Gaius Sallustius Crispus (86 BC – 35 BC)

On October 1, 86 BC, Roman historian, politician Gaius Sallustius Crispus was born. Sallustius is the earliest known Roman historian with surviving works to his name, of which we have Catiline‘s War, The Jugurthine War, and the Histories (of which only fragments survive). The Bellum Catiline, Sallustius’ first published work, contains the history of the memorable year 63 and the story of Catiline’s Conspiracy. Back in school I already made the acquaintance of Sallustius with his account of Catiline’s Conspiracy soon after Cicero‘s book. While Cicero‘s report had the much better beginning – “Quo usque tandem abutere patientia nostra, Catilina (For how long, Catiline, will you continue to waste our patience…)”, for me Sallusius’t account was much better comprehensible, since he had used a much more direct language and less fine bonmots [1,2].

“Nam divitiarum et formae gloria fluxa atque fragilis est, virtus clara aeternaque habetur.”

(For the fame of riches and beauty is fickle and frail, while virtue is eternally excellent.)

– Gaius Sallustius Crispus, Bellum Catilinae

Gaius Sallustius Crispus – Early Years

Sallustius was probably born in Amiternum in Central Italy, also the exact date of his birth is more or less , while 86 BC is widely used. Sallustius’ family was Sabine and probably belonged to the local aristocracy. They belonged to the equites and had a full Roman citizenship, but Sallustius was the only member known to have served in the Roman Senate. Thus, he embarked on a political career as a novus homo (“new man”); that is, he was not born into the ruling class, which was an accident that influenced both the content and tone of his historical judgments.[3] Only little is known of Sallustius’ early career, but he probably gained some military experience, perhaps in the east in the years from 70 to 60 BC. His first political office, which he held in 52, was that of a tribune of the plebs. The office, originally designed to represent the lower classes, by Sallustius’ time had developed into one of the most powerful magistracies. The evidence that Sallustius held a quaestorship, an administrative office in finance, sometimes dated about 55, is unreliable.

A Public Career

From the beginning of his public career, Sallustius operated as a decided partisan of Julius Caesar [4], to whom he owed such political advancement as he attained. Because of electoral disturbances in 53 BC, there were no regular government officials other than the tribunes. The year opened in violence that led to the murder of Clodius Pulcher, a notorious demagogue and candidate for the praetorship, by a gang led by Titus Annius Milo, a candidate for consul. In the trial that followed, Cicero defended Milo, while Sallustius and his fellow tribunes harangued the people in speeches attacking Cicero.[3] In 50 BC, the censor Appius Claudius Pulcher removed him from the Senate on the grounds of gross immorality (probably really because of his opposition to Milo and Cicero). In the following year, perhaps through Caesar’s influence, he was reinstated. In the late summer 47 BC a group of soldiers rebelled near Rome, demanding their discharge and payment for service. Sallustius as praetor designatus was sent to persuade the soldiers with several other senators, but the rebels killed two senators, while Sallustius narrowly escaped death.

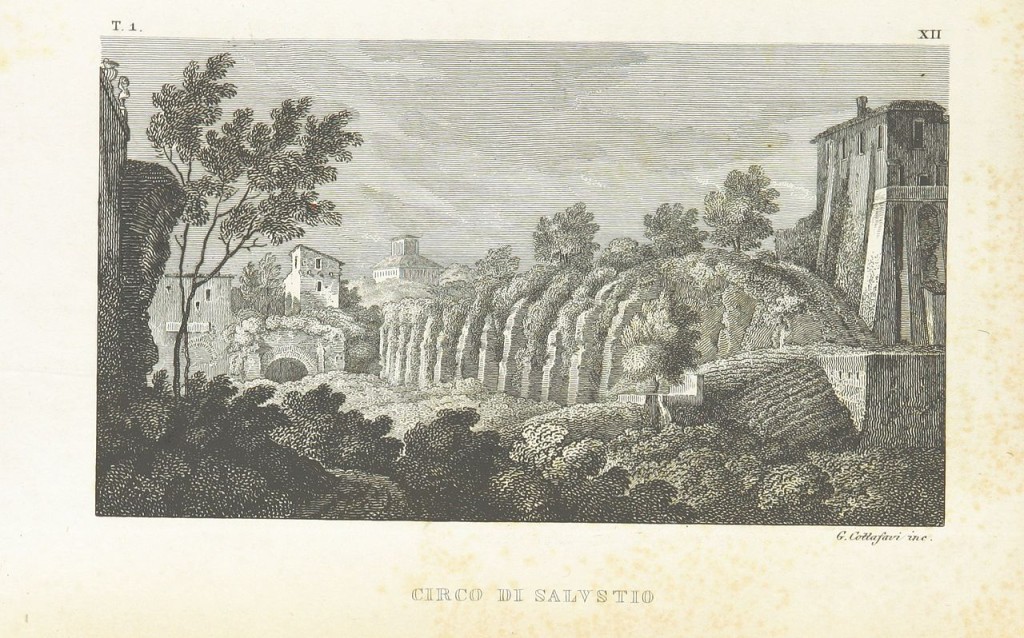

Rome, ancient and modern, and its environs (The British Library, 1842)

Invective against Sallustius

In 46 BC, he served as a praetor and accompanied Caesar in his African campaign, which ended in the decisive defeat of the remains of the Pompeian war party at Thapsus. Sallustius did not participate in military operations directly, but he commanded several ships and organized supply through the Kerkennah Islands. As a reward for his services, Sallustius gained appointment as governor of the province of Africa Nova. Upon returning to Rome, Sallustius was accused of extortion and of plundering his province, but through Caesar’s intervention he was never brought to trial according to the “Invective Against Sallust,” as reported by Dio Cassius.[3]

The Horti Sallustiani

After the death of Caesar in 44 BC, Sallustius then purchased and began laying out in great splendour the famous gardens on the Quirinal known as the Horti Sallustiani or Gardens of Sallustius. These gardens would later belong to the emperors. Sallustius then retired from public life and devoted himself to historical literature, and further developed his Gardens, upon which he spent much of his accumulated wealth. Sallustius died in 35 BC, leaving his house and gardens to his sister’s grandson. These afterward became the favorite resort of Nero, Nerva, and other Roman emperors.[5] The gardens remained an imperial resort until they were sacked in 410 AD by the Goths under Alaric, who entered the city at the gates of the Horti Sallustiani.

