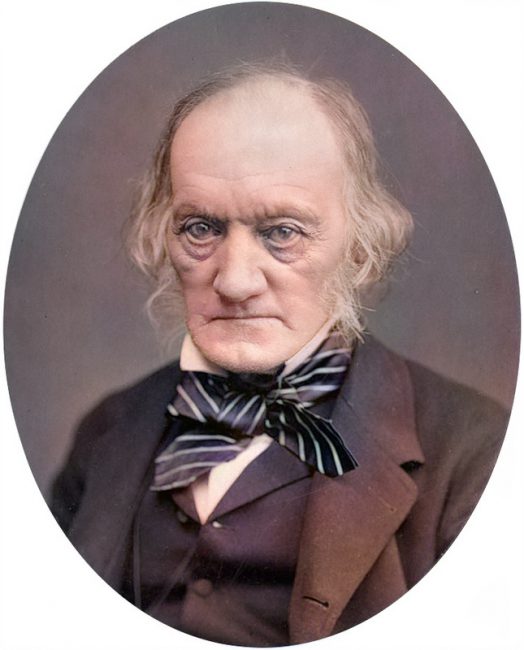

Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892)

On July 20, 1804, English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist Sir Richard Owen was born. Despite being a controversial figure, Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils. Owen is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria (meaning “Terrible Reptile” or “Fearfully Great Reptile“). And today, dinosaurs seem to be more popular than ever, taking into account recent revenues of the latest sequel of the Jurrasic Park series, which have surpassed 1.5B US$ this weekend [1]. But, Owen is also remembered for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin‘s theory of evolution by natural selection, which created much bitterness towards Owen and alienated a younger generation of naturalists.

“Manifold subsequent experience has led to a truer appreciation and a more moderate estimate of the importance of the dependence of one living being upon another.”

– Sir Richard Owen, as stated in “The Edinburgh Review” (1860)

Richard Owen – Early Years

Richard Owen was born in Lancaster as one of six children of a West Indian Merchant. In 1820, he was apprenticed to a local surgeon and apothecary and, in 1824, he proceeded as a medical student to the University of Edinburgh. He left the university in the following year and completed his medical course in St Bartholomew‘s Hospital, London, where he came under the influence of the eminent surgeon John Abernethy, who was also President of the Royal College of Surgeons. He was induced by Abernethy to accept the position of assistant to William Clift, conservator of the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons as curator of the Hunterian Collections. This congenial occupation soon led him to abandon his intention of medical practice and his life thenceforth was devoted to purely scientific labors.

The Remains of Extinct Animals

Owen assisted in cataloging the Hunterian Collection of thirteen thousand human and animal anatomical specimens, which had been purchased by the Crown after the death of its owner, the famous surgeon John Hunter. The Crown had passed the Hunterian Collection to the Royal College, with the stipulation that the collection be made available to the public and medical community by the founding of a lecture series and a museum. Unfortunately, a previous caretaker of Hunter‘s estate had burned most of Hunter‘s papers and documentation, which meant that Owen had to identify and catalogue the entire collection anew. But by 1830 he had labelled and identified every specimen, reorganized the entire collection and was publishing a catalogue.[3] Moreover, he had acquired the unrivaled knowledge of comparative anatomy that enabled him to enrich all departments of the science and especially facilitated his researches on the remains of extinct animals. In the same year, Owen became the youngest member of the Zoological Society of London.

The Paris’ Debates

His Memoir on the Pearly Nautilus (1832) was a classic, and he became a highly respected anatomist. After meeting famous French naturalist and zoologist George Cuvier [5] in 1830 and attending the 1831 seminal Paris‘ debates between Cuvier and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire about the possibility of biological evolution,[5,7] Owen was appointed Hunterian professor of Comparative Anatomy and Physiology in the Royal College of Surgeons in 1836 and, in 1849, he succeeded William Clift as conservator. He held the latter office until 1856, when he became superintendent of the natural history department of the British Museum. On retirement in 1883, he was made a knight of the Order of the Bath.

