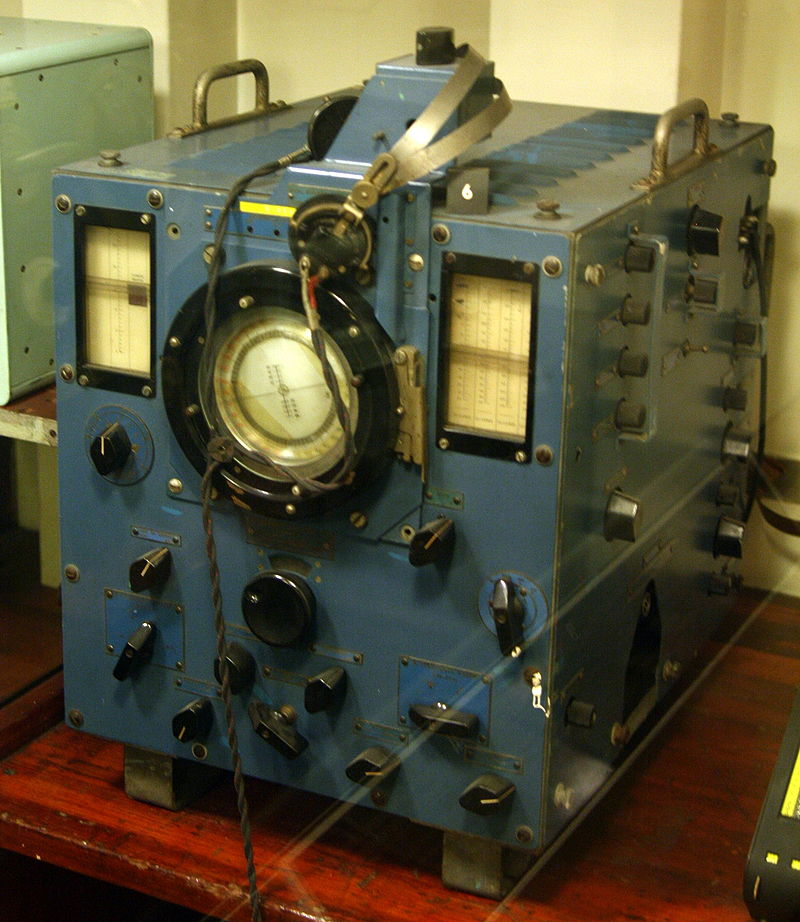

FH4 “Huff-duff” equipment on the museum ship HMS Belfast

On December 29, 1905, French engineer Henri Gaston Busignies was born. Busignies is best known for his contributions to radar, radio communication, and radio navigation. His invention (1936) of high-frequency direction finders (HF/DF, or “Huff-Duff“) permitted the U.S. Navy during World War II to detect enemy transmissions and quickly pinpoint the direction from which a radio transmission was coming.

Early Years

Henri Gaston Busignies was born in Sceaux, in suburban Paris, France, the son of a mechanical engineer. He became a ham radio operator as a boy, but found the equipment itself more interesting than receiving faraway signals. He attended Jules Ferry College in Versailles, and completed his degree in electrical engineering at the Institute Normal Electro Technique in Paris in 1926, having obtained his first patent, for a radio compass. In 1928 Busignies joined ITT Corporation‘s Paris Laboratories, where he developed radio direction finders, airplane radio navigation devices, and early radar systems. In 1936 his equipment automatically guided an airplane from Paris to Réunion island off the coast of Madagascar, in the first practical demonstration of an aircraft guidance system.

