James Brindley (1717 – 1772)

On September 30, 1772, English engineer and pioneer canal builder James Brindley probably passed away. One of the most notable engineers of the 18th century, he is best known for the construction of the first English canal of major economic importance.

James Brindley – Early Years

James Brindley, was born in 1716 in Tunstead, Derbyshire, the son of a wealthy farming and artisan family. He grew up in the then undeveloped region of the Peak District and received little formal schooling. It is assumed that he was mostly educated by his mother. When Brindley was 17 years old, he was apprenticed to a millwright in Sutton, Macclesfield and soon showed exceptional skill and ability. After completing his duties, James Brindley set up a business as a wheelwright in Leek, Staffordshire and expanded his business quickly.

Brindley established a reputation for ingenuity and skill at repairing many different kinds of machinery. In 1750 he expanded his business by renting a millwright’s shop in Burslem from the Wedgwoods who became his lifelong friends. He soon established a reputation for ingenuity and skill at repairing many different kinds of machinery. In 1752 he designed and built an engine for draining a coal mine, the Wet Earth Colliery at Clifton in Lancashire. Three years later he built a machine for a silk mill at Congleton.

The Bridgewater Canal

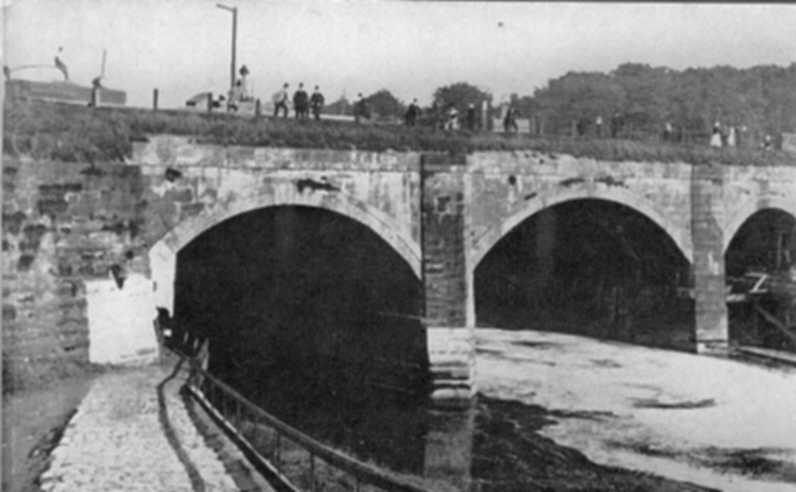

The 3rd Duke of Bridgewater recognized Brindley’s reputation who was looking for a way to improve the transport of coal from his coal mines at Worsley to Manchester. During the end of the 1750s, the Duke commissioned the construction of a canal to do just that. The resulting Bridgewater Canal, opened in 1761, is often regarded as the first British canal of the modern era, even though there is a dispute on whether the Sankey Canal was the first or not. Brindley was commissioned as the consulting engineer and, although he has often been credited as the genius behind the construction of the canal, it is now thought that the main designers were probably the Duke himself, who had some engineering training, and his land agent and engineer John Gilbert. Brindley was engaged, at the insistence of Gilbert, to assist with particular problems such as the Barton Aqueduct. This most impressive feature of the canal carried the canal at an elevation of 13 metres over the River Irwell at Barton.

Barton Aqueduct, shortly before its demolition, 1891

Puddle Clay

James Brindley’s technique minimised the amount of earth moving by developing the principle of contouring. He preferred to use a circuitous route that avoided embankments, and tunnels rather than cuttings. Though this recognised the primitive methods of earth-moving available at the time, it meant that his canals were often much longer than a more adventurous approach would have produced. But his greatest contribution was the technique of puddling clay to produce a watertight clay-based material, and its use in lining canals. Puddle clay was used extensively in UK canal construction in the period starting shortly after his death. Starting about 1840 puddle clay was used more widely as the water-retaining element (or core) within earthfill dams, particularly in the Pennines.

Later Years

Brindley hoped to link England’s four great rivers, the River Mersey, River Trent, Severn and Thames, with canals (the “Grand Cross” plan). The Trent and Mersey Canal was built first, then the Chester Canal from 1772. However, coal transport from the Midlands to the Thames did not function until 1790, long after Brindley’s death. In total, throughout his life Brindley built 587 km of canals and many watermills, including the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal the Coventry Canal, the Oxford Canal and numerous others, and he also constructed the watermill at Leek, now the Brindley Water Museum.

In 1771, work had begun on the Chesterfield Canal, but while surveying a new branch of the Trent and Mersey between Froghall and Leek, Brindley was drenched in a severe rainstorm. It had happened many times before, but he was unable to dry out properly at the inn at which he was staying, and caught a chill. He became seriously ill and returned to his home at Turnhurst, Staffordshire, where Erasmus Darwin attended him and discovered that he was suffering from diabetes. James Brindley died at Turnhurst within sight of the unfinished Harecastle Tunnel on 27 September 1772.

Canal Irrigation System: Lecture-18, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Biography at the James Brindley Museum

- [2] James Brindley at Britannica

- [3] Smiles, Samuel (1864). James Brindley and the Early Engineers. London: John Murray.

- [4] Brindley Water Mill at Leek, Staffordshire

- [5] Christine Richardson: James Brindley: Canal Pioneer. 2004

- [6] James Brindley at Wikidata

- [7] Canal Irrigation System: Lecture-18, Water Resources Engineering, Ch-12 Civil Engineering and related subjects @ youtube

- [8] Malet, Hugh (1990). Coal Cotton and Canals. Radcliffe, Manchester: Neil Richardson.

- [9] Richardson, Christine (2004). James Brindley: Canal Pioneer.

- [10] Timeline of English Canal Engineers, via Wikidata and DBpedia