Robert Scott’s group on 17 January 1912, after they discovered Amundsen had reached the pole first.

On November 12, 1912, the frozen bodies of Robert Falcon Scott and his men are found on the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Robert F. Scott was a Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, 1901–04, and the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition, 1910–13. During this second venture, Scott led a party of five which reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, only to find that they had been preceded by Roald Amundsen‘s Norwegian expedition. On their return journey, Scott and his four comrades all died from a combination of exhaustion, starvation and extreme cold.

“We arrived within 11 miles of our old One Ton Camp with fuel for one hot meal and food for two days. For four days we have been unable to leave the tent – the gale howling about us. We are weak, writing is difficult, but for my own sake I do not regret this journey, which has shown that Englishmen can endure hardships, help one another, and meet death with as great a fortitude as ever in the past. We took risks, we knew we took them; things have come out against us, and therefore we have no cause for complaint, but bow to the will of Providence, determined still to do our best to the last.” – Robert Falcon Scott, March 29, 1912

Background Robert Falcon Scott

As it was a family tradition, Robert Scott and his brother Archibald were predestined for a life in the arms services. He started his naval career at the age of 13 as a cadet and was sent to South Africa in 1883 to join the flagship HMS Boadicea. During this trip, got to know a member of the Royal Geographical Society, who would later support Scott’s career. Scott became lieutenant in 1889 and applied for a torpedo training shortly after. About ten years after, Robert Scott learned about an Antarctic mission and volunteered to lead the expedition on June 11, 1899.

Discovery Expedition

The so called ‘Discovery Expedition‘ lasted from 1901 – 1904 and was indeed led by Robert Scott, who was promoted to the rank of commander just before the take off. The crew consisted of about 50 men, who had only little training and experience, which became dangerous in the Antarctic waters. Even though they took many skis with them, hardly anyone knew how to use them. Still, the crew fulfilled some scientific and exploration objectives. Robert Scott and two further crew members traveled towards the South Pole, which took them 850 km from the pole, until one man collapsed and the team was forced to return. The members improved their abilities and skills on the expedition and they managed to make significant biological, zoological, and geological findings. At the end, it took explosives to free the Discovery crew from the ice. When the expedition returned to Britain in September 1904, Scott became a popular hero.

Terra Nova Expedition

Around 1909, Robert Scott has already announced his plans for another Antarctic expedition, which later became known as the Terra Nova Expedition and started only one year after. He stated that next to several scientific goals, his main objective was to reach the South Pole but back then he did not know that Roald Amundsen followed the same goal. In October of the same year, he received a telegram, stating that Roald Amundsen was on his way to the South Pole as well. Already at the beginning, the expedition was trapped in pack ice and one of the motor sledges got lost.[4]

British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13. “Beautiful broken ice, reflections and Terra Nova. Jan. 7th 1911.”

The march to the South Pole began on 1 November 1911. Scott’s troop consisted of 16 men with snowmobiles, dogs and ponies for the transport of equipment and supplies. Their task was to enable a group of four men to advance to the South Pole. Scott had submitted his plans to the entire landing team, but had not made any concrete allocations of tasks. As a result, none of his companions knew who, apart from Scott, would belong to the South Pole group. Scott also sent some contradictory instructions to the base camp during the march, following the descriptions of some expedition participants and the representation of the majority of Scott’s biographers. Thus it remained apparently unclear whether the returning sled dog teams should primarily be spared for later scientific exploratory marches or whether they should be used to support the returning South Pole group in accordance with an order already written in advance by Scott. Finally, the team at Cape Evans avoided using the dogs to make a targeted attempt to save the South Pole group in distress.

The number of expedition participants marching southwards, who made slow progress due to adverse weather conditions and the early failure of snowmobiles and ponies, gradually decreased as individual support groups returned to base camp on schedule. On January 3, 1912 the last two groups of four finally reached a width of 87° 32′ S. Here Scott announced his decision to complete the way to the South Pole with five instead of four, together with Edward Wilson, Lawrence Oates, Edgar Evans and Henry Bowers, while Thomas Crean, William Lashly and Scott’s deputy Edward Evans had to give up their hopes and turn back to Cape Evans. Scott and his men finally reached the South Pole on January 18. At the destination they discovered that Roald Amundsen and four companions had arrived there five weeks earlier.

