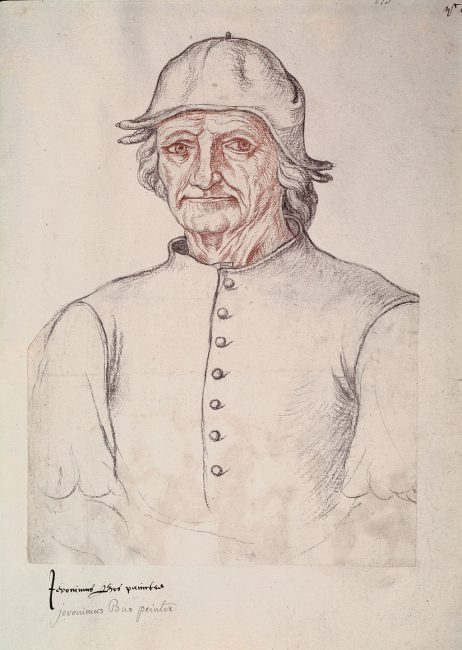

Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516)

On 9 August 1516, Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch was buried. One of the most notable representatives of the Early Netherlandish painting school, his work, generally oil on oak wood, mainly contains fantastic illustrations of religious concepts and narratives. Today, Bosch is seen as a hugely individualistic painter with deep insight into humanity’s desires and deepest fears.

Hieronymus Bosch – Background

Hieronymus Bosch came from the painter family “van Aken”, whose name of origin indicates that the direct ancestors in the paternal line came from the Imperial city of Aachen, today Germany. Four generations of painters are attested: Hieronymus Bosch’s great-grandfather Thomas van Aken was active as a painter in Nijmegen. His grandfather Jan van Aken moved from Nijmegen to the up-and-coming city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch around 1426. He crowned his social advancement in 1462 with the purchase of a stone house directly on the market square, to which he also moved his painter’s workshop. Four of Jan’s five sons, including Hieronymus’ father Anthonius van Aken, also became painters. Anthonius had five children: two daughters (one was named Herberta) and the three sons: Goeswinus or Goessen van Aken, Jan van Aken and, as the fifth child, Jheronimus van Aken (Hieronymus). Hieronymus later named himself after his hometown, which is also called Den Bosch. In Spain, where some of his most important paintings are exhibited in the Museo del Prado, they speak of El Bosco.

The Artist’s Life

Like his two older brothers, Hieronymus followed the family tradition and, like them, received his painter’s training at least for a time in his father’s workshop. After his father’s death, Goessen continued the workshop as the eldest son. Hieronymus Bosch was first mentioned in a document in 1474. In 1481 he married the patrician daughter Aleyt Goyaert van de Mervenne, who brought a house and an estate into the marriage. This helped Bosch to become more independent. In 1488, he joined the religious confraternity of Our Lady of the local St. John’s Cathedral, first as an outer, then as a sworn member. The elite inner circle of the brotherhood comprised about 60 people, usually from the highest aristocratic or patrician urban class, and almost all of them were clergymen of various degrees of ordination. Almost half of them were secular priests, some of whom were also notaries. There were also doctors and pharmacists among them, as well as a few artists: musicians, an architect and only one painter – Hieronymus Bosch. The brotherhood maintained contact with the highest circles of the nobility, the clergy and the urban elites in the Netherlands. Besides this political-social side, they were equally religiously oriented and were supervised by the Dominicans. They met once a month for meals, twice a week for mass. St. John’s, St. Mary’s and other feast days were celebrated by spiritual games and processions. Bosch found his patrons in the ranks of the brothers and through their contacts with the higher nobility. In addition to the Brotherhood of Our Lady, he worked for the urban elite and the Dutch high nobility. Among his most important clients were the reigning Prince of the Netherlands Archduke Philip the Fair and his court. Bosch died in his hometown in 1516 at the age of 66. A funeral mass served in his memory was held in the church of Saint John on 9 August of that year.

An Enigmatic Style and Fantastic Topics

Hieronymus Bosch lived in the age of the Renaissance, a period of economic awakening, princely power politics and the demand for religious and moral renewal. In his paintings, he subjected all estates to criticism, not just the clergy. Bosch often painted religious motifs and themes. Triptychs such as The Hay Cart and The Garden of Delights, on the other hand, were clearly not intended for an altar, but to impress and entertain a courtly audience. His work defies easy interpretation: while there are some plausible interpretations of his works, many depictions have remained enigmatic or the interpretation disputed. Bosch himself left no written record of his works. He painted mostly with oil paints, rarely with tempera, on oak wood. His palette was not very rich in many paintings. He used azurite for the sky and landscapes in the background, green glazes and copper-containing pigments (malachite and copper(II) acetate (verdigris)) for foliage and landscapes in the foreground, and lead-tin yellow, ochre, and red lacquer (carmine or dyer’s madder) for the important elements of the picture. Bosch’s paintings were done in a variety of colors.

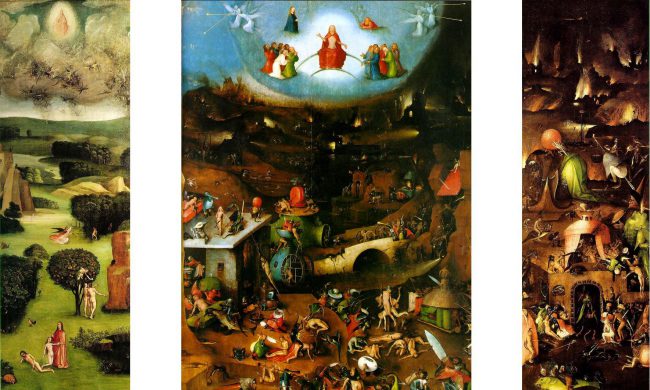

The Garden of Earthly Delights in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, c. 1495–1505, attributed to Bosch.