Catiline’s War

His first monograph, Bellum Catilinae (43–42 BC; Catiline’s War), deals with corruption in Roman politics by tracing the conspiracy of Catiline, a ruthlessly ambitious patrician who had attempted to seize power in 63 BC after the suspicions of his fellow nobles and the growing mistrust of the people prevented him from attaining it legally.[1,3] In Sallustius’ view, Catiline’s crime and the danger he presented were unprecedented. While he inveighs against Catiline’s depraved character and vicious actions, he does not fail to state that the man had many noble traits, indeed all that a Roman man needed to succeed.[6] Sallustius describes the course of the conspiracy and the measures taken by the Senate and Cicero, who was then consul.

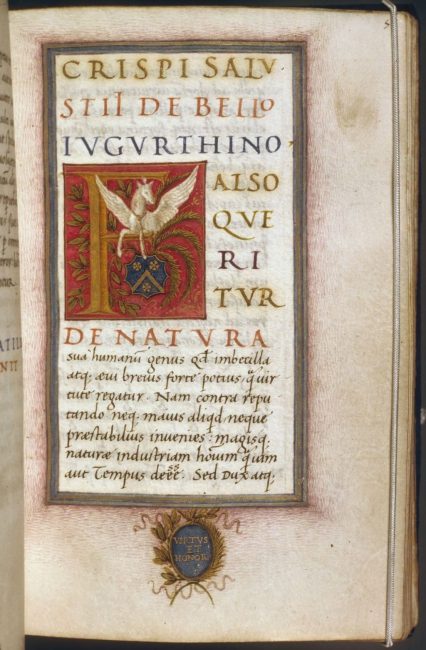

c. 1490 manuscript for De Bello Jugurthino

The Jugurthine War

“Nam concordia parvae res crescunt, discordia maxumae dilabuntur.”

(For harmony makes small states great, while discord undermines the mightiest empires.)

– Gaius Sallustius Crispus, Bellum Jugurthinum

Sallustius` Bellum Jugurthinum (41–40 BC; The Jugurthine War) is a brief but picturesque account of the war against Jugurtha in Numidia from c. 112 BC to 105 BC. There, he explored in greater detail the origins of party struggles that arose in Rome when war broke out against Jugurtha, the wily Numidian prince, who bribed Roman senators and generals alike. The true value of this monograph lies in the introduction of Marius and Sulla to the Roman political scene and the beginning of their rivalry. Sallustius` time as governor of Africa Nova ought to have let the author develop a solid geographical and ethnographical background to the war.

The Histories

Sallustius` last work was a history in five books, Historiarum Libri Quinque, embracing the important period between Sulla’s death, 78 BC, and Cicero’s praetorship in 67 BC. Of this, unfortunately, we cannot judge, as only four speeches and two letters remain. Sallustius’ style differs from the writings of his contemporaries — Caesar and especially Cicero. It is characterized by brevity and by the use of rare words and turns of phrase. As a result, his works are very far from the conversational Latin of his time. Sallustius’ narratives were enlivened with speeches, character sketches, and digressions, and, by skillfully blending archaism and innovation.[3] This picturesqueness, vigor, and intensity of Sallustius’ style were greatly admired by his countrymen.[5]

Gale Trimble, Sallust’s Characterisation of Catiline [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Quo usque tandem, Catilina – Cicero and the Catilinarian Conspiracy, SciHi Blog, Oct 21, 2013.

- [2] Marcus Tullius Cicero – Truly a Homo Novus, SciHi blog, Jan 3, 2015.

- [3] Sallust – Roman Historian, at Britannica Online

- [4] Veni, vidi, vici – according to Iulius Caesar, SciHi Blog, Aug 2, 2012.

- [5] “Introduction”, Sallust’s Catiline, ed. Jared W. Scudder, Allyn & Bacon: Boston, 1900. via The Society for Ancient Languages

- [6] Sallust, from biographybase

- [7] Works by Sallust at project Gutenberg

- [8] Sallust at Wikidata

- [9] Works by or about Sallusti at Internet Archive

- [10] Gale Trimble, Sallust’s Characterisation of Catiline, Tom Mackenzie @ youtube

- [11] Earl, DC (1966). “The Early Career of Sallust”. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 15 (3): 302–311.

- [12] MacKay, LA (1962). “Sallust’s “Catiline”: Date and Purpose”. Phoenix. 16 (3): 181–194.

- [13] Osmond, Patricia J (1995). ““Princeps Historiae Romanae”: Sallust in Renaissance Political Thought”. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 40: 101–143.

- [14] Woodman, AJ (2008). Introduction. Catiline’s War, The Jugurthine War, Histories. By Sallust. Translated by Woodman, AJ. Penguin.

- [15] Timeline of Latin Historians, via Wikidata and DBpedia