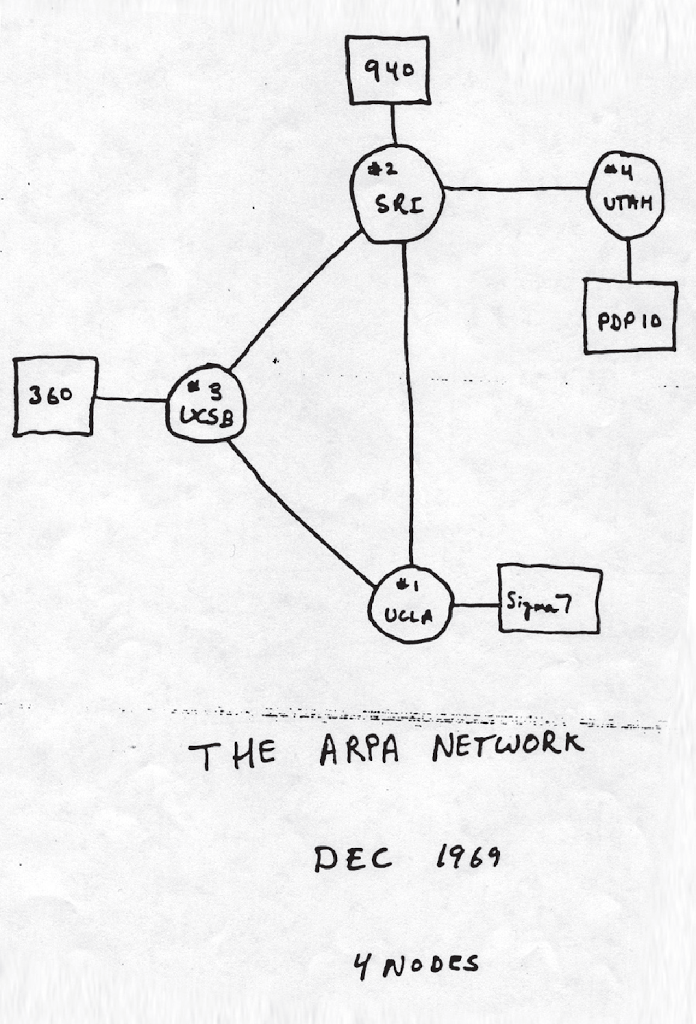

The first nodes of the ARPANET

On October 29, 1969, the very first message between two distant computer nodes, from the Network Measurement Center at the UCLA’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and SRI International (SRI) was sent. This is to be considered the birth of the ARPANET, which should become the Internet.

Origins of the Internet

What was the reason for the development of the Internet? Especially in the 1960s, when computers were absolutely not widespread or ubiquitous as today. Moreover, computers in the 1960s did not follow the same or similar hardware and software architecture. This means that for two computers to communicate, a special translation interface must be constructed either way by hardware and by software. On the other hand, we are in the 1960s. In the late 1940s, Thomas Watson, founder of IBM stated “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.” We know that he was wrong. But, there were only a few computers around concentrating on research laboratories, universities, or working for the military. The founding myth of the internet always refers to the so called “Sputnik Shock” as being the initial event. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet launched the very first satellite into orbit. Thus, proving that they were also able to reach the USA with their ballistic missiles. This first strike capability gave them a significant advantage in the times of Cold War. US president Eisenhower in response founded the ARPA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency, to catch up the Soviet’s military and scientific advantage. One of the many projects being founded by ARPA was also computer network communication. Something exotic, considering the times and the circumstances. But, nevertheless, in times of potential nuclear thread it seemed not to be difficult to come up with an argument to support also the funding of more or less ‘esoterical’ technologies.

Packet Switching

For this reason you might read that the internet was developed as response to he Soviet nuclear threat to enable fault tolerant computer network communication that will also work when parts of the communication network might get destroyed by a nuclear blast (or something else). The internet’s fault tolerance really is something extraordinary, compared to the previous switching networks that failed, whenever some relay station went out of service and the network traffic had to be explicitly rerouted. The internet is based on the principle of packet switching. Thus, contrariwise to the way traditional telephone services are working – i.e. a connection between sender and receiver is established and along the switched connection the entire message is transferred, blocking the communication for other parties until the message is received completely – packet switching splits the message in small packets that are sent independently over various routes within the network. This has several advantages: First, a connection is only blocked for the time one small packet needs to travel from sender to receiver. Other users might also send their packets in between the packets from the original sender. Second, if a packet got lost, only the packet has to be re-transmitted instead of the entire message. Thus making network communication more efficient. The principle of packet switching was already developed by Paul Baran from RAND Corporation in 1959.

