Andreas Osiander (1496/94 – 1552) by Georg Pencz, paper drawing 1544 in Rome

On October 17, 1552, German Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander passed away. Osiander published a corrected edition of the Vulgate Bible in 1522 and oversaw the publication of the book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolution of the celestial spheres) by Copernicus in 1543.[1] Osiander pursued mathematics as a hobby and edited Cardano‘s Artis Magnae, which introduced the theory of algebraic equations.

Andreas Osiander – Background

Andreas Osiander was born in Gunzenhausen, Principality of Ansbach, the son of Endres Osiander, a smith and his wife Anna Herzog. The father, however, is said to have made it to the position of a councilman in his hometown, the son was then sent to school in Leipzig and Altenburg. Osiander then studied at the University of Ingolstadt. However, Osianer did not follow the regular course of theological studies and did not acquire a theological degree. In 1520, he was ordained as a priest in Nuremberg and became a teacher of the Hebrew language with the Augustinians. One result of his studies was the publication of a Latin Bible, a Vulgate text improved from the basic text and the Greek translation. However, h earned his living by reading private masses in Nuremberg.

Osiander was considered an expert of the Hebrew language and Jewish mysticism. Unlike Luther, he sought a genuine dialogue with the Jews, vigorously advocated their rights, and rejected any form of anti-Judaism. In 1540, he published (anonymously) his work “Ob es wahr und glaublich sey, dass die Juden der christen kinder heymlich erwürgen und ir Blut gebrauchen” (Whether it is true and believable that the Jews are strangling the Christians’ children and using their blood), in which he refuted the accusation of ritual murder and other accusations against the Jews.[7]

Osiander and the Lutheran Reformation

In 1522, Osiander was accepted as a predicant at St. Lorenz in Nuremberg and quickly gained significant popularity. He declared himself to be a Lutheranian and also played a major role in converting Albert of Prussia, Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights to Lutheranism. He became, along with Dominicus Schleupner and Thomas Venatorius, the most influential preacher and, as spokesman for the Lutheran side at the religious discussion in March 1525, the reformer of the imperial city of Nuremberg. In the following years, he determined the implementation of Reformation preaching in new church and social orders through advice and expert opinions and defended the city’s Lutheran Reformation against Zwinglian and Anabaptist tendencies. The drafting of the Brandenburg-Nuremberg Church Order, which he had determined and which was exemplary for many Protestant churches, led to disputes with his colleagues and the council clerk Lazarus Spengler, so that Osiander’s influence in the church and city declined significantly after 1530, especially since he did not always follow the wishes of the council in the religious negotiations in the Schmalkaldic League and with the emperor. He then devoted himself more to his theological and other studies

De Revolutionibus

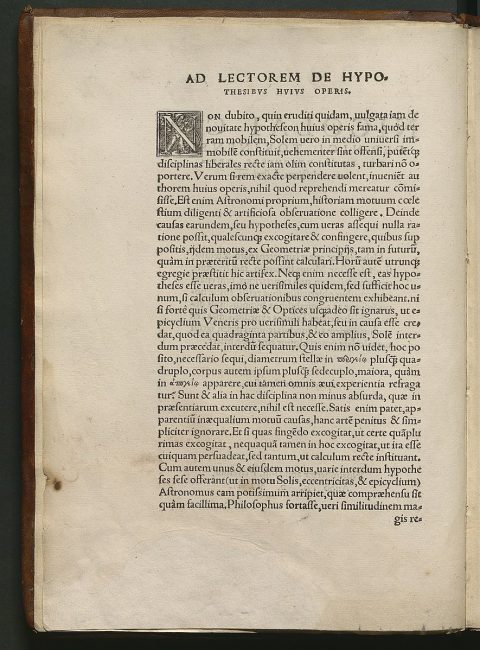

In 1543, Andreas Osiander oversaw the publication of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the revolution of the celestial spheres) by Copernicus. Osiander added a preface (ad lectorum) which suggested that the Copernicus’ described model is not necessarily true or probable, however he pointed out that they might be useful for mathematical purposes. Copernicus on the other hand might not have been aware of this addition to his work. This caused that many readers thought that Copernicus himself had not believed that his hypothesis was actually true and that Copernicus himself had written the preface since Osiander never signed it. However, “many historians are of the opinion that the ad lectorum saved the De revolutionibus from being condemned straight away, when it was published, and allowed the heliocentric hypothesis it contained to spread relatively unhindered and become established.”[3]

De Revolvtionibvs Orbium coelestium (1543), Ad Lectorem…

The Osiandrian Controversy

In 1549, Osiander was appointed by Duke Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach as a professor of theology at the still young Albertus University in Königsberg, founded in 1544. There he got into a heated argument with the followers of Philipp Melanchthon,[5] Luther’s close companion. The dispute was about the doctrine of justification, one of the core statements of Reformation theology. For Melanchthon, a sinner remained profoundly a sinner even after justification before Christ; Osiander, on the other hand, was of the opinion – similar to the position of the Eastern churches – that Christ’s righteousness is implanted in man through faith and thus becomes an essential part of the believer. This so-called Osiandrian controversy agitated and divided Protestantism for many years. In the end, Osiander and his followers went their own ways throughout their lives on this theological question, which was important for the Reformation.

Andreas Osiander died on October 17, 1552, in Königsberg.

General Astronomy: Lecture 3 – The Copernican Revolution, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Nicolaus Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model, SciHi Blog

- [2] Gerolamo Cardano and Physician, Mathematician, and Gambler, SciHi Blog

- [3] The greatest villain in the history of science?, The Renaissance Mathematicus, Dec 19, 2015.

- [4] Wilhelm Möller: Osiander, Andreas. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Band 24, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, S. 473–483.

- [5] Philipp Melanchton – the First Systematic Theologician of the Protestant Reformation, SciHi Blog

- [6] Emanuel Hirsch: Die Theologie des Andreas Osiander und ihre geschichtlichen Voraussetzungen; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1919.

- [7] Andreas Osiander: Ob es wahr und glaublich sei … Eine Widerlegung der judenfeindlichen Ritualmordbeschuldigung Hrsg. von Matthias Morgenstern und Annie Noblesse-Rocher; Studien zu Kirche und Israel. Kleine Reihe 2; Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2018

- [8] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Osiander, Andreas“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 350.

- [9] Edward C. Friedrich, Osiander – A Man for All Churches in an Ecumenical Age, Metropolitan North-South Pastoral Conference November 17, 1980 St. James, Milwaukee

- [10] Osiander at Wikidata

- [11] General Astronomy: Lecture 3 – The Copernican Revolution, Spahn’s Science Lectures @ youtube

- [12] Timeline of 16th century German theologicians, via Wikidata and DBpedia