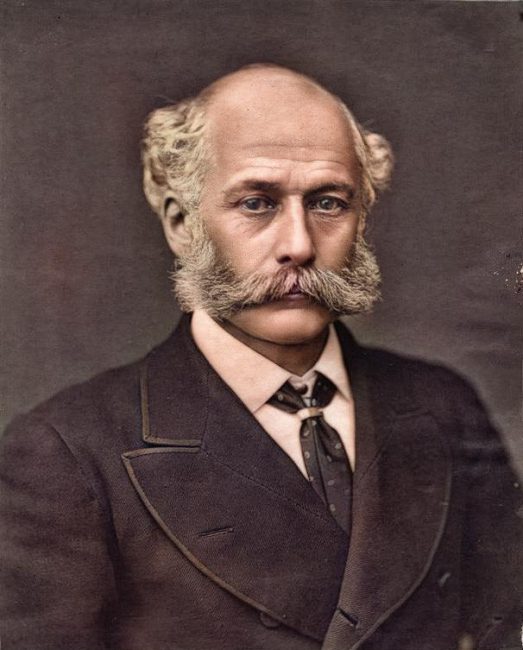

Joseph Bazalgette (1819-1891)

On March 28, 1819, British civil engineer Joseph William Bazalgette was born. As chief engineer of London‘s Metropolitan Board of Works Bazalgette‘s major achievement was the creation in response to the Great Stink of 1858 of a sewer network for central London which was instrumental in relieving the city from cholera epidemics, while beginning the cleansing of the River Thames.

From Railway Projects to London’s Sewers

Joseph William Bazalgette was mainly educated at home and was employed to Sir John MacNeill where he started working on railway projects as well as sea embankments in Ireland. In 1842, Bazalgette set up a consulting practice. Due to the railway boom at the time, Bazalgette received much work, probably too much. In 1848 the engineer suffered a nervous breakdown and was unable to work for a year. During Bazalgette’s time of recovery, London’s Metropolitan Commission of Sewers ordered that all cesspits should be closed and that house drains should connect to sewers and empty into the Thames.

Cholera Epidemics

As a result, a cholera epidemic of 1848 and 1849 killed more than 14.000 Londoners. Bazalgette was appointed assistant surveyor to the Commission in 1849, taking over as Engineer in 1852. Already one year later, another cholera epidemic killed more than 10.000 people. Back then it was generally believed that cholera was caused by foul air while Dr John Snow had earlier advanced a different (correct) explanation that cholera was spread by contaminated water. His view was not generally accepted.[6]

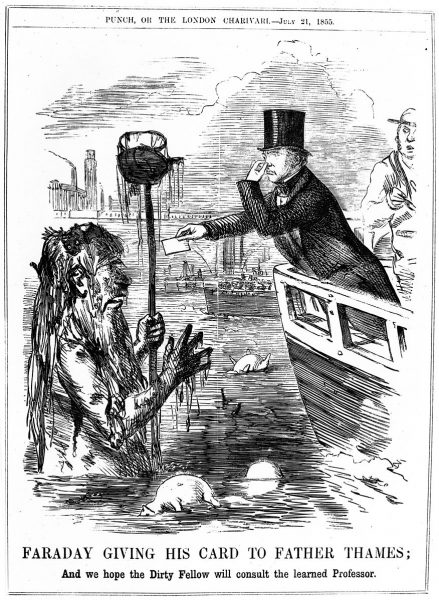

Michael Faraday giving his card to Father Thames

The London Sewers

Starting from the 17th century, brick sewers were built in London and by 1856, over a hundred sewers were constructed in London, and at that date the city had around 200,000 cesspits and 360 sewers. However, some cesspits leaked methane and other gases, which often caught fire and exploded while numerous sewers were in a poor state of repair. By 1858 many of the city’s medieval wooden water pipes were being replaced with iron ones. This, combined with the introduction of flushing toilets and the rising of the city’s population from just under one million to three million, led to more water being flushed into the sewers, along with the associated effluent. The outfalls from factories, slaughterhouses and other industrial activities put further strain on the already failing system. Much of this outflow either overflowed, or was discharged directly, into the Thames.

The Great Stink

Michael Faraday [7] described the situation in a way that “Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface, even in water of this kind. … The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water; it was the same as that which now comes up from the gully-holes in the streets; the whole river was for the time a real sewer”. By 1857, the extreme smell caused the government to pour chalk lime, chloride of lime and carbolic acid into the waterway to ease the stench.

“The Silent Highwayman” (1858). Death rows on the Thames, claiming the lives of victims who have not paid to have the river cleaned up.

Enclosing the Sewers

Joseph William Bazalgette had already been appointed chief engineer of the Commission’s successor, the Metropolitan Board of Works, in 1856. In 1858, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert [8] attempted to take a pleasure cruise on the Thames, but returned to shore within a few minutes because the smell was so terrible. The press soon began calling the event “The Great Stink“. At the height of the stink, between 200 and 250 tons of lime were being used near the mouths of the sewers that discharged into the Thames, and men were employed spreading lime onto the Thames foreshore at low tide. Then, Parliament passed an enabling act, in spite of the colossal expense of the project, and Bazalgette’s proposals to revolutionize London’s sewerage system began to be implemented. The expectation was also that enclosed sewers would eliminate the stink (‘miasma’), and that this would then reduce the incidence of cholera.

Construction of the sewers in 1859, near Old Ford, Bow in East London

Bazalgette’s Plan

Bazalgette’s plans for the 1,800 km of additional street sewers which would feed into 132 km of main interconnecting sewers, were put out to tender between 1859 and 1865. The provision of an integrated and fully functioning sewer system for the capital, together with the associated drop in cholera cases, led the historian John Doxat to state that Bazalgette “probably did more good, and saved more lives, than any single Victorian official“. Joseph William Bazalgette continued his work for the city of London until 1889 during which time he replaced three of London’s bridges, Putney, Hammersmith, and Battersea.

Michael Rossi, Pandemics in History: Cholera and the Rise of Public Health, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Joseph Bazalgette at Science Museum

- [2] Joseph Bazalgette at Britannica

- [3] The Great Stink at the River Thames Information Website

- [4] The Great Stink at Crossness

- [5] Joseph Balzagette at Wikidata

- [6] John Snow – Tracing the Source of the London Cholera Outbreak, SciHi Blog

- [7] A Life of Discoveries – the great Michael Faraday, SciHi Blog

- [8] Victoria and Albert – A Royal Wedding, SciHi Blog

- [9] Michael Rossi, Pandemics in History: Cholera and the Rise of Public Health, University of Chicago Professional Education @ youtube

- [10] Beare, Thomas Hudson (1901). . Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Because I had focused on Crossness (1865), there were many parts of the Bazalgette story that was omitted. “Due to the railway boom at the time, the engineer suffered a nervous breakdown In 1848 and was unable to work for a year. During Bazalgette’s time of recovery, London’s Metropolitan Commission of Sewers ordered that all cesspits should be closed and that house drains should connect to sewers and empty into the Thames”. I wonder what difference this absence ( i.e recovery period) made to the decision making.

Thanks for the link

Hels

Art and Architecture, mainly

https://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com/2009/05/crossness-london-amazing-victorian.html