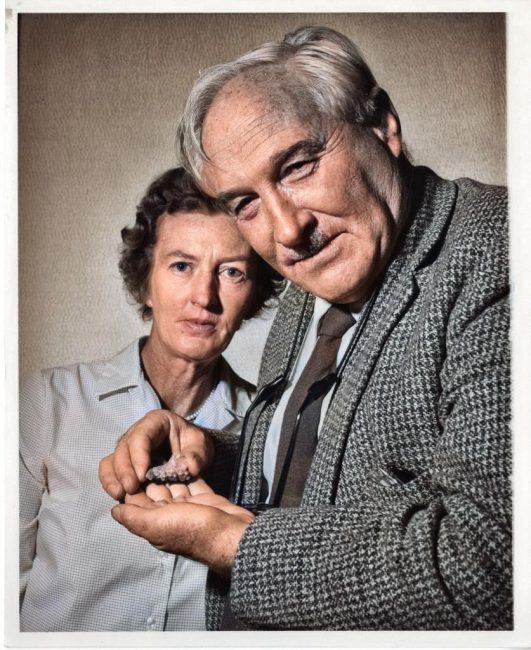

British archeologist and anthropologist Mary Douglas Nicol Leakey (1913-1996) and her husband Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (1903-1972), 1962. Acc. 90-105 – Science Service, Records, 1920s-1970s, Smithsonian Institution Archives

On August 7, 1903, Kenyan paleoanthropologist and archaeologist Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey was born. Louis Leakey‘s work was important in establishing human evolutionary development in Africa, particularly through his discoveries in the Olduvai Gorge. We’ve already had posts about his wife Mary Leakey, as well as two other famous women, whose life is connected with Louis Leakey: Dian Fossey and Jane Goodall. Having been a prime mover in establishing a tradition of palaeoanthropological inquiry, Louis Leakey was able to motivate the next generation to continue it, notably within his own family.

“We know from the study of evolution that, again and again, various branches of animal stock have become over-specialized, and that over-specialization has led to their extinction. Present-day Homo sapiens is in many physical respects still very unspecialized … But in one thing man, as we know him today, is over-specialized. His brain power is very over-specialized compared to the rest of his physical make-up, and it may well be that this over-specialization will lead, just as surely, to his extinction. … if we are to control our future, we must first understand the past better.”

— Louis Leakey, Adam’s Ancestors, (1934)

Born in British East Africa

Born of British missionary parents Harry and Mary Bazett Leakey in British East Africa, Leakey spent his youth with the Kikuyu people of Kenya, about whom he later wrote. His parents hired English tutors for their children, but mostly Louis spent his childhood hunting and trapping with the local Kikuyu boys. Louis spoke Kikuyu as a native language and went through initiation rites with his Kikuyu peers.[3] Leakey matriculated at the University of Cambridge, his father’s alma mater, in 1922, intent on becoming a missionary to British East Africa. He began his archaeological research in East Africa in 1924 with a fossil-hunting expedition run by the British Museum of Natural History, but after his return switched studies to anthropology and graduated in 1926. During the first half of the 20th century, anthropologists considered Asia, or perhaps Europe, to be the birthplace of humans about 60,000 years ago. That’s where all of the hominid fossils had been found.

Nevertheless, Leakey returned to Africa for an new campaign. In 1927, he met Frida Avern at Lake Elmenteita, who he married in 1928. Leakey obtained a research fellowship at St. John’s College and returned to Cambridge in 1929 to do post-graduate work and to classify and prepare the finds from Elmenteita. While cleaning two skeletons he had found he noticed a similarity to one found in Olduvai Gorge by German archeologist Hans Reck. In 1913 Reck had extricated a skeleton from the gorge wall and argued that it must have the date of the bed, which was believed to be 600,000 years. The public was not ready for this news because it was against the general belief at that time. In 1930, Leakey finished his PhD and in November, 1931, led an expedition to Olduvai, including Reck. They verified the provenance of the 1913 find, now Olduvai Man. Non-humanoid fossils and tools were extracted from the ground in large numbers. Back in Cambridge, the skeptics were not impressed. To find supporting evidence of the antiquity of Reck’s Olduvai Man, Louis returned to Africa, excavating at Kanam and Kanjera. He easily found more fossils, which he named Homo kanamensis. On his return Leakey’ finds were carefully examined and tentatively accepted as valid.

