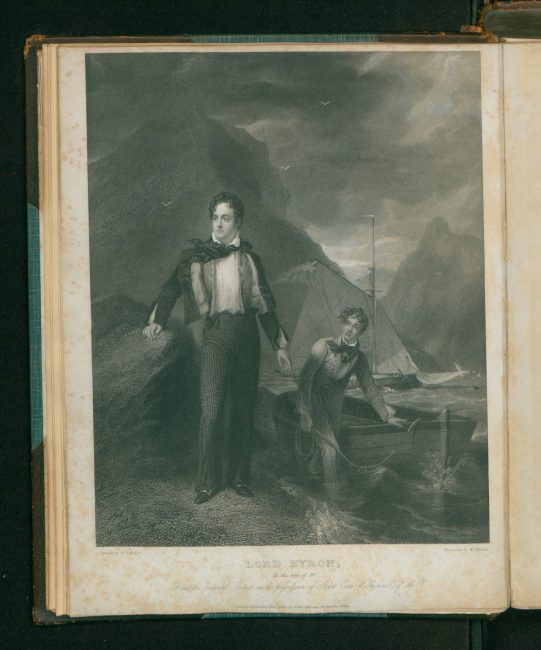

George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824). painted by Thomas Philipps, 1824

On January 22, 1788, George Gordon Noel Byron, 6. Baron Byron of Rochdale, commonly known simply as Lord Byron, English poet and a leading figure in the Romantic movement was born. I remember to have learned about Lord Byron back at school with his lengthy narrative poems like Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage or the shorter and much more beautiful poem “She Walks in Beauty“. Anyway, Byron is considered one of the greatest British poets and remains widely read and influential today.

“I awoke one morning and found myself famous.”

— Lord Byron, Memorandum reference to the instantaneous success of Childe Harold, quoted in [11]

Family Background and Youth

Byron was the son of Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron and his second wife, the former Catherine Gordon. Byron’s father had previously seduced the married Marchioness of Caermarthen and, after she divorced her husband, he married her. His treatment of her was described as “brutal and vicious”, and she died after having given birth to two daughters, only one of whom survived: Byron’s half-sister, Augusta Leigh. Byron suffered from a deformity of his right foot. He was extremely self-conscious about this from a young age, nicknaming himself le diable boiteux (French for “the limping devil“). He spent his early childhood years in poor surroundings in Aberdeen, where he was educated until he was ten. When Byron’s great-uncle, the “wicked” Lord Byron, died on 21 May 1798, the 10-year-old boy became the 6th Baron Byron of Rochdale and inherited the ancestral home, Newstead Abbey, in Nottinghamshire, and went on to Cambridge, where he piled up debts and aroused alarm with bisexual love affairs. Staying at Newstead in 1802, he probably first met his half-sister, Augusta with whom he was later suspected of having an incestuous relationship.

First Poetry

“Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most

Must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth,

The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life.”

— Lord Byron, Manfred (1817), Act I, scene i.

In 1807 Byron’s first collection of poetry, Hours Of Idleness appeared. The poems were savagely attacked by Henry Brougham in the Edinburgh Review. Byron replied with the publication of his satire, English Bards and Scotch Reviewers in 1809. In 1809 he took his seat in the House of Lords, and set out on his grand tour, where he visited Spain, Malta, Albania and Greece. His poetical account of this grand tour, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812), an exotic travelogue spiced with romantic disillusionment, earned Byron instant glory and established him as one of England’s leading poets. The first edition was sold out in three days only. Byron was renowned for his personal beauty, which he enhanced by wearing curl-papers in his hair at night. He was athletic, being a competent boxer and horse-rider and an excellent swimmer. While his fame was spreading, Byron was busy shocking London high society by starting an affair with Lady Caroline Lamb and was ostracized when he was suspected of having a sexual relationship with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, who gave birth to an illegitimate daughter.

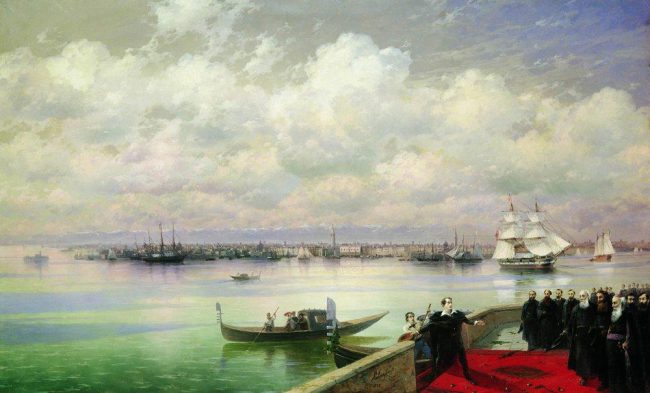

Byron’s visit to San Lazzaro as depicted by Ivan Aivazovsky (1899)

