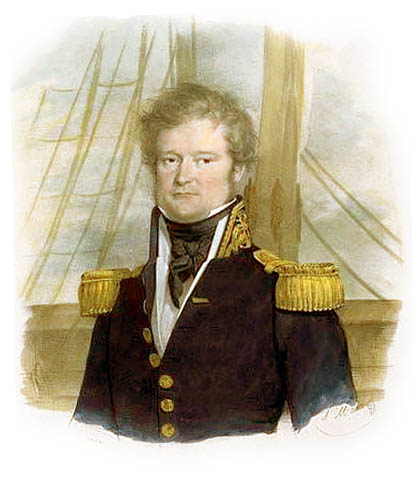

Jules Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842)

On May 8, 1842, French explorer, naval officer and rear admiral Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville passed away. D’Urville commanded voyages of exploration to the South Pacific (1826–29) and the Antarctic (1837–40), resulting in extensive revisions of existing charts and discovery or redesignation of island groups. As a botanist and cartographer he left his mark, giving his name to several seaweeds, plants and shrubs, and places such as D’Urville Island.

Jules Dumont d’Urville – Early Years

Dumont was born in 1790 at Condé-sur-Noireau in Lower Normandy. After the death of his father when he was six, his mother’s brother, the Abbot of Croisilles, took charge of his education and taught him Latin, Greek, rhetoric and philosophy. From 1804 Dumont studied at the lycée Impérial in Caen and began to read the encyclopédists and the reports of travel of Bougainville, Cook and Anson, and he became so deeply passionate about that he enlisted in the navy.[6] But, being a cadet at the time of the Napoleonic wars meant to stay in the port, since French ships were blockaded in their ports by the absolute domination of the British Royal Navy. Finally in 1814, when Napoleon had been exiled to Elba, Dumont undertook his first short navigation of the Mediterranean Sea.

The Venus de Milo

In 1819, Dumont d’Urville sailed on board the Chevrette, under the command of Captain Gauttier-Duparc, to carry out a hydrographic survey of the islands of the Greek archipelago. There, d’Urville helped the French government gain possession of what became one of the best-known Greek sculptures, the Venus de Milo, which had been unearthed on the Aegean island of Mílos in that year.[1] This earned Dumont the title of Chevalier (knight) of the Légion d’honneur, the attention of the French Academy of Sciences and promotion to lieutenant.

Around the World

In 1822 he served on a voyage around the world on board of La Coquille, which sailed from Toulon with the objective of collecting as much scientific and strategic information as possible on the area to which it was dispatched. During this voyage, Dumont discovered the Adélie penguin, which is named after his wife. The expedition returned to France in 1825 and brought back an imposing collection of animals and plants collected on the Falkland Islands, on the coasts of Chile and Peru, in the archipelagos of the Pacific and New Zealand, New Guinea and Australia.

South Pacific

Dumont d’Urville’s next mission took him to the South Pacific, where he searched for traces of explorer Jean-François La Pérouse [2], lost in that region in 1788. The ship La Coquille was renamed the Astrolabe in honour of one of the ships of La Pérouse. On this voyage he charted parts of New Zealand and visited the Fiji and Loyalty islands, New Caledonia, New Guinea, Amboyna, Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), the Caroline Islands, and the Celebes. In February 1828 d’Urville sighted wreckage, believed to be from the frigates of La Pérouse, at Vanikoro in the Santa Cruz Islands. The expedition returned to France in 1829. The voyage resulted in extensive revision in charts of South Sea waters and redesignation of island groups into Melanesia, Micronesia, Polynesia, and Malaysia. D’Urville also returned with about 1,600 plant specimens, 900 rock samples, and information on the languages of the islands he had visited. Promoted to capitaine de vaisseau (captain) in 1829, he conveyed the exiled king Charles X to England in August 1830.[1]

The Travel Report

Dumont d’Urville now was put in charge of writing the report of his travels. The five volumes were published at the expense of the French government between 1832 and 1834. During these years d’Urville, who was already a poor diplomat, became more irascible and rancorous as a result of his gout, and lost the sympathy of the naval leadership. In his report, he criticised harshly the military structures, his colleagues, the French Academy of Sciences and even the King – none of which, in his opinion, had given the voyage of the Astrolabe due acknowledgment.

