The Venerable Bede (672/73 – 735) writing the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, from a 12th century codex at Engelberg Abbey in Switzerland.

On May 26, 735 CE, Anglo-Saxon Benedictine, theologian and historian Bede, also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable, passed away. He is famous as a scholar and author of numerous works, of which the best known is the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), which gained him the title “The Father of English History”.

Bede the Venerable – Early Life

“It is reported that there was then such perfect peace in Britain, wheresoever the dominion of King Edwin extended, that, as is still proverbially said, a woman with her newborn babe might walk throughout the island, from sea to sea, without receiving any harm.”

– Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), Book II, chapter 16

Bede was born in 672 or 673 near Wearmouth in Northumbria, in what is now Sunderland in northern England. Already at the age of seven he came to the monastery of St. Peter in Wearmouth, in the care of the teachers and educators Benedict Biscop and Ceolfrid. When Biscop founded the monastery of St. Paul at Jarrow near Newcastle upon Tyne in 682, young Bede moved there with Abbot Ceolfrid. He became a deacon at the age of 19 and a priest at 30. He worked as a teacher and spent the rest of his life in the monastery of Jarrow.

Writings

Bede the Venerable is considered one of the most important scholars of the early Middle Ages. His writings are attributed to the Northumbrian Renaissance. He covered with his writings almost all fields of knowledge of the time and in many cases wrote works that achieved canonical validity for a long time. The field of grammar includes writings on orthography and metrics, as well as the encyclopedia De natura rerum, which also imparts a great deal of scientific knowledge, and the field of rhetoric includes a work on rhetorical figures (De schematibus et tropis), into that of astronomy and arithmetic several works on the calculation of time, the so-called computistics, among them De temporum ratione, which also contains a world chronicle in its second part, the Easter tables (Circulus paschalis), the calendar, a work on the division of time (De temporibus) and other smaller works, some of which are disputed in their authenticity.

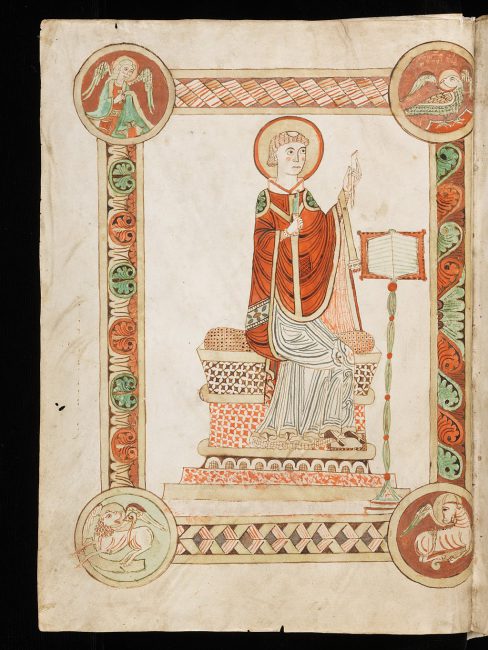

![A page from a copy of Bede's Lives of St. Cuthbert, showing King Athelstan presenting the work to the saint. This manuscript was given to St. Cuthbert's shrine in 934.[100]](http://scihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Athelstan-461x650.jpeg?_t=1654343590)

A page from a copy of Bede’s Lives of St. Cuthbert, showing King Athelstan presenting the work to the saint. This manuscript was given to St. Cuthbert’s shrine in 934.

Fixing time – from movable Feasts to Calendar Errors

The main interest of that time was the calculation of the movable feast of Easter, which, if possible, should be binding for all countries and dated at the same time. This was of some explosiveness for Bede in that in his habitat the Alexandrian-Roman Easter cycle and the practice of calculating the date of Easter practiced in Ireland and England clashed and led to conflicts over the calculation of the date of Easter; moreover, it was necessary to distinguish himself from the Easter cycle of Victorius of Aquitaine, which was common in the Merovingian Frankish Empire. A de facto agreement had been reached at the Synod of Whitby in 664, but clear and long-term implementation was still lacking. Bede created a coherent system of recording and calculating time, enforced the reckoning of time in years after Christ’s birth, which is still authoritative today, and continued the Easter tables of Dionysius Exiguus until the year 1063. Bede’s Easter table owes its sophisticated Metonic structure to the mental efforts of his computist predecessors Anatolius (c. AD 260), Theophilus (c. AD 390), Annianus (c. AD 412), Cyril (c. AD 425), and Dionysius Exiguus (c. AD 525). He also demonstrated a calendar error that was not corrected until the Gregorian calendar reform in the 16th century [1], and calculated (not only from biblical specifications) March 18, 3952 B.C. as the beginning of the world.

