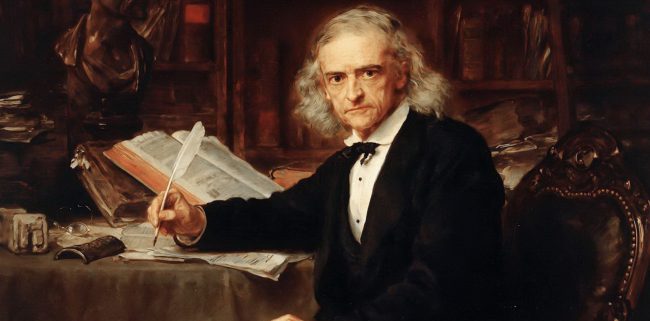

Theodor Mommsen (1817-1908), cropped painting by Ludwig Knaus – Nationalgalerie Berlin, A I 315

On November 30, 1817, German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician and archaeologist Theodor Mommsen was born. Mommsen was one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century. His work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. Mommsen received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902 for being “the greatest living master of the art of historical writing, with special reference to his monumental work, A History of Rome“.

“The great problem of man, how to live in conscioues harmony with himself, with his neighbor, and with the whole to which he belongs, admits of as many solutions as there are provinces in our Father’s kingdom; and it is in this, and not in the material sphere, that individuals and nations display their divergences of character.”

– Theodor Mommsen, The History of Rome – Volume 1

Theodor Mommsen – Early Life

Theodor Mommsen came from a pastor’s family; his father Jens Mommsen had been a pastor in Oldesloe in the Duchy of Holstein since 1821, where the eldest son Theodor grew up together with five siblings. The children gradually withdrew from their father’s strict Christian beliefs, but Mommsen remained a convinced liberal Protestant until the end of his life, with a clear aversion to Catholicism. Although the family lived in rather poor circumstances, Jens Mommsen aroused his children’s interest in the antique classics at an early age. After initial private lessons, Theodor Mommsen visited the Christianeum in Altona from October 1834 and began law studies at the University of Kiel in May 1838. In 1843, he received his doctorate in Kiel from Georg Christian Burchardi with the thesis Ad legem de scribis et viatoribus et De auctoritate. Although he was actually a lawyer, from then on he devoted himself almost exclusively to ancient history based on his studies of Roman law, which only emerged around this time as a discipline in its own right.

Academic Career…

Mommsen was aiming for an academic career, but first had to earn his living as a substitute teacher at two girls’ boarding schools run by his aunts in Altona. In 1844 he received a Danish travel scholarship (the Duchy of Schleswig was at that time in personal union with Denmark) and visited first France, then especially Italy, where he began his occupation with Roman inscriptions. He contacted the Archaeological Institute and planned a collection of all known Latin inscriptions, which, unlike earlier corpora, was based on the autopsy principle. As a first step, Mommsen collected the inscriptions of the then Kingdom of Naples.

…and Political Engagement

“It is the deepest and most glorious effect of the artistic arts and above all of poetry that they lift up the barriers of the bourgeois communities and create from the tribes a people, from the peoples a world.”

– Theodor Mommsen, Roman History, Volume 1

In 1847 Mommsen returned to Germany, but had to work as a teacher again for the time being. During the March Revolution of 1848 he became a journalist in Rendsburg and vigorously defended his liberal convictions. In the autumn of that year he was appointed extraordinary professor of law in Leipzig and was finally able to embark on a scientific career. He began an extensive publishing career, but also remained politically active, together with his friends and fellow professors Moriz Haupt and Otto Jahn. Because of their participation in the Saxon May Uprising in 1849, the three were accused and dismissed from university service in 1851. In the same year Mommsen was appointed to a chair of Roman law in Zurich, which he took up in 1852. In 1854, he took over a professorship in Breslau. In 1858 Mommsen’s most fervent wish came true: he was appointed to a research professorship at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin and in 1861 received a chair for Roman Archaeology at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, where he lectured until 1885.

Honors and Memorable Students

Mommsen was a member of the Königlich Sächsische Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Leipzig and from 1852 a foreign member of the Königliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, from 1872 of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, from 1876 socio straniero of the Accademia dei Lincei in Rome and from 1895 a foreign member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Mommsen was unpopular with his students; he was considered a poor and imperious lecturer. Most of Mommsen’s students never managed to step out of the shadow of their overpowering teacher. Other younger scholars and some of Mommsen’s students, on the other hand, tried to emancipate themselves from their academic teacher. Of these, Max Weber is the most important, whom Mommsen considered his only worthy successor, but who turned to sociology before his doctorate.[1] Mommsen was highly honoured for his scientific achievements (Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts 1868, honorary citizenship of Rome). In the meantime he was also world-famous beyond the circles of experts. In 1902 Mommsen received the Nobel Prize for Literature for his major work, Roman History.

maps from Mommsen’s “Römische Geschichte”: “Latium” & “das Römische Reich und die Nachbarstaaten”

Roman History

“It goes without saying that Caesar was a passionate man, for without passion there is no genius; but his passion has never been more powerful than he.”