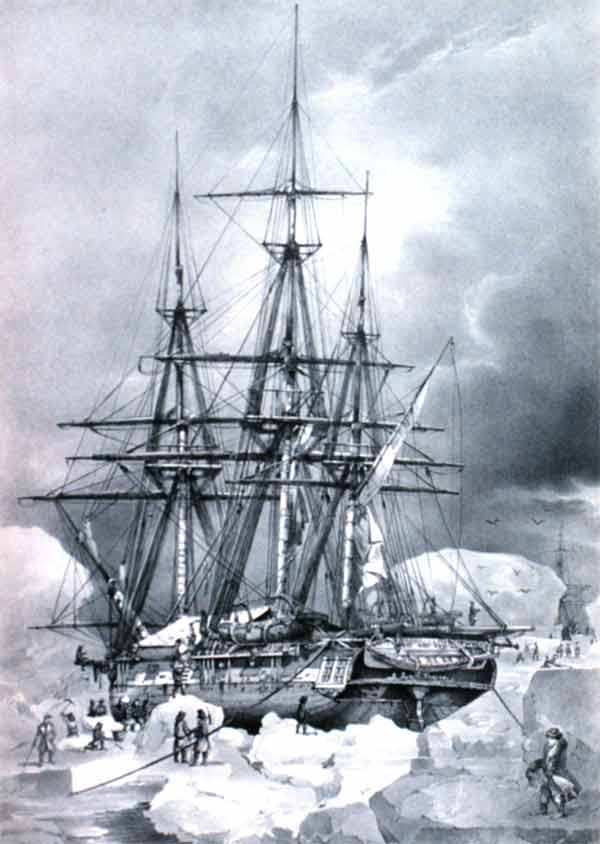

L’Astrolabe making water on a floe 6 February 1838

Antarctica

D’Urville was accused of arrogance and self-seeking, of treating his crew harshly and a willingness to exaggerate his findings. Whether true or not, he nevertheless was desk-bound, without a command, for the next seven years.[4] In 1837 d’Urville set sail again with two ships, the Astrolabe and Zélée, from Toulon on a voyage to Antarctica. King Louis-Philippe had ordered that the expedition must aim for the South Magnetic Pole to claim it for France. Dumont d’Urville hoped to sail beyond the 74°15′ S reached by James Weddell in 1823.[3] After surveying in the Straits of Magellan, d’Urville’s ships reached the pack ice at 63°29′ S, 44°47′ W, but they were ill-equipped for ice navigation. Unable to penetrate the pack, they coasted it for 300 miles to the east. Heading westward, they visited the South Orkneys and the South Shetlands and discovered Joinville Island and Louis Philippe Land before scurvy forced them to stop at Talcahuano, Chile. After proceeding across the Pacific to the Fiji and Pelew (now Palau) islands, New Guinea, and Borneo, they returned to the Antarctic, hoping to discover the magnetic pole in the unexplored sector between 120° and 160° E. In January 1840 they sighted the Adélie coast, south of Australia, and named it for Mme d’Urville. The expedition reached France late in 1841.

Later Years

On his return Dumont d’Urville was promoted to Rear Admiral and was awarded the Gold Medal of the Société de Géographie (Geographical Society of Paris), later becoming its president. The French government was so delighted with their accomplishments that they shared 15,000 gold francs among the 130 survivors of the expedition.[4] D’Urville then took over the writing of the report of the expedition, Voyage au pôle Sud et dans l’Océanie sur les corvettes l’Astrolabe et la Zélée 1837-1840, which were published between 1841 and 1854 in 24 volumes, plus seven more volumes with illustrations and maps. The following year d’Urville was killed, with his wife and son, in the very first French railway disaster, generally known as the Versailles train crash.

Nicoletta Brown, Lecture 14A: The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Part 1, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville, French explorer, at Britannica Online

- [2] Jean-François de La Pérouse and his Voyage around the World, SciHi blog, August 1, 2013.

- [3] James Weddell and the Southern Ocean, SciHi blog, August 1, 2015.

- [4] Jules-Sébastien-César Dumont d’Urville, at South-Pole.com

- [5] Story: Dumont d’Urville, Jules Sébastien César, The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

- [6] Louis Antoine de Bougainville and his Voyage Around the World, SciHi Blog

- [7] Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville at Wikidata

- [8] Dumont (1833) Voyage de la corvette L’Astrolabe…Atlas – digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library.

- [9] Dunmore, John (2007). The Life of Dumont d’Urville: From Venus to Antarctica. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing

- [10] Nicoletta Brown, Lecture 14A: The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, Part 1, Nicoletta Christina @ youtube

- [11] Timeline of French explorers, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol: #40 | Whewell's Ghost