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Bosch’s most famous triptych is The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1495–1505) whose outer panels are intended to bracket the main central panel between the Garden of Eden depicted on the left panel and the Last Judgment depicted on the right panel. In the left hand panel God presents Eve to Adam; innovatively God is given a youthful appearance. The figures are set in a landscape populated by exotic animals and unusual semi-organic hut-shaped forms. The central panel is a broad panorama teeming with nude figures engaged in innocent, self-absorbed joy, as well as fantastical compound animals, oversized fruit, and hybrid stone formations. The right panel presents a hellscape; a world in which humankind has succumbed to the temptations of evil and is reaping eternal damnation. Set at night, the panel features cold colours, tortured figures and frozen waterways. The nakedness of the human figures has lost any eroticism suggested in the central panel, as large explosions in the background throw light through the city gate and spill onto the water in the panel’s midground. In recent decades, scholars have come to view Bosch’s vision as less fantastic, and accepted that his art reflects the orthodox religious belief systems of his age. His depictions of sinful humanity and his conceptions of Heaven and Hell are now seen as consistent with those of late medieval didactic literature and sermons.

The Last Judgment. circa 1482-1516

Signs and Symbols

What has survived of Bosch’s works are primarily paintings on wooden panels, along with some drawings on paper. He used the same symbols again and again in many of his paintings, the meaning of which has been handed down today partly through texts, partly by comparing his works with others. About this symbolism or iconography there is a multitude of philological and art historical studies, some of them very extensive.

- The bear stands for the deadly sin “anger”.

- The toad – it usually squats on a person – stands for “depravity”. If it squats on the genitals, this is seen as an allusion to the mortal sin “lust”; if it squats on the chest or face, this can also be an allusion to the mortal sin “arrogance” (pride, conceit).

- The funnel, usually inverted on a person’s head, stands for “meanness, deceitful intent” (the wearer of the funnel has shielded himself from heaven, the eye of God).

- The arrow also signals evil, sometimes it is stuck crosswise in the persons hat or cap, sometimes it pierces the bodies, sometimes it is stuck in the anus of a half-naked person (which is also an allusion to “depravity”).

- The jug is often in combination with a stick, sometimes it is impaled directly on it. It is a sexual allusion, suggesting “lust”. The same applies to the barrel with the bung, also often found in combination with a stick.

- The bagpipe is also an allusion to the deadly sin “lust”.

- In Christian paintings, the owl cannot be interpreted in the ancient-mythological sense as a symbol of wisdom. Bosch has placed the owl in many paintings, he sometimes puts it in the context of people who behave insidiously or fall into a mortal sin. Therefore, it is often assumed that as a night animal and bird of prey, it stands for evil and symbolizes folly, spiritual blindness and the ruthlessness of everything earthly.

The interpretation of symbols depends very much on their respective pictorial context, so that a positive symbol such as the swan, which in the context of Mary signifies purity and chastity, can mean the opposite in other pictorial contexts. Thus, on a flag, it adorns a house that is clearly identified as a brothel by other symbols.

Ascent to Heaven . circa 1500-1504

Fantastic Creatures and Where to Find them…

Many of Bosch’s paintings incorporate demonic figures and mythical creatures. Human beings with animal heads of fish, birds, pigs or predators also appear, ugly gnomes and monsters populate the pictures. They torture defenseless people or lead them to perdition. The depiction of mythical creatures was nothing unusual in the Middle Ages, it occurred in the so-called bestiaries. The bestiary developed from the Physiologus, a mythological “animal lore book” originating in Alexandria (Egypt), which found its way to Europe in the early Middle Ages and was translated. Bestiaries are allegorical animal books that describe real and fantastic animals and seek to typify their real or supposed characteristics. They served as didactic media for instruction in morals and religion and were very popular because people could learn about exotic animals from other continents only through these books. But mythical animals such as the unicorn or the dragon also found their way into such works. Because Bosch was such a unique and visionary artist, his influence has not spread as widely as that of other major painters of his era. However, there have been instances of later artists incorporating elements of The Garden of Earthly Delights into their own work. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569) in particular directly acknowledged Bosch as an important influence and inspiration,[4] and incorporated many elements of the inner right panel into several of his most popular works.

Joseph Leo Koerner, The Unspeakable Subject of Hieronymus Bosch, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Jheronimus Bosch Art Center

- [2] Hieronymus Bosch – The complete works, 188 works by Bosch

- [3] Bosch, the Fifth Centenary Exhibition: At the Prado

- [4] The Brueghel Family Painting Business, SciHi Blog

- [5] “Bosch and Bruegel: Inventions, Enigmas and Variations. The National Gallery, London. Press release archive, November 2003.

- [6] “The Garden of Earthly Delights: A diachronic interpretation of Hieronymus Bosch’s masterpiece” A lecture by Matthias Riedl

- [7] Audiovisual tour of The Garden of Earthly Delights narrated by Redmond O’Hanlon

- [8] Joseph Leo Koerner, The Unspeakable Subject of Hieronymus Bosch, Institute of Advanced Studies @ youtube

- [9] Hieronymus Bosch at Wikidata

- [10] Ilsink, Matthijs; Koldeweij, Jos (2016). Hieronymus Bosch: Painter and Draughtsman – Catalogue raisonné. Yale University Press. p. 504.

- [11] Timeline for Hieronymus Bosch via Wikidata