– Theodor Mommsen, Roman History, Volume 3

Mommsen wrote over 1500 scientific studies and treatises on various research topics, especially on the history and legal system of the Roman Empire from early times to late antiquity. His most famous publication is Roman History, written at the beginning of his career. It appeared in three volumes from 1854 to 1856 and described the history of Rome up to the end of the Roman Republic and the reign of Gaius Iulius Caesar, [2] whom Mommsen represented as a brilliant statesman. Thus Mommsen shaped the highly positive image of Caesar in German research for almost a century. In his terminology, Mommsen compares the political conflicts of the late republic in particular with the political developments of the 19th century (nation state, democracy). The committedly written work, although outdated in many respects, is considered a classic of historiography, not least because of its literary quality. Mommsen, whose scientific approach to antiquity changed greatly in later years, never wrote a continuation of Roman history into the imperial period; only transcripts of his lectures on Roman imperial history were published (only 1992). In 1885, Volume 5 of Roman History was published, a systematic account of the Roman provinces in the early Roman Empire. The three-volume (1871-1888) systematic presentation of Roman constitutional law in his work Römisches Staatsrecht (Roman Constitutional Law) is still of great importance for research into ancient history and legal history. He also wrote a work on Roman criminal law (Römisches Strafrecht, 1899).

Mammoth Projects

At the Berlin Academy, where he was secretary of the Historical-Philological Class from 1874 to 1895, Mommsen organised numerous large scientific projects, above all source editions. Mommsen had already conceived the collection of all known ancient Latin inscriptions (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum) at the beginning of his scientific career, when he published the inscriptions of the Kingdom of Naples as a model (1852). The complete Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum was to contain 16 volumes, 15 of which were published during Mommsen’s lifetime, five of which were written by Mommsen himself. In contrast to earlier collections, the basic principle for the edition was the autopsy principle, in which all preserved inscriptions were checked in the original. Under the direction of Mommsen, the Reichs-Limeskommission began its work in 1892, the aim of which was to determine the exact course and location of the forts of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes. The research reports on the excavations filled fourteen volumes and are still regarded today as a unique pioneering achievement in the reappraisal of Germanic-Roman history. Mommsen also published the imperial collections of laws Corpus Iuris Civilis and Codex Theodosianus, which were fundamental to Roman law.

Politics

In the so-called Berlin Anti-Semitism Controversy of 1879/1880 he turned against his historian colleague Heinrich von Treitschke,[3] who had coined the slogan “The Jews are our misfortune” and thus made Jewish hatred socially acceptable in Mommsen’s eyes. In 1890 Mommsen was one of the leading founders of the Association for the Defence against Anti-Semitism. The Freie Wissenschaftliche Vereinigung elected him an honorary member in 1887. Mommsen was an indefatigable worker who rose at five to do research in his library. People often saw him reading whilst walking in the streets. Mommsen had sixteen children with his wife Marie. He died on 1 November 1903 in Charlottenburg, Kingdom of Prussia, at age 85.

Okko Behrends, The Spirit of Roman Law, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Max Weber – one of the Founders of Sociology, SciHi Blog

- [2] Veni, Vidi, Vici – according to Julius Caesar, SciHi Blog

- [3] The Political Thought of Heinrich von Treitschke, SciHi Blog

- [4] Works written by or about Theodor Mommsen at Wikisource

- [5] Works by or about Theodor Mommsen at Internet Archive

- [6] The Nobel Prize Bio on Mommsen

- [7] Theodor Mommsen History of Rome

- [8] Theodor Mommsen at Wikidata

- [9] Okko Behrends, The Spirit of Roman Law, Cornell University @ youtube

- [10] Carter, Jesse Benedict. “Theodor Mommsen,” The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. XCIII, 1904.

- [11] Römische Geschichte (Roman History) at German Project Gutenberg: E-Text of Vol. 1 – 5 & 8 (vol. 6 & 7 do not exist) in German

- [12] Timeline for Theodor Mommsen, via Wikidata