The Giant Moa

It was in 1837, when Owen gave his first series of rather popular Hunterian Lectures to the public that were attended by royalty and many important figures in Victorian England, including Charles Darwin,[6] back from his expeditions on the H.M.S. Beagle. At the same time, Owen was working on describing the fossil vertebrates which Darwin had brought back from South America on the Beagle.[3] One of Owen‘s most dramatic achievements was his scientific prediction based on the study of a tiny fragment of fossilized bone. From observation alone, Owen concluded it belonged to a large extinct bird that once lived in New Zealand. He was proved correct when more fossils were discovered, confirming the bone belonged to the largest bird that ever lived, the giant moa.[4]

Richard Owen with the Giant Moa Skeleton (1879)

Accusations

His career was tainted by accusations that he failed to give credit to the work of others and even tried to appropriate it in his own name. This came to a head in 1846, when he was awarded the Royal Medal for a paper he had written on belemnites. Owen had failed to acknowledge that the belemnite had been discovered by Chaning Pearce, an amateur biologist, four years earlier. As a result of the ensuing scandal, he was voted off the councils of the Zoological Society and the Royal Society. Unfortunately, Owen was not easy to get along with; his vain, arrogant, envious, and vindictive personality seems to have inspired distaste in most of his colleagues. Charles Darwin reminisced in his autobiography that Owen became his enemy after the publication of the Origin of Species, “not owing to any quarrel between us, but as far as I could judge out of jealousy at its success.”[3] Owen is also said to have coached Bishop Wilberforce in his debate against Thomas Huxley, one of Darwin’s chief defenders.[7]

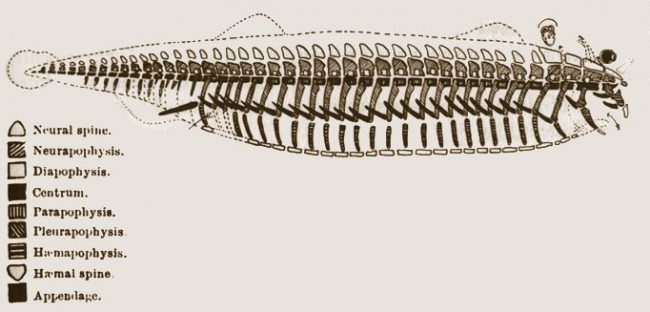

Owen, R. (1847). On the archetype and homologies of the vertebrate skeleton. London.

…and more Errors

Another notorious error by Owen involved Archaeopteryx, the first known fossil bird, an object Owen had obtained for the museum and had described for publication in 1863. It fulfilled Darwin‘s prediction that a proto-bird with unfused wing fingers would be found, although Owen described it unequivocally as a bird. The fossil was reexamined in 1954, and scientists determined that Owen had got it upside down, dorsal for ventral, and had missed its two most important features: the breastbone, which was flat, proof that the bird could not fly but glided; and the natural cast of the brain case, which was like that of a reptile.[2]

Later Years

After retiring in 1883 Owen was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) on 5 January 1884, becoming “Sir”. Already in 1873 he had been honoured as Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB). In 1888 Owen was awarded the Linné Medal of the Linnean Society of London together with Joseph Dalton Hooker. In 1852 he was honoured in Germany with the Pour le mérite for sciences and arts at the suggestion of Alexander von Humboldt. The Australian Royal Society of New South Wales honoured him in 1878 with the first award of the Clarke Medal. The suicide of his only son in 1886 embittered him. He was deaf and suffering from stomatitis[22] Owen died on 18 December 1892.

Paul Sereno: What can fossils teach us?, [13]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Jurrasic World at Box Office Mojo, on July 19, 2015.

- [2] Sir Richard Owen – British anatomist and paleontologist at Britannica Online

- [3] Richard Owen at UCMP Berkeley

- [4] Richard Owen at the Natural History Museum

- [5] George Cuvier and the Fossils, SciHi Blog

- [6] Charles Darwin’s ‘On the Origin of Species’, SciHi blog

- [7] The Great Paris Academic Dispute of 1830, SciHi Blog

- [8] Works written by or about Richard Owen at Wikisource

- [9] Works by or about Richard Owen at Internet Archive

- [10] Owen, Richard (1852). “Description of the impressions and footprints of the Protichnites from the Potsdam sandstone of Canada”. Geological Society of London Quarterly Journal. 8 (1–2): 214–225.

- [11] Owen, Richard (published anonymously) (April 1860). “Darwin on the Origin of Species“. Edinburgh Review. 111: 487–532.

- [12] Sir Richard Owen at Wikidata

- [13] Paul Sereno: What can fossils teach us?, TED @ youtube

- [14] Timeline for Sir Richard Owen via Wikidata