Gustave Doré (1832 – 1883), photography by Nadar

On January 6, 1832, French artist, printmaker, illustrator and sculptor Gustave Doré was born. Doré is primarily known for his wood engravings and illustrations of literary works such as Dante’s inferno, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Cervantes’ Don Quixote or the Bible.

Gustave Dorè – the Boy Genius

Gustave Doré was born in Strasbourg, France, the son of Pierre Louis Christophe Doré, engineer of the Ponts et Chaussées, and of Alexandrine Marie Anne Pluchart. Doré’s talent as a draughtsman was already apparent when he was still a student. In addition, he began to play several instruments at the age of seven, including the violin, which he subsequently mastered with virtuosity. At the age of nine he tried his hand at illustrating Dante Alighieri‘s Divine Comedy for the first time.[4] It is believed that his mother was immediately convinced of his abilities while his father, who was an engineer, wanted Gustave to pursue a more practical education. At the age of about 15, he increased his interest in caricatures and comic magazines. When he began drawing his own works and showing them to a publisher, he was immediately contracted for three years in Paris for the Journal pour rire. The 15 year old boy moved in with Monsieur Philipon and became one of the highest paid illustrators in France in the next year. He became well known as the “Boy Genius” and published his first book in this year Les Travaux d’Hercule (The Adventures of Hercules, 1847), published by Aubert in Paris, with all text written by Doré, who also did all of the drawings and engraved them on stone. [1,2]

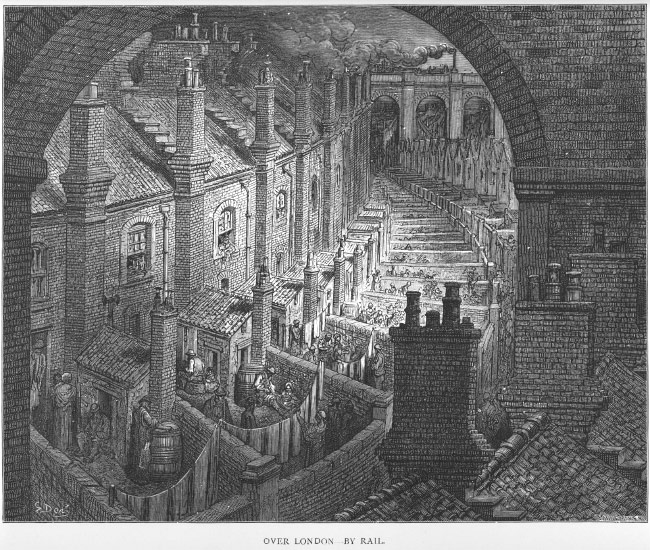

Over London – by Rail from London: A Pilgrimage (1872)