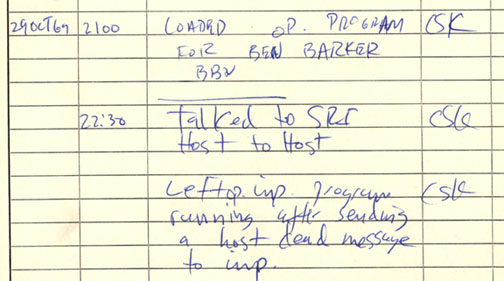

First ARPANET IMP log: the first message ever sent via the ARPANET, 10:30 pm PST on 29 October 1969 (6:30 UTC on 30 October 1969)

Early Computer Network Ideas

The earliest ideas for a computer network intended to allow general communications among computer users were formulated by J. C. R. Licklider of Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), in April 1963, in memoranda discussing his concept for an “Intergalactic Computer Network“. Those ideas contained almost everything that composes the contemporary Internet. In October 1963, Licklider was appointed head of the Behavioral Sciences and Command and Control programs at the Defense Department‘s Advanced Research Projects Agency — ARPA (the initial ARPANET acronym). He then convinced Ivan Sutherland and Bob Taylor that this computer network concept was very important and merited development, although Licklider left ARPA before any contracts were let that worked on this concept. Ivan Sutherland and Bob Taylor continued their interest in creating such a computer communications network, in part, to allow ARPA-sponsored researchers at various corporate and academic locales to put to use the computers ARPA was providing them, and, in part, to make new software and other computer science results quickly and widely available. In his office, Taylor had three computer terminals, each connected to separate computers, which ARPA was funding: the first, for the System Development Corporation (SDC) Q-32, in Santa Monica

“For each of these three terminals, I had three different sets of user commands. So, if I was talking online with someone at S.D.C., and I wanted to talk to someone I knew at Berkeley, or M.I.T., about this, I had to get up from the S.D.C. terminal, go over and log into the other terminal and get in touch with them. I said, “Oh Man!”, it’s obvious what to do: If you have these three terminals, there ought to be one terminal that goes anywhere you want to go. That idea is the ARPANET“.

The problem remains that for connecting a number of computers of various architectures, you need one dedicated interface between each pair of connected computers. Thus, for 4 computers, you will need 6 interfaces, for 5 computers, you will need 10, for 6 computers, you will need 15, for 10 computers you will need 45 and for 100 computers even 4,950 interfaces. The growth of the number of required interfaces would be quadratic. Therefore, Robert Taylor developed the following plan: a network composed of small computers called Interface Message Processors (IMPs: today called routers), that functioned as gateways interconnecting local resources. At each site, the IMPs performed store-and-forward packet switching functions, and were interconnected with modems that were connected to leased lines, initially running at 50kbit per second. The host computers were connected to the IMPs via custom serial communication interfaces. In this way, communication was performed in a subnetway and only for each hardware architecture exactly one interface had to be developed to connect to the subnetway.

“Login”

The first four computers connected to the now called ARPANET were an SDS Sigma 7 from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), an SDS 940 from the Stanford Research Institute’s Augmentation Research Center, an IBM 360 75 from University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), and a DEC PDP-10 from University of Utah‘s Computer Science Department. The first message on the ARPANET was sent by UCLA student programmer Charley Kline, at 10:30 pm on 29 October 1969, from Boelter Hall 3420. Kline transmitted from the university’s SDS Sigma 7 Host computer to the Stanford Research Institute’s SDS 940 Host computer. The message text was the word login.

Computer Networks – The Heralds Of Resource Sharing (Arpanet, 1972), [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Kleinrock, Leonard. “The Day the Infant Internet Uttered its First Words“. UCLA.

- [2] Internet Milestones

- [3] Ch. Meinel, H. Sack: Internetworking: Technological Foundations and Applications, Springer (2013)

- [3] How the ARPANET became the Internet, SciHi Blog

- [4] Ivan Sutherland – Well, I Didn’t Know it was Hard, SciHi Blog

- [5] The Sputnik Shock, SciHi Blog

- [6] Jon Postel – Editor in Chief of the Internet, SciHi Blog

- [7] The Publication of the First RFC, SciHi Blog

- [8] Computer Networks – The Heralds Of Resource Sharing (Arpanet, 1972), via the Internat Archive, Brandon Goodrich @ youtube

- [9] “ARPANET – The First Internet”. Living Internet.

- [10] Hafner, Katie; Lyon, Matthew (1996). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet. Simon and Schuster.

- [11] ARPANET at Wikidata

- [12] Timeline “History of the Internet” via DBpedia & Wikidata