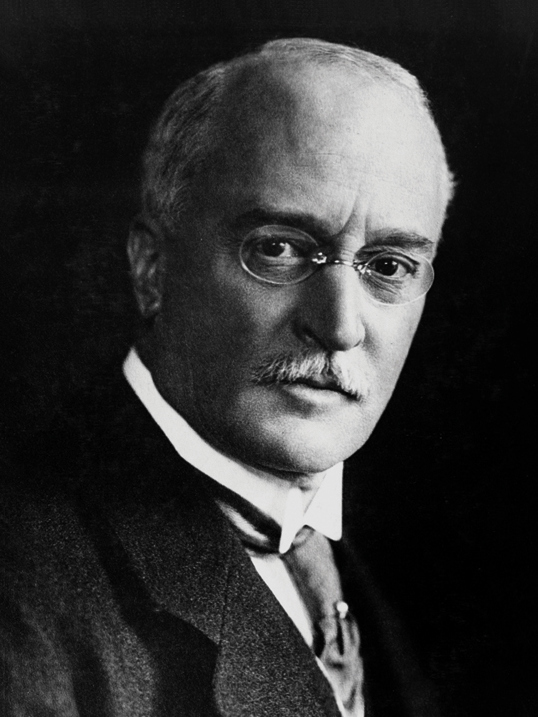

Rudolf Diesel (1858 – 1913)

On March 18, 1858, German inventor and mechanical engineer Rudolf Diesel was born, who invented the eponymous Diesel engine that uses the heat of compression to initiate ignition to burn the fuel.

“The automobile engine will come, and then I will consider my life’s work complete.”

– Rudolf Diesel

Early Years

Rudolf Diesel was born and grew up in Paris, known as an excellent student and awarded with a medal for his achievements at the age of only 12. Unfortunately, the Franco-Prussian War started in July 1870, wherefore all German citizens were expelled from France. The Diesel family left along with many other families Paris for London. Just a few months later, the young Diesel was sent to his relatives in Augsburg, where his father grew up. His uncle and aunt from then on took care of the boy, who soon after attending the industry and business related school his uncle taught at, decided to become an engineer himself. He finished school as the best of his class and enrolled at the Technical University of Munich, also shining with his brilliance. During his time at the University, Diesel gained practical experience at engineering works in Switzerland.

Rudolf Diesel on a 1958 German postage stamp

Carl von Linde and the Refrigeration Process

A great influence to Diesel was Carl von Linde, a German engineer responsible for developing refrigeration and gas separation technologies in the mid 19th and early 20th century. Linde was one of Diesel’s professors in Munich and he assisted Linde back in Paris with designs and construction methods of modern refrigeration and ice plants. Already married in the late 19th century, Diesel again left Paris, this time for Berlin to continue the work his former professor. Since he could not use the various patents, previously developed, Rudolf Diesel moved his field of research beyond refrigeration to work with steam. However, several experiments and a great explosion later, Diesel spent some time in the hospital, rethinking his methods.

The Compression-Ignition Engine

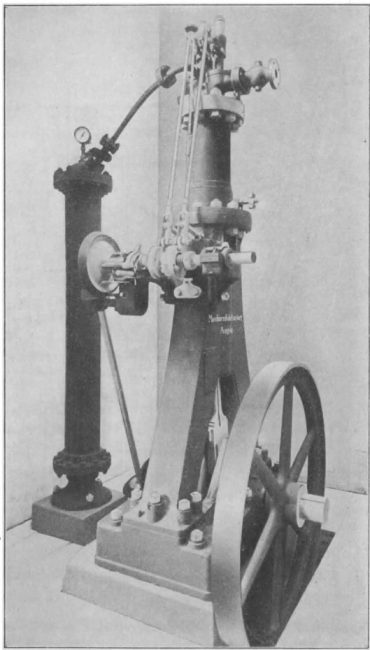

In the early 1820’s, Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot [7] demonstrated the famous ‘Carnot cycle‘, a theoretical thermodynamic cycle that shows the efficient cycle for converting an amount of thermal energy into work or creating a difference in temperature. Rudolf Diesel began designing an engine based on this principle. In 1886, Karl Benz [8] patented the motor car and a few years later, in 1893, Diesel published his work ‘Theorie und Konstruktion eines rationellen Wärmemotors zum Ersatz der Dampfmaschine und der heute bekannten Verbrennungsmotoren [Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat-engine to Replace the Steam Engine and Combustion Engines Known Today]‘, a milestone for the engineer on his way to develop the Diesel engine. Diesel was always longing for efficiency, and due to the fact that the steam engine wasted about 90% of the energy available in the fuel, he was even more driven to find his own solution. At one point he eventually managed to patent the design for his compression-ignition engine. Diesel was allowed to perform a series of tests on his machines at the MAN AG in Augsburg, Germany.

Diesels first experimental engine 1893

Later Years

Even though the Diesel engine as known by the inventor himself has been furtherly developed through the years, the heavy engine was soon used in submarines, ships, locomotives, trucks, and automobiles. The first Diesel engined ship ‘Seelandia‘ left the port of Copenhagen in 1912. Rudolf Diesel proved himself as a brilliant engineer and inventor during his whole life time, but he never really was as great in business relations. Under mysterious circumstances, Rudolf Diesel passed away on September 29, 1913. There are various theories to explain Diesel’s death. His biographers present a case for suicide, and clearly consider it most likely. Conspiracy theories suggest that various people’s business or military interests may have provided motives for homicide, however. Evidence is limited for all explanations.

Reginald Penner, Thermodynamics and Chemical Dynamics 131C. Lecture 13. The Carnot Cycle, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Rudolf Diesel, 1858 – 1913 / Biografie by Dieter Wunderlich [In German]

- [2] Rudolf Diesel at history.com

- [3] Diesel engine animated

- [4] . Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- [5] Thomas Newcomen and the Steam Engine, SciHi Blog

- [6] James Watt and the Steam Age Revolution, SciHi Blog

- [7] Carnot and Thermodynamics, SciHi Blog

- [8] Karl Benz and his Automobile Vehicle, SciHi Blog, January 29, 2018.

- [9] Rudolf Diesel at Wikidata

- [10] Reginald Penner, Thermodynamics and Chemical Dynamics 131C. Lecture 13. The Carnot Cycle, UCI Open @ youtube

- [11] Moon, John F. (1974), Rudolf Diesel and the Diesel Engine, London: Priory Press

- [12] “Diesel, Rudolf“. Collier’s New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- [13] Erwin Starke: Wie Rudolf Diesel starb In: Der Tagesspiegel vom 22. September 2013

- [14] Timeline of German inventors, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #31 | Whewell's Ghost