A Master of Caricature

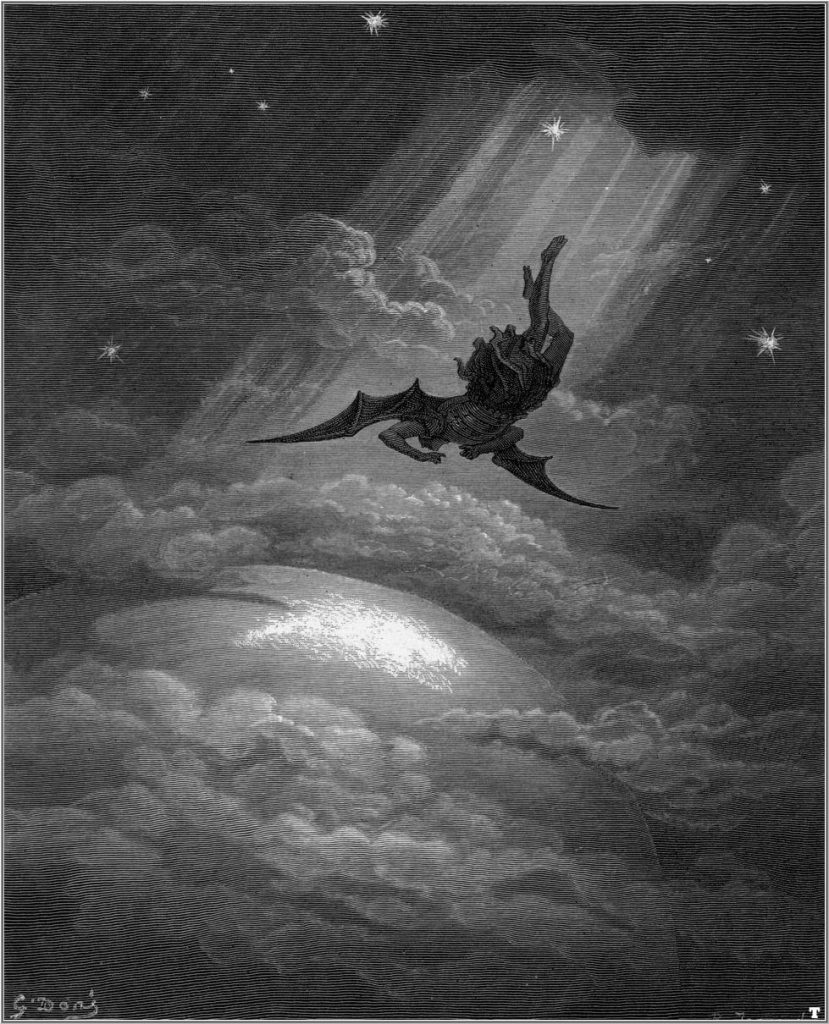

While still being a teenager, Doré managed to complete about 2000 caricature engravings, mostly of satirical nature. Probably in the mid 1850s he increased his enthusiasm in the field of literary engravings and accomplished numerous literary works. Doré subsequently went on to win commissions to depict scenes from books by Cervantes,[6] Rabelais, Balzac,[7] and Milton.[8] He also illustrated “Gargantua et Pantagruel” in 1854. In 1853 Doré was asked to illustrate the works of Lord Byron.[9] This commission was followed by additional work for British publishers, including a new illustrated Bible. In 1856 he produced 12 folio-size illustrations of The Legend of The Wandering Jew, which propagated longstanding antisemitic views of the time, for a short poem which Pierre-Jean de Béranger had derived from a novel of Eugène Sue of 1845.

Success! Come quickly! I am an Ass!

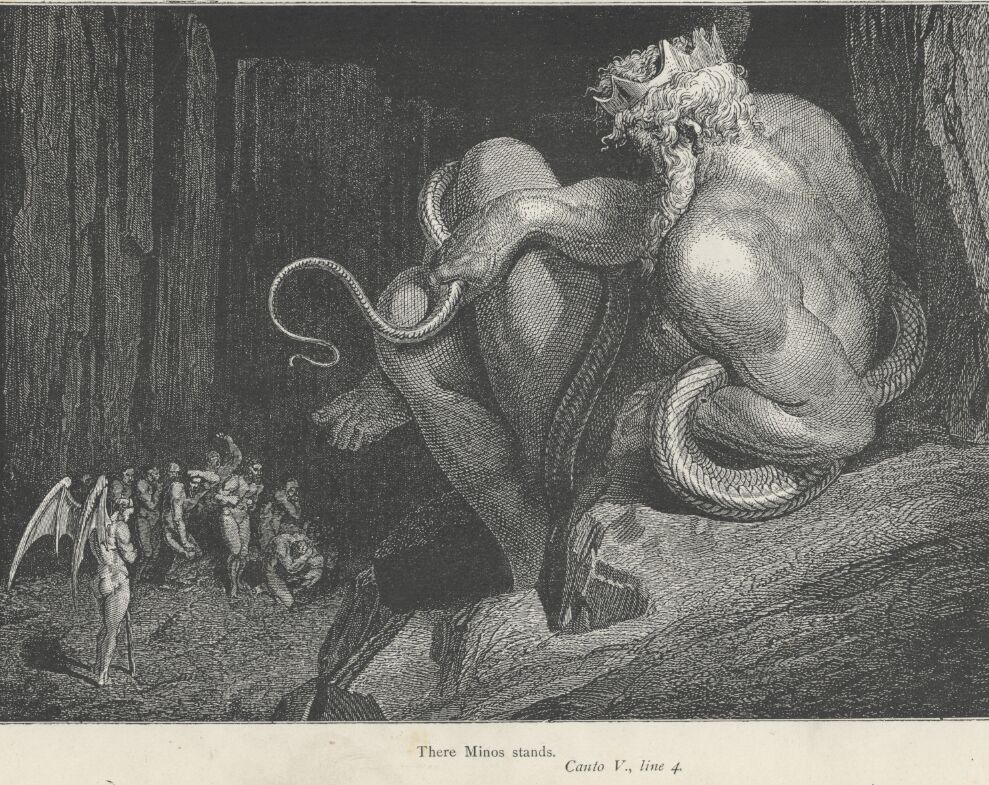

In this period, Doré worked with the leading French publisher Hachette. The artist wanted to produce an ultimate art book, a giant literary folio of Dante’s Inferno and he proposed that the work would sell for 100 Francs even though no book by Doré had retailed for more than 15 Franc previously. The publisher tried to persuade Doré that this was nonsense and at first only 100 copied were bound in order to not waste too much money in the end. The work came out in 1861 and Hachette sent the artist a telegram saying: “Success! Come quickly! I am an ass!“. In 1863 Doré procured the illustration for the French edition of Miguel de Cervantes‘ Don Quixote, for which he produced 370 pictures. From then on, his work influenced artists of various genres.

Minos stands in judgement in Dante’s Inferno Canto 5 line 4 as drawn by Gustave Doré 1861-1865.

