Cicero Denounces Catiline, fresco by Cesare Maccari, 1882–88

On October 21, 63 BC, Roman philosopher, politician, and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero presented evidence to the members of the Roman senate as proof that Lucius Sergius Catilina was preparing a conspiracy to overthrow the Roman Republic, and in particular the power of the aristocratic Senate. Actually, the Catilinarian Conspiracy is one of the best-documented episodes of ancient history. It was the attempted seizure of power at Rome by the disaffected aristocrat Catiline. Marcus Tullius Cicero,[8] acting Roman consul during this time was able to suppress the conspiracy, but caused vehement controversies, because he had executed the ringleaders. Cicero’s speeches to the senate and people during the crisis have become rather popular. In fact, attending Latin courses in high school, we did translate large parts of his famous first speech to the Roman senate, of which the opening remarks are still widely remembered and used after 2,000 years:

“Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra? Quam diu etiam furor iste tuus nos eludet? Quem ad finem sese effrenata iactabit audacia?”

(How long, O Catiline, will you abuse our patience? And for how long will that madness of yours mock us? To what end will your unbridled audacity hurl itself?)

Who wasLucius Sergius Catilina?

Lucius Sergius Catilina, in English known as Catiline, was born in 108 BC to one of the oldest patrician families in Rome, the gens Sergia. Although his family was of consular heritage, they were then declining in both social and financial fortunes, which should dramatically shape Catiline’s ambitions and goals as he would desire above all else to restore the political heritage of his family along with its financial power.

“He had a powerful intellect and great physical strength, but a vicious a depraved.”

(Sallust, The Conspiracy of Catiline)

A Man of Questionable Character

According to the existing sources and references, Catilina must have been a man of questionable character. An able commander, he had a distinguished military career. During the Roman Civil War in the times of the late Roman Republic he supported Lucius Cornelius Sulla. During Sulla’s proscriptions he allegedly tortured, maimed and then killed and beheaded his brother-in-law, Marcus Marius Gratidianus. Then, carrying this man’s severed head through the streets of Rome and having Sulla add him to the proscription later to make the murder legal. Furthermore, he is also accused of murdering his first wife and son so that he could marry the wealthy and beautiful Aurelia Orestilla, daughter of the Consul of 71 BC, Gnaeus Aufidius Orestes. In 73 BC, he was brought to trial for adultery with the Vestal Virgin, Fabia, who was a half-sister of Cicero’s wife, Terentia, but Quintus Lutatius Catulus, the principal leader of the Optimates, testified in his favor, and eventually Catiline was acquitted.

Trying to seize the Power

After an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the government already in 65 BC, when Catiline and his fellow conspirators tried to assassinate the Consuls, a second plot was devised by Catiline with the help of a group of aristocrats and disaffected veterans, to overthrow the Roman Republic in 63 BC. Catiline, who was running for the consulship a second time after having lost the first time around, tried to ensure his victory by resorting to outlandish, blatant bribery. Cicero as one of the two elected current consuls in indignation, issued a law prohibiting machinations of this kind. It was obvious to all that the law was directed specifically at Catiline. Catilina also was heavily indebted after the lost consular elections.

