Two of the Forty-Seven Rōnin: Horibe Yahei and his adopted son, Horibe Yasubei.

In Genroku 15, on the 14th day of the 12th month (元禄十五年十二月十四日, Tuesday, January 30, 1703), in revenge for the death of their prince Asano, 47 Ronin invaded the house of the Japanese Shogunate official Kira Yoshihisa in Edo and killed him and his male followers. The story of the 47 Ronin is one of the most celebrated in the history of the samurai. Described by Japanese historians as a ‘National Legend’, the revenge of the 47 Ronin is the ultimate expression of the samurai code of honor, Bushido.

The Akō Incident

The event is known in Japan as the Akō incident (赤穂事件 Akō jiken), sometimes also referred to as the Akō vendetta. The participants in the revenge are called the Akō-rōshi (赤穂浪士) or Shi-jū-shichi-shi (四十七士) in Japanese, and are usually referred to as the “Forty-seven Rōnin” or “Forty-seven leaderless samurai” in English. Literary accounts of the events are known as the Chūshingura (忠臣蔵 The Treasury of Loyal Retainers).

In 1701, two daimyōs (princes), Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori, the young daimyō of the Akō Domain, and Lord Kamei Korechika of the Tsuwano Domain, were ordered to arrange a fitting reception for the envoys of the Emperor at Edo Castle, during their sankin kōtai service to the Shogun. Asano and Kamei were to be given instruction in the necessary court etiquette by Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a powerful official in the hierarchy of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s shogunate. He became upset at them, allegedly either because of the insufficient presents they offered him or because they would not offer bribes as he wanted. By some accounts, it also appears that Asano may have been unfamiliar with the intricacies of the Shogunate court and failed to show proper level of deference to Kira. Whether Kira treated them poorly, insulted them, or failed to prepare them for fulfilling specific bakufu duties, offence was taken.

The Insult of Asano

Initially, Asano bore all this stoically, while Kamei became enraged and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, Kamei’s quick-thinking counselors averted disaster for their lord and clan by quietly giving Kira a large bribe; Kira thereupon began to treat Kamei nicely, which calmed Kamei. However, Kira allegedly continued to treat Asano harshly, because he was upset that the latter had not emulated his companion. Finally, Kira insulted Asano, calling him a country boor with no manners, and Asano could restrain himself no longer. At the Matsu no Ōrōka, the main grand corridor that interconnects the Shiro-shoin (白書院) and the Ōhiroma of the Honmaru Goten (本丸御殿) residence, Asano lost his temper and attacked Kira with a dagger, wounding him in the face with his first strike; his second missed and hit a pillar.

Kira’s wound was hardly serious, but the attack on a shogunate official within the boundaries of the shogun’s residence was considered a grave offence. The daimyō of Akō had removed his dagger from its scabbard within Edo Castle, and for that offence, he was ordered to kill himself by seppuku. Asano’s goods and lands were to be confiscated after his death, his family was to be ruined, and his retainers were to be made rōnin (leaderless). This news was carried to Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, Asano’s principal counsellor, who took command and moved the Asano family away, before complying with bakufu orders to surrender the castle to the agents of the government.

The 47 Ronin

Of Asano’s over 300 men, 47, especially their leader Ōishi, refused to allow their lord to go unavenged, even though revenge had been prohibited in the case. They banded together, swearing a secret oath to avenge their master by killing Kira.However, Kira was well guarded, and his residence had been fortified to prevent just such an event. The rōnin saw that they would have to put him off his guard before they could succeed. To quell the suspicions of Kira and other shogunate authorities, they dispersed and became tradesmen and monks. Ōishi went to his loyal wife and divorced her so that no harm would come to her when the rōnin took revenge. Ōishi began to act oddly and very unlike the composed samurai. He frequented geisha houses, drank nightly, and acted obscenely in public.

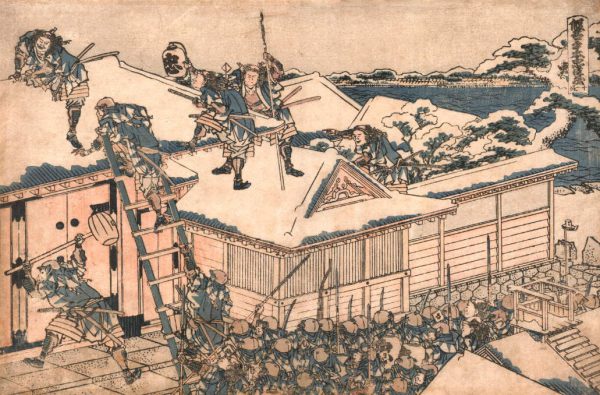

The rōnin attack the principal gate of Kira’s mansion, woodcut by Hokusai

Kira’s agents reported all this to Kira, who became convinced that he was safe from Asano’s retainers, that they must all be bad samurai indeed, without the courage to avenge their master after a year and a half. Thinking them harmless and lacking funds from his “retirement”, he then reluctantly let down his guard.