Gustave Doré’s Reputation Outside France

In the 1860s, Doré also managed to establish himself outside of France especially in the English-speaking world. When electrotypes became more common, Doré’s works were easier to reproduce and his works were spread even wider. He was quite disappointed when the fine art establishment in France refused to accept him as a painter as he was (later on) believed to be color blind. However, it is also assumed that French artists were afraid he would come to dominate their field as he had illustration, but Doré found his respect in England.

Illustration to John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan descends upon Earth.1866

London and The Raven

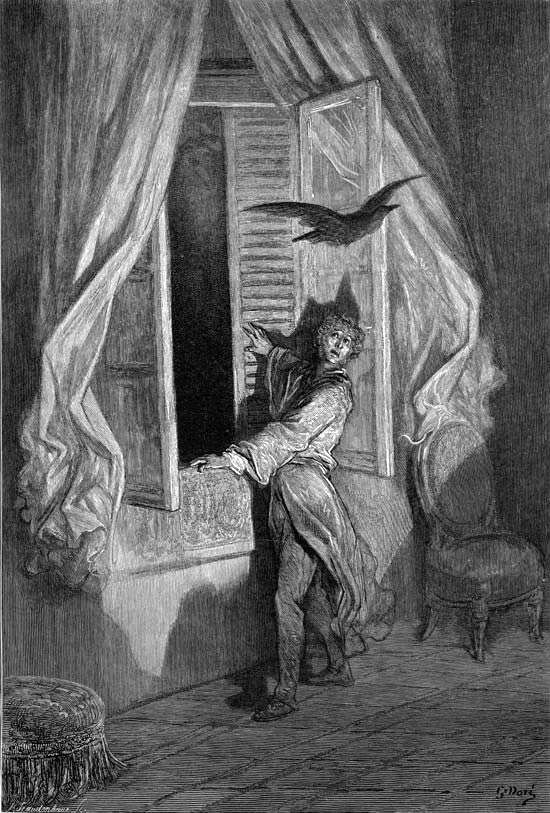

The success of his Bible illustrations of 1866 enabled Doré to hold a major exhibition in London a year later, leading to the founding of the Doré Gallery on Covelant Bond Street. In 1869 the English journalist William Blanchard Jerrold commissioned Gustave Doré to create a comprehensive portrait of London together with him. Doré signed a five-year contract with the publishing house Grant & Co. For the duration of the project, the illustrator was required to spend three months per calendar year in the Empire’s capital, in return for which he received a huge sum of £10,000 each year. In 1872 the book entitled London: A Pilgrimage was published. It contains 180 engravings, which were sold commercially successfully, but were also subjected to harsh criticism. Most critics accused Doré of focusing mainly on the poor quarters and thus on the proletariat. Nevertheless, the artist received numerous follow-up commissions in Great Britain. In 1882, he took on his only U.S. commission for Edgar Allan Poe‘s The Raven and he passed away just as he finished the works on January 23, 1883 after a heart attack.[3] The artist was only 51 years old and left behind an impressive oeuvre with several thousand individual pieces.

Gustave Doré, Illustration 14 for “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe for the line “Not the least obeisance made he.”

Dorè’s Legacy

In 1896, Doré’s works were exhibited in Chicago and they proceeded to break every attendance record at the local Art Institute. In eight months, about 1.5 million people came to see the Doré exhibition while the previous record for attendance at any U.S. art museum for an entire year had been 600,000. [2] Doré’s Bible illustrations are still among the best known of all, and he is considered one of the greatest masters of this genre. Doré’s 230 bible prints were engraved by the famous graphic artists Pisan, Pannemaker and Laplante. He created bizarre depictions of mythical creatures, monsters, skeletons and mysterious mythical figures. The engravings are superbly crafted, the depth effect and the representation of light are masterful. His work had a decisive influence on the surrealist Salvador Dalí, who also oriented his graphic prints to the great themes of world literature.

Philippe Kaenel, L’exposition Gustave Doré (1832-1883). L’imaginaire au pouvoir, [11]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Gustave Doré at Getty Museum

- [2] A Biography of Gustave Doré by Dan Malan

- [3] Quoth the Raven “Nevermore”, SciHi Blog, January 29, 2014.

- [4] Dante Alighieri and the Divine Comedy, SciHi Blog

- [5] Works by or about Gustave Doré at Internet Archive

- [6] Miguel de Cervantes and his Knight of the Sad Countenance, SciHi Blog

- [7] Honoré de Balzac and the Comédie Humaine, SciHi Blog

- [8] John Milton and his great Epic Paradise Lost, SciHi Blog

- [9] Wicked Lord Byron’s Wonderful Poetry, SciHi Blog

- [10] Gustave Doré at Wikidata

- [11] Philippe Kaenel, L’exposition Gustave Doré (1832-1883). L’imaginaire au pouvoir, Musée d’Orsay @ youtube

- [12] Jerrold, Blanchard (1891). The Life of Gustave Doré. London: W. H. Allen & Co., Ltd.(138 illustrations)

- [13] Timeline for Gustave Doré, via Wikidata