You have read the title? I guess, you might be scared now, but Pierre Gassendi was a decent fellow… On January 22, 1592, French philosopher, priest, scientist, astronomer, and mathematician. Pierre Gassendi was born. Gassendi revived Epicureanism as a substitute for Aristotelianism, attempting in the process to reconcile Atomism‘s mechanistic explanation of nature with Christian belief in immortality, free will, an infinite God, and creation.He clashed with his contemporary Descartes on the possibility of certain knowledge. He was also an active observational scientist, publishing the first data on the transit of Mercury in 1631.

“Man lives very well upon flesh, you say, but, if he thinks this food to be natural to him, why does he not use it as it is, as furnished to him by Nature? But, in fact, he shrinks in horror from seizing and rending living or even raw flesh with his teeth, and lights a fire to change its natural and proper condition. … What is clearer than that man is not furnished for hunting, much less for eating, other animals?”

– Pierre Gassendi, Letter to Van Helmont, [13]

Pierre Gassendi – Early Years

Pierre Gassendi was born at Champtercier, near Digne, in France to Antoine Gassend and Françoise Fabry, a family of commoners. Already at a very early age he showed academic potential and attended the college at Digne, where he displayed a particular aptitude for languages and mathematics. At age 16, he entered the University of Aix-en-Provence, to study philosophy. In 1612 the college of Digne called him to lecture on theology. Four years later he received the degree of Doctor of Theology at Avignon, and in 1617 he took holy orders. In the same year he answered a call to the chair of philosophy at Aix-en-Provence University, and seems gradually to have withdrawn from theology.

Paradoxical Exercises on Aristotle

Pierre Gassendi‘s career as a priest is a crucial facet of his intellectual constitution: his writings reflect an unbending allegiance to Holy Scripture and Church teachings, though not necessarily in orthodox doctrinal lights. He was ordained at the age of 24 or 25 and, while there is no question of the strength of his faith, one motivation for his career in the Church appears to be its provision of a sinecure. [1] He lectured principally on the Aristotelian philosophy, conforming as far as possible to the traditional methods while he also followed with interest the discoveries of Galileo and Kepler.[3,5] He came into contact with the astronomer Joseph Gaultier de la Vallette (1564–1647). In 1623 the Society of Jesus took over the University of Aix. They filled all positions with Jesuits, who disapproved of Gassendi’s anti-Aristotelianism, and compelled him to leave. He left, returning to Digne, and then travelled for the chapter to Grenoble. In 1624 he printed the first part of his Exercitationes paradoxicae adversus Aristoteleos (Paradoxical Exercises Against the Aristotelians).

Philosophical Studies

Pierre Gassendi thereafter engaged in many scientific studies with his patron, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc,[6] until the latter’s death in 1637, which seemed to afflict him deeply. Gassendi travelled in Flanders and in Holland, and returned to France in 1631, and two years later became provost of Digne Cathedral. During this time he wrote some works, at the insistence of theologian and mathematician Marin Mersenne. They included his examination of the mystical philosophy of Robert Fludd, an essay on parhelia, and some observations on the transit of Mercury. In 1641, he met Thomas Hobbes in Paris,[7] where Gassendi also gave some informal philosophy classes, which according to the biographer Grimarest included Molière and Cyrano de Bergerac .

Metaphysical Knowledge of the Essence of Things is Impossible

In 1642 Mersenne engaged Gassendi and other eminent thinkers in controversy with René Descartes to contribute a commentary on the manuscript of René Descartes’s Meditations.[4] This led to Gassendi’s objections to the fundamental propositions of Descartes published as the Fifth Set of Objections in the works of Descartes. In 1645 Gassendi was appointed professor of mathematics at the Collège Royal in Paris, and lectured for several years with great success. However, his poor health meant that he could only teach for a short time. In addition to controversial writings on physical questions, there appeared during this period the first of the works for which historians of philosophy remember him. Gassendi attempted to find what he called a middle way between skepticism and dogmatism. He argued that, while metaphysical knowledge of the “essences” (inner natures) of things is impossible, by relying on induction and the information provided by “appearances” one can acquire probable knowledge of the natural world that is sufficient to explain and predict experience.