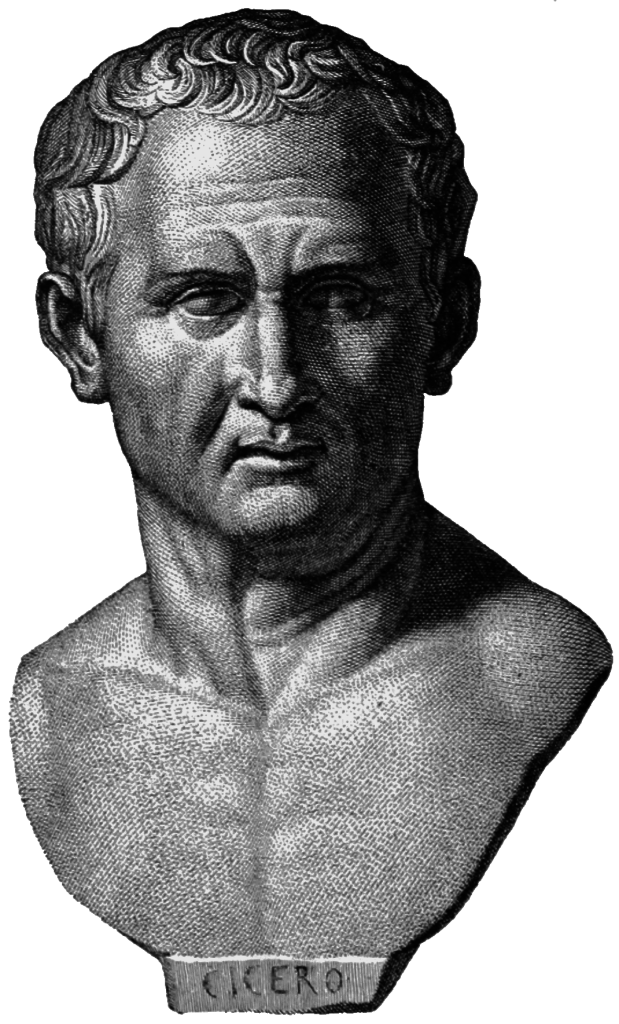

Cicero, engraving after antique inscribed portrait in Apsley House, London

The Catiline Orations

Catiline, in turn, conspired with some of his minions to murder Cicero and the key men of the Senate on the day of the election. Cicero discovered the plan and postponed the election to give the Senate time to discuss the attempted coup d’état. Cicero procured a Senatus Consultum Ultimum (a declaration of martial law) and drove Catiline from the city with four vehement speeches – later referred to as the Catiline Orations -, which to this day remain outstanding examples of his rhetorical style. There, he listed Catiline’s and his followers’ debaucheries, and denounced Catiline’s senatorial sympathizers as roguish and dissolute debtors clinging to Catiline as a final and desperate hope. Cicero demanded that Catiline and his followers leave the city. Incensed at these accusations, Catiline exhorted the Senate to recall the history of his family and how it had served the republic, instructing them not to believe false rumors and to trust the name of his family. He finally accused them of placing their faith in a “homo novus“, Cicero, over a “nobilis”, himself. Immediately afterward, Catiline rushed home and the same night ostensibly complied with Cicero’s demand and fled Rome.

“O tempora o mores! ”

(Oh the times, oh the customs!) (Cicero in his first speech against Catilina, deploring the viciousness and corruption of his age.)

Public Enemies

Next day, Cicero awoke the terror of the Roman people by a second oration delivered in the forum, in consequence of which Catiline and Manlius were declared public enemies, and the consular colleague Antonius Hybrida was despatched with an army against them. Meanwhile the imprudence of the conspirators in Rome brought about their own destruction. Some deputies from the Gaulish tribe of the Allobroges, who had been sent to Rome to obtain redress for certain grievances, were approached by P. Lentulus Sura, the chief of the conspirators, who endeavored to induce them to join him. After considerable hesitation, the deputies decided to turn informants.

Betraying the Plot

The plot was betrayed to Cicero, at whose instigation documentary evidence was obtained, implicating Lentulus and others. They were arrested, proved guilty, and on the 5th of December condemned to death and strangled in the underground dungeon on the slope of the Capitol. After the executions, Cicero announced to a crowd gathering in the Forum what had occurred. Thus, an end was made to the conspiracy in Rome. This act, which was opposed by Julius Caesar and advocated by Cato Titicensis,[7] was afterwards vigorously attacked as a violation of the constitution, on the ground that the senate had no power of life and death over a Roman citizen. Due to the development in Rome, Catilina lost more and more followers in the city. He therefore tried to retreat with his army to Gaul in order to continue to act from there. In 62 B.C. Catiline finally died in the Battle of Pistoria, when he threw himself into the turmoil of battle in the face of defeat. The historian Sallust describes the death of the Catiline in a final battle further pursuing the course of his futile conspiracy engaging the army of Antonius Hybrida near Pistoria:

“But Catiline was found far in advance of his men amid a heap of slain foemen, still breathing slightly, and showing in his face the indomitable spirit which had animated him when alive.”

(Sallust, The Conspiracy of Catiline)

Aftermath

The person of Lucius Sergius Catilina became a proverbial symbol of villainy in Roman times after the suppression of the Catilinar conspiracy. His name was also used as a dirty name for unloved Roman emperors. Vergil also lets him appear in his Aeneid, written about 50 years after the suppression of the conspiracy, where the furies torture him in the underworld. For Roman historians who dealt with civil disobedience and insurrection in the course of Roman history, the Catilina case was the prime example they used, even though it represented a reversal of the chronological order.

Mary Ann Glandon, Politics as Vocation in Cicero and Burke, [10]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Marcus Tullius Cicero: Oratio in Catilinam Prima in Senatu Habita (in Latin)

- [2] Marcus Tullius Cicero: The First Oration Against Catiline (in English Translation)

- [3] Marcus Tullius Cicero: Erste Rede gegen Catilina (in German Translation)

- [4] Chronology of Catiline’s Conspiracy

- [5] An alternative primary source for the Catilinarian Conspiracy is Gaius Sallustius Crispus: The Catilinarian Conspiracy

- [6] Catiline at Wikidata

- [7] Veni, Vidi, Vici – According to Iulius Caesar, SciHi Blog

- [8] Marcus Tullius Cicero – a Homo Novus, SciHi Blog

- [9] “Chronology of Catiline’s Conspiracy”. The Latin Library

- [10] Mary Ann Glandon, Politics as Vocation in Cicero and Burke, 2013, Lumen Christi Institute @ youtube

- [11] Fuhrmann, Manfred (1992). Cicero and the Roman Republic. Oxford: Blackwell.

- [12] Sallust (1921) [1st century BC]. “Bellum Catilinae”. Sallust. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by Rolfe, John C. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

- [13] Cicero (1856). “Against Catiline”. Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero. Vol. 2. Translated by Yonge, Charles Duke. London: Henry G. Bohn

- [14] Timeline of conspiracies, according to DBpedia and Wikidata