The Attack

After two years, when Ōishi was convinced that Kira was thoroughly off his guard, and everything was ready, he fled from Kyoto, avoiding the spies who were watching him, and the entire band gathered at a secret meeting place in Edo to renew their oaths. In Genroku 15, on the 14th day of the 12th month early in the morning in a driving wind during a heavy fall of snow, Ōishi and the ronin attacked Kira Yoshinaka’s mansion in Edo. According to a carefully laid-out plan, they split up into two groups and attacked, armed with swords and bows. Once Kira was dead, they planned to cut off his head and lay it as an offering on their master’s tomb. They would then turn themselves in and wait for their expected sentence of death.

Ōishi had four men scale the fence and enter the porter’s lodge, capturing and tying up the guard there.[19] He then sent messengers to all the neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers, but retainers out to avenge the death of their master, and that no harm would come to anyone else: the neighbors were all safe. One of the ronin climbed to the roof and loudly announced to the neighbors that the matter was an act of revenge. The neighbors, who all hated Kira, were relieved and did nothing to hinder the raiders.

Kira, in terror, took refuge in a closet in the veranda, along with his wife and female servants. The rest of his retainers, who slept in barracks outside, attempted to come into the house to his rescue. Eventually, after a fierce struggle, the last of Kira’s retainers was subdued; in the process, the ronin killed 16 of Kira’s men and wounded 22, including his grandson. Of Kira, however, there was no sign.

A renewed search disclosed an entrance to a secret courtyard hidden behind a large scroll; the courtyard held a small building for storing charcoal and firewood, where two more hidden armed retainers were overcome and killed. A search of the building disclosed a man hiding; he attacked the searcher with a dagger, but the man was easily disarmed. The ronin gathered, and Ōishi, with a lantern, saw that it was indeed Kira — as a final proof, his head bore the scar from Asano’s attack.

The Revenge

At that, Ōishi went on his knees, and in consideration of Kira’s high rank, respectfully addressed him, telling him they were retainers of Asano, come to avenge him as true samurai should, and inviting Kira to die as a true samurai should, by killing himself. However, no matter how much they entreated him, Kira crouched, speechless and trembling. At last, seeing it was useless to ask, Ōishi ordered the other ronin to pin him down, and killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger. On arriving at the temple, the remaining 46 rōnin washed and cleaned Kira’s head in a well, and laid it, and the fateful dagger, before Asano’s tomb.

The shogunate officials in Edo were in a quandary. The samurai had followed the precepts by avenging the death of their lord; but they had also defied the shogunate authority by exacting revenge, which had been prohibited. In addition, the shogun received a number of petitions from the admiring populace on behalf of the rōnin. As expected, the rōnin were sentenced to death for the murder of Kira; but the Shogun finally resolved the quandary by ordering them to honorably commit seppuku instead of having them executed as criminals.

The End of the Ronin

Each of the 46 rōnin killed themselves in Genroku 16. This has caused a considerable amount of confusion ever since, with some people referring to the “forty-six rōnin”; this refers to the group put to death by the shogun, while the actual attack party numbered forty-seven. The forty-seventh rōnin, identified as Terasaka Kichiemon, eventually returned from his mission and was pardoned by the shogun (some say on account of his youth). He lived until the age of 87, dying around 1747, and was then buried with his comrades.

The tragedy of the Forty-seven Rōnin has been one of the most popular themes in Japanese art, and has lately even begun to make its way into Western art. The incident immediately inspired a succession of kabuki and bunraku plays and even an opera. The play has been made into a movie at least six times in Japan. The 1962 film version directed by Hiroshi Inagaki, Chūshingura, is most familiar to Western audiences. In it, Toshirō Mifune appears in a supporting role as spearman Tawaraboshi Genba. Mifune was to revisit the story several times in his career. In 1971 he appeared in the 52-part television series Daichūshingura as Ōishi, while in 1978 he appeared as Lord Tsuchiya in the epic Swords of Vengeance.

For many years, the version of events retold by A. B. Mitford in Tales of Old Japan (1871) was considered authoritative. The sequence of events and the characters in this narrative were presented to a wide popular readership in the West. Mitford invited his readers to construe his story of the Forty-seven Rōnin as historically accurate; and while his version of the tale has long been considered a standard work, some of its precise details are now questioned.

The History of the 47 Ronin and Reasons Why They’re So Famous in Japan, [5]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Yamamoto Tsunetomo and the Way of the Samurai, SciHi Blog 12. June 2013

- [2] Chushingura and the Samurai Tradition – Comparisons of the accuracy of accounts by Mitford, Murdoch and others, as well as much other useful material, by noted scholars of Japan

- [3] Chūshingura: Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki – at IMDB

- [4] The 47 Ronin at Wikidata

- [5] The History of the 47 Ronin and Reasons Why They’re So Famous in Japan, Let’s ask Shogo | Your Japanese friend in Kyoto @ youtube

- [6] Benesch, Oleg (2014). Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- [7] Mitford, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford, Lord Redesdale (1871). Tales of Old Japan. London: University of Michigan.

- [8] Harper, Thomas (2019). 47: The True Story of the Vendetta of the 47 Ronin from Akô . Leete’s Island Books.

- [9] Henry D. Smith II, The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh Ronin and the Chushingura Imagination, Japan Review, 2004, 16:3–65

- [10] Timeline of Suicides by Seppuku, via Wikidata and DBpedia