia, benefiting from his gift for languages (ten languages).

During the 1920s Wiener did highly innovative and fundamental work on what are now called stochastic processes and, in particular, on the theory of Brownian motion and on generalized harmonic analysis, as well as significant work on other problems of mathematical analysis. In 1933 Wiener was elected to the National Academy of Sciences but soon resigned, repelled by some of the aspects of institutionalized science that he encountered there.[2] During World War II Wiener worked on the problem of aiming gunfire at a moving target. The ideas that evolved led to Extrapolation, Interpolation, and Smoothing of Stationary Time Series (1949), which first appeared as a classified report and established Wiener as a co-discoverer, with the Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov,[11] of the theory on the prediction of stationary time series. This work should finally led him to formulate the concept of cybernetics.The term he coined is the root of neologisms such as cyberspace.

Cybernetics

During the Second World War, the further development of communications engineering and communication theory led him to cybernetics. Cybernetics was born in 1943, when he and John von Neumann,[12] engineers and neuroscientists, met in an interdisciplinary meeting to explore the similarities between the brain and computers. In 1948 his book Cybernetics: or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine appeared. He explained the parallels between organic and inorganic information processing. One example is the control circuit that can be discovered in steam engines and thermostats as well as in the human body. “Cybernetics” also compared the brain with the analog and digital computers existing in 1948. Towards the end it brought a biting criticism of the emerging information society and closed with a note about chess programs. For a scientific book it was extremely popular, and Wiener became known in a much broader scientific community. Cybernetics is interdisciplinary in nature; based on common relationships between humans and machines, it is used today in control theory, automation theory, and computer programs to reduce many time-consuming computations and decision-making processes formerly done by human beings. Wiener worked at cybernetics, philosophized about it, and propagandized for it the rest of his life, all the while keeping up his research in other areas of mathematics.[3]

Artificial Intelligence

“The mechanical brain does not secrete thought “as the liver does bile,” as the earlier materialists claimed, nor does it put it out in the form of energy, as the muscle puts out its activity. Information is information, not matter or energy. No materialism which does not admit this can survive at the present day.”

– Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics (1948)

Wiener’s fame after the war helped MIT to recruit a research team in cognitive science, composed of researchers in neuropsychology and the mathematics and biophysics of the nervous system, including Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts. These men later made pioneering contributions to computer science and artificial intelligence. In 1949 Wiener designed a robot on three wheels. The moth reacted to light and was one of the earliest mobile automatons that imitated the behavior of living beings. It emerged more or less parallel to the electric turtles created by neurologist William Grey Walter in England. Along with stationary learning machines, the cute cybernetic animals were science’s most important contribution to artificial intelligence. Wiener later helped develop the theories of cybernetics, robotics, computer control, and automation. Wiener always shared his theories and findings with other researchers, and credited the contributions of others. These included Soviet researchers and their findings. Wiener’s acquaintance with them caused him to be regarded with suspicion during the Cold War. He was a strong advocate of automation to improve the standard of living, and to end economic underdevelopment. Wiener always pursued a realistic approach, as in his last writing: God & Golem, Inc; A Comment on Certain Points Where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion. He was optimistic about new technical possibilities, such as the control of prostheses to replace limbs and sensory organs; he considered it difficult to intervene in social and especially economic processes.

Wiener’s article “A Scientist Rebels” for the January 1947 issue of The Atlantic Monthly urged scientists to consider the ethical implications of their work. After the war, he refused to accept any government funding or to work on military projects. Wiener’s vision of cybernetics had a powerful influence on later generations of scientists, and inspired research into the potential to extend human capabilities with interfaces to sophisticated electronics. He changed the way everyone thought about computer technology, influencing several later developers of the Internet, most notably J.C.R. Licklider.[5] He died in 1964, aged 69, in Stockholm, Sweden.

Norbert Wiener – Men, Machines, and the World About Them (1950), [15]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] O’Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., “Norbert Wiener”, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- [2] Norbert Wiener at Encyclopedia Britannica/

- [3] Norbert Wiener, A1909, H1946 at Tufts University

- [4] David Jerison and Daniel Stroock: Norbert Wiener, Notes of the AMS, Vol 42, no.4

- [5] Norbert Wiener and Cybernetics – Living Internet

- [6] David Hilbert’s 23 Problems, SciHi Blog

- [7] The time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time – Bertrand Russell, Logician and Pacifist, SciHi Blog

- [8] J.C.R. Licklider and Interactive Computing, SciHi Blog

- [9] Norbert Wiener at Wikidata

- [10] G. H. Hardy and the aesthetics of Mathematics, SciHi Blog

- [11] Kolmogorov and the Foundations of Probability Theory, SciHi Blog

- [12] John von Neumann – Game Theory and the Digital Computer, SciHi Blog

- [13] Norbert Wiener at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- [14] McCavitt, Mary Jane (September 2, 2009), Guide to the Papers of Norbert Wiener

- [15] Norbert Wiener – Men, Machines, and the World About Them (1950), Biophily2 @ youtube

- [16] Norbert Wiener Timeline via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #24 | Whewell's Ghost