The Gothic Adventure

In 1814, Byron’s The Corsair, sold incredible 10,000 copies on the first day of publication. He was married to Annabella Millbanke in January 1815, and she gave birth to their daughter Ada in December [1], but left him in January 1816, obtaining legal separation. Rumours concerning the cause of their separation centered around Byron’s relations with his half sister Augusta Leigh, though it seems clear that the proximate cause was Annabella’s revelation to her nursery governess that Byron had practised sodomy on her. After the separation, Byron went abroad, never returning to England again. He was now the most famous exile in Europe. After visiting the battlefield of Waterloo, Byron journeyed to Switzerland. At the Villa Diodati, near Geneva, he was on friendly terms with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his entourage [2], which included Shelley’s wife Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and Claire Clairmont [3], who had begun an affair with Byron before he left England. At the end of the summer the Shelley party left for England, Claire carrying Byron’s illegitimate daughter. A tour of the Bernese Oberland with Hobhouse provided the scenery for Manfred, a Faustian poetic drama that reflected Byron’s brooding sense of guilt and remorse.

The Greek Adventure

In April 1823 the London Greek Committee contacted Byron with a view to acting as its agent in helping the Greeks with their War of Independence from the Ottomans, which Byron immediately accepted. Arriving in Greece, he used £4000 (about £200,000 in modern terms) of his own funds to enable part of the Greek fleet to relieve Missolonghi, which was in a state of blockade, then sailed for Missolonghi himself in December, joining enthusiastically in the plans to attack the Turkish held fort at Lepanto. But in February he had a fit and on April 19, 1824 he died. His body was embalmed. The heart was removed and buried in Missolonghi, and his remains were then sent to England, and buried near Newstead Abbey, having been refused burial in Westminster Abbey.

Lord Byron, in Letters and Journals (1830)

Alfred Tennyson would later recall the shocked reaction in Britain when word was received of Byron’s death. The Greeks mourned Lord Byron deeply, and he became a hero. The national poet of Greece, Dionysios Solomos, wrote a poem about the unexpected loss, named To the Death of Lord Byron. In 1969, 145 years after Byron’s death, a memorial to him was finally placed in Westminster Abbey.

“A great poet belongs to no country; his works are public property, and his Memoirs the inheritance of the public.”

— Lord Byron, As quoted in [12]

The Byronic Hero

The figure of the Byronic hero pervades much of his work, and Byron himself is considered to epitomize many of the characteristics of this literary figure. Scholars have traced the literary history of the Byronic hero from John Milton,[4] and many authors and artists of the Romantic movement show Byron’s influence during the 19th century and beyond, including the Brontë sisters. His philosophy was more durably influential in continental Europe than in England; Friedrich Nietzsche admired him, and the Byronic hero was echoed in Nietzsche’s superman.[5] he Byronic hero presents an idealized, but flawed character whose attributes include: great talent; great passion; a distaste for society and social institutions; a lack of respect for rank and privilege (although possessing both); being thwarted in love by social constraint or death; rebellion; exile; an unsavory secret past; arrogance; overconfidence or lack of foresight; and, ultimately, a self-destructive manner. These types of characters have since become ubiquitous in literature and politics.

Jonathan Bate, Byron and the Age of Sensation, [12]

Related work and further Reading:

- [1] Ada Lovelace – The World’s Very First Programmer, SciHi Blog, November 27, 2012.

- [2] Gothic – The Life and Works of Percy Bysshe Shelley, SciHi Blog, July 8, 2012.

- [3] Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, the Mother of the Monster, SciHi Blog, August 30, 2012.

- [4] John Milton and his great Epic Paradise Lost, SciHi Blog, December 9, 2012.

- [5] God is Dead – The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, SciHi Blog, Oct 15, 2012.

- [6] Lord Byron at Encyclopædia Britannica

- [7] Works by Lord Byron at Project Gutenberg

- [8] The Byron Society

- [9] Lord Byron at Wikidata

- [10] Christensen, Jerome (1993). Lord Byron’s Strength: Romantic Writing and Commercial Society. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- [11] Eisler, Benita (1999). Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- [12] Jonathan Bate, Byron and the Age of Sensation, Gresham College @ youtube

- [13] Galt, John (1830). The Life of Lord Byron. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley.

- [14] Marchand, Leslie A., ed. (1982). Lord Byron: Selected Letters and Journals. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press

- [15] Timeline for Lord Byron, via Wikidata

“Ah, from daylight though thou perish,

Ne’er a heart will let thee go!

Scarce we venture to bewail thee,

Envying we sing thy fate:

Did sunshine cheer, or storm assail thee,

Song and heart were fair and great.

Earthly fortune was thy dower,

Lofty lineage, ample might,

Ah, too early lost, thy flower

Wither’d by untimely blight!

Glance was thine the world discerning,

Sympathy with every wrong,

Woman’s love for thee still yearning,

And thine own enchanting song…”