Ecclesiastical History of the English People

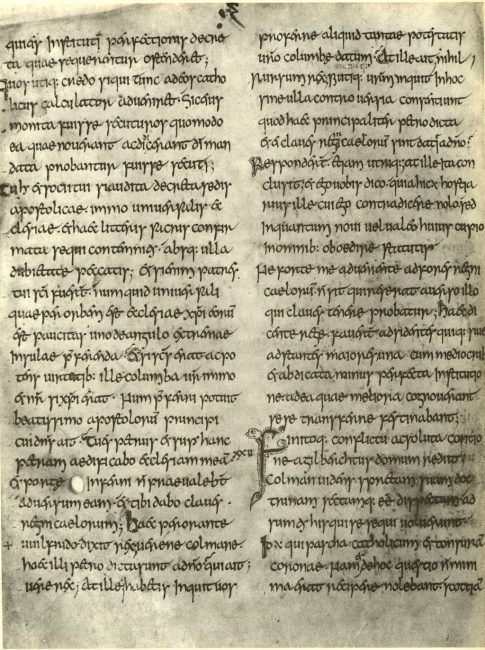

In his historical accounts, he shows himself influenced by Dionysius Exiguus as far as dating practices are concerned. His Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (“Ecclesiastical History of the English People“) of 731 is one of the most important historiographical works of the Occident and impresses with a neutral evaluation of sources. The work covers the history of England from the conquest by Gaius Iulius Caesar to the year 731 [2], dealing among other things with the Anglo-Saxon mainland mission to the Frisians and Old Saxons. Alfred the Great later translated this church history into Old English.

Bede, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum in a late 8th century manuscript. London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius C II, fol. 87v

Further Writings

Other historiographical works are today more likely to be classified as hagiography, although no such distinction existed in the early Middle Ages. For history was salvation history, as expressed in the Vita (et miracula) Cuthberti in verse and in a prose version, in the Martyrologium Bedae, and in a collected biography of the abbots of Wearmouth. The widest space is occupied by numerous commentaries on various biblical books, which fall into the field of theology, more specifically exegesis. An aid to exegesis is the writing on biblical-ecclesiastical geography (De locis sanctis). Homilies (Homiliae) complete the theological work. Only fragments of Bede’s poems have survived, including hymns, epigrams, a poem on the Last Judgment (De die iudicii) as well as psalms. Old English works such as the “Song of the Dead” are also said to have been written by the scholar. A small number of letters have also survived.

Canonization

“The quality which makes his work great is not his scholarship, nor the faculty of narrative which he shared with many contemporaries, but his astonishing power of co-ordinating the fragments of information which came to him through tradition, the relation of friends, or documentary evidence. In an age when little was attempted beyond the registration of fact, he had reached the conception of history. It is in virtue of this conception that the Historia Ecclesiastica still lives after twelve hundred years.”

– Sir Frank Stenton Anglo-Saxon England (1971), p. 187

The veneration of Bede was especially great in the early Middle Ages. He enjoyed almost church father-like status, since he relied on the orthodox authorities. This was especially true of his impact as a “researcher of the Holy Scriptures,” as a computist, and as a teacher, which is also reflected in numerous false attributions. His writings also spread to the continent. In 1899, Pope Leo XIII canonized Bede and named him Doctor ecclesiae. Bede’s remains rest in the Galilean Chapel of Durham Cathedral.

How he received his Nickname

Bede is usually called “venerable” (venerabilis) and not “holy”. The Legenda aurea provides two explanations for this. The first is: The old monk, blinded, was walking one day with his guide through a lonely stony valley. Now, as a joke, the guide claimed that the valley was full of silent people who wanted to hear the monk. Bede began to preach, and when he spoke at the end, “Forever,” the stones replied, “Amen, venerable Father,” or, in a slightly different version, the angels from heaven, “You have spoken well, venerable Father.” According to the other explanation, a cleric wanted to write Bede’s epitaph, but could not complete the Latin hexameter. One word did not fit into the verse measure:

“Hac sunt in fossa Bedae sancti ossa.” (“In this tomb are the bones of St. Beda.”)

When he had spent a whole night fruitlessly thinking about it, the cleric found the inscription finished chiseled in the morning, apparently by an angel’s hand:

“Hac sunt in fossa Bedae venerabilis ossa.” (“In this tomb are the bones of the venerable Beda.”)

Jim Carter meets the Venerable Bede, [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Days That Never Happened – The Gregorian Calendar, SciHi Blog

- [2] Veni, Vidi, Vici – according to Julius Caesar, SciHi Blog

- [3] Works by or about Bede at Internet Archive

- [4] Bede’s World: the museum of early medieval Northumbria at Jarrow

- [5] Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Books 1–5, L.C. Jane’s 1903 Temple Classics translation

- [6] Saint Bede, complete works, in Latin, with historical works also in English at The Online Library of Liberty

- [7] Karl Werner: Beda der Ehrwürdige und seine Zeit. 2. Auflage. Wien 1881

- [8] Bede at Wikidata

- [9] Jim Carter meets the Venerable Bede, The British Library @ youtube

- [10] Timeline of Chronologists, via Wikidata and DBpedia