The Scandal

At a dinner party, Louis Leakey made the acquaintance of twenty-year-old Mary Nicol, which should turn into a romance. In 1934, Leakey left his wife Frida. A panel at Cambridge investigated his morals and research grants dried up, but his mother raised enough money for subsequent expeditions. As his previous work was questioned by P. G. H. Boswell, Leakeay invited him to verify the sites for himself. Unfortunately, they found that the iron markers Leakey had used to mark the sites had been removed by the Luo tribe for use as harpoons and the sites could not now be located. Boswell immediately set out to publish an article in Nature dated 9 March 1935, destroying Reck’s and Louis’ dates of the fossils and questioning Louis’ competence. The scandals over his personal life and the Kanam and Kanjera fiascos effectively destroyed Louis’ promising academic career at Cambridge. Without a steady job, he got a small income from speaking and writing, and in 1937 he returned to Africa together with Mary to do a massive ethnological study of the Kikuyu tribe. [2]

In 1941 Leakey was nominated an honorary curator of the Coryndon Museum (later the Kenya National Museum), and in 1945 he accepted a poorly paid position as curator of the museum so that he could continue his paleontological and archaeological work in Kenya. In 1947, Louis organized the first Pan-African Congress of Prehistory, a successful event which helped restore his reputation and introduced many scientists to the large amount of important work that the Leakeys had accomplished since the Kanam/Kanjera debacle.[2] The Leakey’s first important African discovery was the skull of a Miocene hominoid in 1948, which Louis named Proconsul africanus. It is now believed that this ape-like creature lived from approximately 23 to 14 million years ago and was likely a common ancestor of both humans and other primate species.[3]

Louis Leakey’s Discoveries in Africa

In 1959 Mary Leakey uncovered a fossil hominin that was given the name Zinjanthropus (now generally regarded as a form of Paranthropus, similar to Australopithecus) and was believed to be about 1.7 million years old.[5] Leakey later theorized that Zinjanthropus was not a direct ancestor of modern man. He claimed this distinction for other hominin fossil remains that his team discovered at Olduvai Gorge in 1960–63 and that Leakey named Homo habilis. Leakey held that Homo habilis lived contemporaneously with Australopithecus in East Africa and represented a more advanced hominin on the direct evolutionary line to Homo sapiens. Initially many scientists disputed Leakey’s interpretations and classifications of the fossils he had found, although they accepted the significance of the finds themselves. [4] They contended that Homo habilis was not sufficiently different from Australopithecus to justify a separate classification. At Fort Ternan in 1962, Leakey’s team discovered the remains of Kenyapithecus, another link between apes and early man that lived about 14 million years ago.

During his final years Leakey became famous as a lecturer in the United States and United Kingdom. He brought audiences cheering to their feet. He did not personally excavate any longer, as he was crippled with arthritis, for which he had a hip replacement in 1968. In the last few years Leakeys’ health began to fail more seriously. Louis Leakey died of a heart attack on 1 October 1972.

Louise Leakey, Provost Lecture: Louise Leakey – A Search for Human Origins at Lake Turkana in Northern Kenya, [7]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Lucy and the Leakeys at Khan Academy

- [2] Louis Leakey at talk biographies.org

- [3] Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey at Leakey.com

- [4] Louis Leakey at Britannica Online

- [5] Mary Leakey and the Discovery of the false ‘Nutcracker Man’, SciHi Blog, 17 June, 2018

- [6] Louis Leakey at Wikidata

- [7] Louise Leakey, Provost Lecture: Louise Leakey – A Search for Human Origins at Lake Turkana in Northern Kenya, Stoney Brook University @ youtube.

- [8] Roger Lewin, “The Old Man of Olduvai Gorge”, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2002.

- [9] Virginia Morell, Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind’s Beginnings, 1995.

- [10] Timeline of Paleoanthropologists, via DBpedia and Wikidata

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 03, Vol. #52 | Whewell's Ghost