The Huff-Duff System

During World War II his inventions were instrumental in radio direction finding, including four secret patents relating to the automatic high-frequency direction finding (HF/DF, better known as Huff-Duff) system used to locate German U-boats. HF/DF was primarily used to catch enemy radios while they transmitted, although it was also used to locate friendly aircraft as a navigation aid. HF/DF used a set of antennas to receive the same signal in slightly different locations or angles, and then used the slight differences in the signal to display the bearing to the transmitter on an oscilloscope display. The basic technique remains in use to this day as one of the fundamental disciplines of signals intelligence, although typically incorporated into a larger suite of radio systems and radars instead of being a stand-alone system. he system was initially developed by Robert Watson-Watt starting in 1926, as a system for locating lightning. Its role in intelligence was not developed until the late 1930s.[4]

Actually, radio direction finding was a widely used technique even before World War I, used for both naval and aerial navigation. The basic concept used a loop antenna, in its most basic form simply a circular loop of wire with a circumference decided by the frequency range of the signals to be detected. When the loop is aligned at right angles to the signal, the signal in the two halves of the loop cancels out, producing a sudden drop in output known as a “null”.

French engineers Maurice Deloraine and Henri Busignies took their share in automating the system just prior to the opening of World War II. Their system motorized the search coil as well as a circular display card, which rotated in sync. A lamp on the display card was tied to the output of the goniometer, and flashed whenever it was in the right direction. When spinning quickly, about 120 RPM, the flashes merged into a single (wandering) dot that indicated the direction.

Moving to the U.S.

With the fall of Paris in 1940, there was a scramble to keep the electronic work that was being done by the ITT Paris Laboratory for the French military away from the Germans. ITT executives in New York arranged to smuggle their top researchers out of occupied France to the U.S. Busignies was one of the first three top men tapped for the escape via a secret rendezvous in Lyon in unoccupied France; then to Algiers, Rabat, Tangier – all in North Africa, and Lisbon, Portugal. Finally, by ship the three men and their families would arrive in the U.S.[2] Busignies had escaped from German-occupied Paris with his wife and working models, ultimately making his way to the United States, where the inventions were implemented first along the East Coast, then the West Coast, with another 30 to 40 fixed stations located around the world. About 1,000 smaller systems were installed on aircraft carriers and destroyers, as well as a further 1,500 mobile systems for the Army Signal Corps. Henri Busignies was also closely involved in early development of Moving Target Indication (MTI) radar during the war.

After the War

After the war, Henri Busignies remained in the United States, where he rose steadily through ranks of ITT’s senior management, ultimately becoming the corporation’s Chief Scientist. His inventions included contributions to Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) technology, conical scanning and 3-dimensional radar, gunfire and shell trajectory control, and deception systems. He also played a large role in development of ILS, TACAN, VORTAC, phased arrays for communications, and the use of dipole needles in orbit for reflection of radio waves (Project West Ford). In the course of his career, Busignies was promoted to Vice President of ITT in 1960 and retired as Chief Scientist of his company in 1975. Busignies was an IEEE Fellow, and given an honorary Doctor of Science by Newark College of Engineering (1958), and the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute (1971). He received numerous other awards and honors during his career, including notably the IRI Medal from the Industrial Research Institute (1971), the IEEE Edison Medal (1977), and the Armstrong Medal from the Radio Club of America. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering (1966).

Henri Gaston Busignies died on June 20, 1981 in Antibes on the French Riviera, at age 76.

Hugh Griffiths, RSGB Convention lecture 2017 – Reflections on the History of Radar, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] HENRI G. BUSIGNIES, INVENTOR-EXECUTIVE, NY Times, Obituary, June 21, 1981

- [2] Henri Busignies, at Engineering and Technology History Wiki

- [3] Henri-Gaston Busignies, French engineer, at Britannica Online

- [4] Robert Alexander Watson-Watt and the Radar Technology, SciHi blog, February 26, 2016.

- [5] Memorial Tributes: National Academy of Engineering, Volume 2 (1984), pp. 28-34

- [6] Henri Busignies at Wikidata

- [7] Hugh Griffiths, RSGB Convention lecture 2017 – Reflections on the History of Radar, Radio Society of Great Britain @ youtube

- [8] Timeline of Radar Pioneers via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #20 | Whewell's Ghost