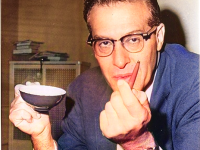

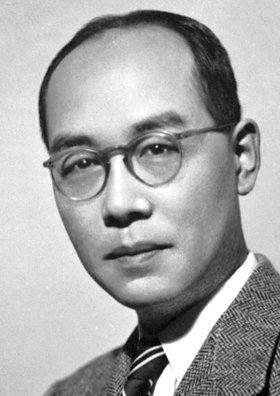

Hideki Yukawa (1907-1981)

On January 23, 1907, Japanese theoretical physicist and the first Japanese Nobel laureate Hideki Yukawa was born. Yukawa shared the 1949 Nobel Prize for Physics for “his prediction of the existence of mesons on the basis of theoretical work on nuclear forces.”

“Reality is cruel. All of the naivete is going to be removed. Reality is always changing, and it is always unpredictable. All of the balance is going to be destroyed.” — Hideki Yukawa

Hideki Yukawa – Early Years

Hideki Yukawa was born as Hideki Ogawa in Tokyo, Japan, among six siblings to his father Takuji Ogawa, who later became Professor of Geology at Kyoto University. His father Takuji Ogawa was the son of a Confucian scholar serving the Tanabe family and Yukawa and his brothers were taught Chinese classics by their grandfather. Yukawa’s mother came from a samurai family (Ogawa) and after the marriage Yukawa’s father, who was originally called Asai, was adopted by the Ogawa family so that they would not die out. Brought up in Kyoto, his father, for a time, considered sending him to technical college rather than university since he was not as outstanding a student as his older brothers. However, by interference of his middle school principal, who praised his high potential in mathematics, his father relented.

Academic Career

In 1929, after receiving his degree from Kyoto Imperial University, he stayed on as a lecturer for four years. His research interest switched to theoretical physics, particularly in the theory of elementary particles. In 1932, he married Sumi Yukawa and In accordance with Japanese customs changed his family name from Ogawa to Yukawa. In 1933 he became an assistant professor at Osaka Imperial University, where he earned his doctorate in 1938. He rejoined Kyōto Imperial University as a professor of theoretical physics (1939–50), held faculty appointments at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey (U.S.), and at Columbia University in New York City, and became director of the Research Institute for Fundamental Physics in Kyōto (1953–70).

The Theory of Mesons

In 1935 he published his theory of mesons, which explained the interaction between protons and neutrons, and was a major influence on research into elementary particles. Yukawa proposed a new theory of the strong and weak nuclear forces in which he predicted a new type of particle as those forces’ carrier particle. He called it the U-quantum, and it was later known as the meson because its mass was between those of the electron and proton. American physicist Carl Anderson’s discovery in 1937 of a particle among cosmic rays with the mass of the predicted meson suddenly established Yukawa’s fame as the founder of meson theory, which later became an important part of nuclear and high-energy physics.[3]

The Nobel Prize in Physics

However, by the mid-1940s, it was discovered that Anderson’s new particle, the muon, could not be the predicted carrier particle. The predicted particle, the pion, was not discovered until 1947 by British physicist Cecil Powell, but, despite Yukawa’s successful prediction of the pion’s existence, it also was not the carrier particle of the nuclear forces, and meson theory was supplanted by quantum chromodynamics.[2,6] In 1949, Yukawa became a professor at Columbia University, the same year he received the Nobel Prize in Physics, after the discovery by Cecil Frank Powell, Giuseppe Occhialini and César Lattes of Yukawa’s predicted pion in 1947.

Quantum Electrodynamics

Although meson theory was Yukawa’s greatest accomplishment, throughout his scientific career he regarded the nuclear force problem as of less importance than that of formulating a mathematically consistent relativistic quantum theory, free of “infinities” like those brought to light in the Heisenberg-Pauli quantum electrodynamics of 1929. Around 1940 he introduced the idea he called “maru” (circle), representing a finite region of an elementary particle within which relativistic causality is not valid. Beginning in 1950, Yukawa developed the idea of nonlocal quantum fields, an idea strongly influenced by Heisenberg’s concept of a fundamental universal length. Like some older physicists, notably Heisenberg and Dirac, Yukawa never fully accepted the renormalization method of quantum electro-dynamics, regarding it as a mere calculational device, a door that concealed the difficulty but at the same time blocked the road to progress. [4]

Later Years

Yukawa also worked on the theory of K-capture, in which a low energy electron is absorbed by the nucleus, after its initial prediction by G. C. Wick. In 1955, he joined ten other leading scientists and intellectuals in signing the Russell–Einstein Manifesto, calling for nuclear disarmament. Yukawa retired from Kyoto University in 1970 as a Professor Emeritus. He died in Kyoto, on 8 September 1981 from pneumonia and heart failure, aged 74.

Leonard Susskind, Lecture 1 | New Revolutions in Particle Physics: Basic Concepts, [8]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Hideki Yukawa, Biographical, at Nobelprize.org

- [2] Hideki Yukawa, Japanese Physicist, at Britannica Online

- [3] Carl David Anderson and the Positron, SciHi blog, January 11, 2014.

- [4] “Yukawa, Hideki.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com

- [5] Hideki Yukawa at Wikidata

- [6] C. F. Powell and the Pion, SciHi Blog, December 5, 2017.

- [7] short film “Yukawa Story (1954)” at the Internet Archive

- [8] Leonard Susskind, Lecture 1 | New Revolutions in Particle Physics: Basic Concepts, Stanford @ youtube

- [9] Kemmer, N. (1983). “Hideki Yukawa. 23 January 1907 – 8 September 1981”. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 29: 660–676.

- [10] Yukawa, H. (1935). “On the Interaction of Elementary Particles” . Proc. Phys.-Math. Soc. Jpn. 17 (48).

- [11] Timeline for Hideki Yukawa, via Wikidata