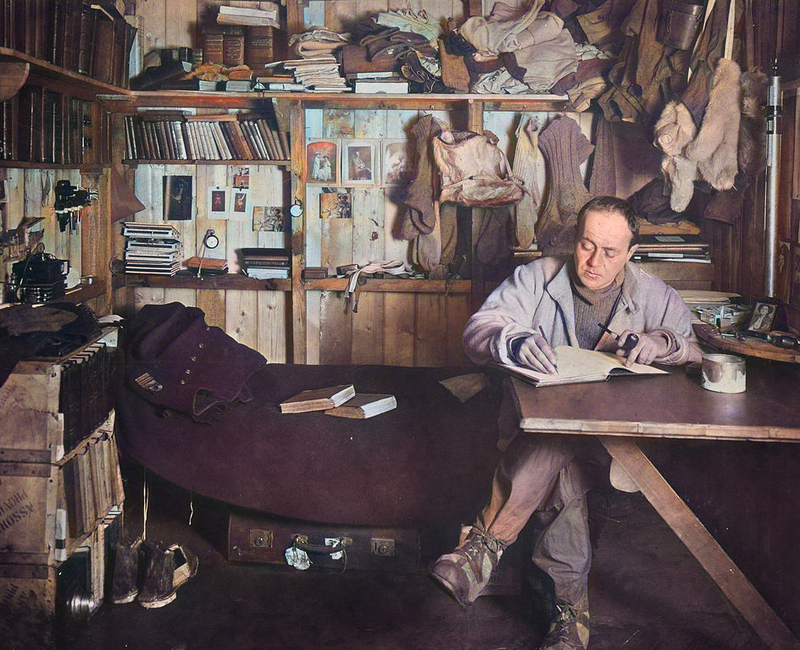

Captain Robert Falcon Scott writing in his diary, Cape Evans hut, 7th October 1911.

On 19 January 1912, the South Pole Group set out on the more than 1300 km long way back to the base camp at Cape Evans. At first they made good progress despite bad weather with icy temperatures. Already on 7 February they had covered 500 km to the upper edge of the Beardmore glacier in the Transantarctic Mountains and began the 160 km long descent across the glacier to the Ross Ice Shelf. However, according to Scott’s notes, Edgar Evans’ health had deteriorated since 23 January. On 17 February, Evans fell into a coma after another fall at the foot of the glacier and died the same day. In front of the other four men lay more than 660 km of distance over the Ross Ice Shelf, but the prospects deteriorated more and more. Plagued by stormy weather with sinking temperatures, severe frostbite, snow blindness, hunger and exhaustion, they fought their way only slowly. On March 17, Lawrence Oates, who was barely able to walk due to an old leg injury and frozen feet, put an end to his life.

The End of the Diary

Scott, Wilson and Bowers tried 20 km further north until they set up their last camp on March, 19. This was only 21 km south of the important One Ton depot, whose originally planned southern position the men had already crossed by 38 km. However, a persistent snowstorm kept them trapped in the tent. Records end on 29 March 1912. Scott is believed to have been the last of the three men to die on or shortly after the day of his last diary entry. A search party came across the last camp of the South Pole Group on 12 November 1912. The three dead men were covered with the outer tarpaulin and a high hill of snow was erected above them, flanked by two upright transport sleds, with a wooden cross made of ski boards on top.

Scott, Amundsen and Science: 100th Anniversary – Ed Larson (SETI Talks), [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] “Crucible of Ice” New York Times

- [2] Robert Falcon Scott at Britannica Online

- [3] Robert Falcon Scott at the Southpole Information Webpage

- [4] Amundsen’s South Pole Expedition, SciHi Blog

- [5] Ernest Shackleton and his South Pole Expeditions, SciHi Blog

- [6] The Nimrod Expedition and the Magnetic South Pole, SciHi Blog

- [7] Dr Livingstone, I presume?, SciHi Blog

- [8] Robert Falcon Scott at Wikidata

- [9] Scott, Amundsen and Science: 100th Anniversary – Ed Larson (SETI Talks), 2012, SETI Institute @ youtube

- [10] Crane, D. (2005). Scott of the Antarctic: A Life of Courage, and Tragedy in the Extreme South. London: HarperCollins.

- [11] Huxley, L., ed. (1913a). Scott’s Last Expedition, Volume I. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- [12] Jones, M. (2003). The Last Great Quest: Captain Scott’s Antarctic Sacrifice. Oxford University Press.

- [13] Solomon, S. (2001). The Coldest March: Scott’s Fatal Antarctic Expedition. London: Yale University Press.

- [14] Rees, J. (19 December 2004). “Ice in our Hearts”. The Daily Telegraph. London.

- [15] Timeline of Antarctic Explorers via DBpedia and Wikidata