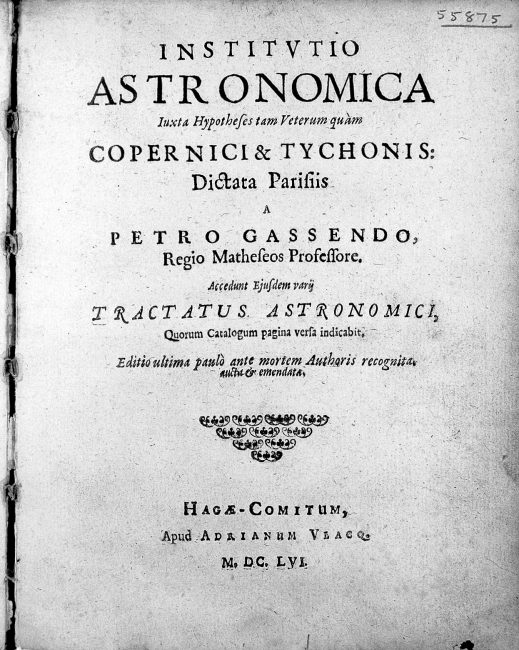

Title page of Pierre Gassendi, “Institvtio astronomica iuxta hypotheses tam veterum quàm Copernici et Tychonis … Accedunt … tractatus astronomici“, 1656

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0

Scientist Biographies

Gassendi published the first complete biography of a scientist ever, the first and only biography of Tycho Brahe, which came about through direct contact with contemporary witnesses still alive at the time.[11] Other biographies of Gassendi included Epicurus, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, Georg von Peuerbach, Regiomontanus and Nicolaus Copernicus. He also gave an overview of the followers and opponents of Copernicus’ teachings until about 1615.

Mechanistic Atomism in Accordance with Roman Catholicism

The best theory of such a world, in Gassendi’s opinion, is the ancient atomism according to Epicurus. There, atoms are eternal, differently shaped, and moving at different speeds. Gassendi argued that such atoms must have some of the physical features of the visible objects they constitute, such as extension, size, shape, weight, and solidity. The atoms collide and agglomerate, resulting in events in the perceptible world.[2] In 1647 he published the well-received treatise De vita, moribus, et doctrina Epicuri libri octo followed by further publications on Diogenes Laërtius and another commentary on Epicurus. Gassendi believed that there was no conflict between his mechanistic atomism and the doctrines of Roman Catholicism; indeed, he took pains to emphasize their compatibility.

Final Years

In 1648 ill-health compelled him to give up his lectures at the Collège Royal. He travelled in the south of France and spent nearly two years at Toulon, where the climate suited him. In 1653 he returned to Paris and resumed his literary work publishing lives of Copernicus and of Tycho Brahe. On October 24, 1655, after a long illness, Gassendi died at the age of 63 in the house of a patron, the nobleman Habert de Montmor. at Paris from a lung disease.

Lawrence Principe, Scientism and the Religion of Science, [14]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Pierre Gassendi entry by Saul Fisher in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- [2] Pierre Gassendi at Encyclopedia Britannica

- [3] The Galileo Affair, SciHi Blog, February, 13, 2014.

- [4] Cogito ergo sum – Réne Descartes, SciHi Blog, March 31, 2013.

- [5] And Kepler Has His Own Opera – Kepler’s 3rd Planetary Law, SciHi Blog, May 15, 2012.

- [6] Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc and the Discovery of the Orion Nebula, SciHi Blog

- [7] Man is Man’s Wolf – Thomas Hobbes and his Leviathan, SciHi Blog

- [8] Works written by or about Pierre Gassendi at Wikisource

- [9] Fisher, Saul. “Pierre Gassendi”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- [10] Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Gassendi, Pierre“. Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 503–504.

- [11] Tycho Brahe – The Man with the Golden Nose, SciHi Blog

- [12] Howard Williams, The Ethics of Diet: A Catena of Authorities Deprecatory of the Practice of Flesh-eating (London: F. Pitman, 1883), pp. 103-104.

- [13] Pierre Gassendi at Wikidata

- [14] Lawrence Principe, Scientism and the Religion of Science, The Wheatley Institution, 2013, Bloomsbury Publishing @ youtube

- [15] Timeline for Pierre Gassendi, via Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #32 | Whewell's Ghost