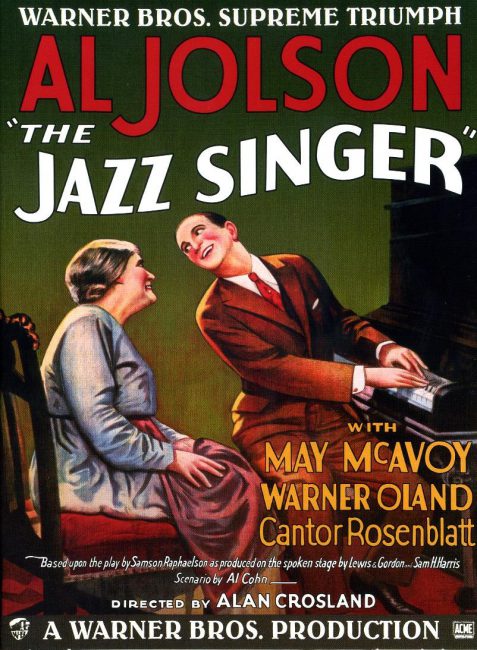

Poster for the movie The Jazz Singer (1927), featuring stars Eugenie Besserer and Al Jolson. Warner Bros.

On October 6, 1927, the first feature-length motion picture with synchronized dialogue sequences, The Jazz Singer premiered. With its Vitaphone sound-on-disc system it heralded the commercial ascendance of the “talkies” and the decline of the silent film era.

The Advent of the Talkies

We all know that it started with the silent films already at the end of the 19th century as a simple and innocent fairground attraction. In silent films for entertainment the dialogue is transmitted through muted gestures, mime and title cards. But, the idea of combining motion pictures with recorded sound is nearly as old as film itself. Actually, the first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, showing short films of theater, opera, and ballet excerpts to be presented at the Paris Exposition in 1900. But because of the technical challenges involved, synchronized dialogue was only made practical in the late 1920s.

Synchronization and Fidelity

Three major problems persisted, leading to motion pictures and sound recording largely taking separate paths for a generation. The most important issue of all was synchronization: pictures and sound were recorded and played back by separate devices, which were difficult to start and maintain in almost perfect synchronicity. In a synchronized dialogue scene, you will already notice, when both sound and movement of the speaker’s lips are out of synchronization if they are out of tune for only 80 miliseconds. Another problem was sufficient playback volume, which was also hard to achieve. While motion picture projectors soon allowed film to be shown to large theater audiences, audio technology before the development of electric amplification could not project to satisfactorily fill large spaces. Third, there was the challenge of recording fidelity. The primitive systems of the era produced sound of very low quality unless the performers were stationed directly in front of the primitive recording devices, imposing severe limits on the sort of films that could be created with live-recorded sound.

Competing Systems

By the late 1920s, there existed two contrasting approaches to synchronized sound reproduction, or playback: In 1919, American inventor Lee De Forest was awarded several patents that would lead to the first optical sound-on-film technology with commercial application, where the sound track was photographically recorded on to the side of the strip of motion picture film to create a composite print.[5] If proper synchronization of sound and picture was achieved in recording, it could be absolutely counted on in playback. In parallel, a number of companies were making progress with systems in which movie sound was recorded onto phonograph discs. In this approach, a phonograph turntable is connected by a mechanical interlock to a specially modified film projector, allowing for synchronization. Sound-on-film would ultimately win out over sound-on-disc because of a number of fundamental technical advantages, such as reliable synchronization without further manual adjustment, more efficient possibilities for editing, less complicated distribution, as well as less physical degradation while playing.

Many Premieres

On May 20, 1927, at New York’s Roxy Theater, Fox Movietone presented a sound film of the takeoff of Charles Lindbergh’s celebrated flight to Paris, recorded earlier that day. In the same month, Fox had released the first Hollywood fiction film with synchronized dialogue: the short film They’re Coming to Get Me. After rereleasing a few silent feature hits, such as Seventh Heaven, with recorded music, Fox came out with its first original Movietone feature on September 23: Sunrise, by acclaimed German director F. W. Murnau [6] with a musical score and sound effects. Then, on October 6, 1927, Warner Bros.’ The Jazz Singer premiered, which became a smash box office success. Produced with the Vitaphone sound system, most of the film does not contain live-recorded audio. When the movie’s star, Al Jolson, sings, however, the film shifts to sound recorded on the set, including both his musical performances and two scenes with ad-libbed speech — one of Jolson’s character, addressing a cabaret audience and to the piano player in the band that accompanies him. The first synchronized text occurs at the 17:25 mark of the film:

“Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothin’ yet….“.

Though the success of The Jazz Singer was due largely to Jolson, already established as one of America’s biggest music stars, and its limited use of synchronized sound hardly qualified it as an innovative sound film, the movie’s profits were proof enough to the industry that the new technology was worth investing in.

Let’s go to the movies (1948), [9]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] The Jazz Singer at the Internet Movie Database

- [2] The Jazz Singer Premier Vitaphone Promo

- [3] The Bibliography of Film Sound History

- [4] The Story of Sound Motion Pictures

- [5] Enabling Radio Broadcast of Sound – Lee De Forest and the Audion, SciHi Blog

- [6] Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and the Expressionism in German Cinema, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Jazz Singer at Rotten Tomatoes

- [8] The Jazz Singer at Wikidata

- [9] Let’s go to the movies (1948), RKO Radio Pictures – Anderson, Warner – Copyright Collection (Library of Congress) – Gladden, Tholen – Instructional Films – Teaching Film Custodians – Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Video Archives @ youtube

- [10] Carringer, Robert L. (1979). The Jazz Singer. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- [11] Gomery, Douglas (2005). The Coming of Sound: A History. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

- [12] Timeline of Transitional Sound Films, via Wikidata and DBpedia