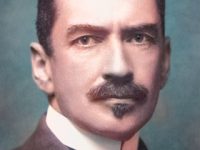

Florence Barbara Seibert (1897-1991)

On October 6, 1897, American biochemist Florence Barbara Seibert was born. Seibert is best known for identifying the active agent in the antigen tuberculin as a protein, and subsequently for isolating a pure form of tuberculin, purified protein derivative (PPD), enabling the development and use of a reliable TB test.

Youth and Education

Seibert was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, USA, the second of three children of George Peter Seibert, a rug manufacturer and merchant, and Barbara (Memmert) Seibert. At age three, Florence contracted polio She had to wear leg braces and walked with a limp throughout her life. With the help of her highly supportive parents, she was able to successfully finish high scholl and entered Goucher College in Baltimore, where she studied chemistry and zoology, graduating in 1918. She and one of her chemistry teachers, Jessie E. Minor, did war-time work at the Chemistry Laboratory of the Hammersley Paper Mill in Garfield, New Jersey. Although Seibert initially wanted to pursue a career in medicine, she was advised against it as it was “too rigorous” in view of her physical disabilities. She decided on biochemistry instead and began graduate studies at Yale University under Lafayette B. Mendel, one of the discoverers of Vitamin A. [2] Seibert earned her Ph.D. in biochemistry from Yale University in 1923. At Yale she studied the intravenous injection of milk proteins and developed a method to prevent these proteins from being contaminated with bacteria.

Florence Seibert then moved on to Chicago to work as a post-graduate fellow under H. Gideon Wells at the University of Chicago. She continued her research on pyrogenic (fever causing) distilled water, and her work in this area acquired practical significance when intravenous blood transfusions became a standard part of many surgical procedures.[2] She was financed by the Porter Fellowship of the American Philosophical Society, an award that was competitive for both men and women. She went on to work part-time at the Ricketts Laboratory at the University of Chicago, and part-time at the Sprague Memorial Institute in Chicago.

Preventing Contamination during the Distillation Process

In 1924, she received the University of Chicago’s Howard Taylor Ricketts Prize for work she began at Yale and continued in Chicago.[8] At Yale she reported a curious finding: intravenous injections often caused fever in patients. Dr. Seibert determined that the fevers were caused by toxins produced by the bacteria. The toxins were able to contaminate the distilled water when spray from the boiling water in the distillation flask reached the receiving flask. Seibert invented a new spray-catching trap to prevent contamination during the distillation process.

Florence Seibert’s Research on Tuberculosis

Seibert served as an instructor in pathology from 1924-28 at the University of Chicago and was hired as an assistant professor in biochemistry in 1928. During this time, she met Esmond R. Long, who was working on tuberculosis. In 1932 she agreed to relocate, with Long, to the Henry Phipps Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. He became professor of pathology and director of laboratories at the Phipps Institute, while she accepted a position as an assistant professor in biochemistry. Their goal was the development of a reliable test for the identification of tuberculosis. The previous tuberculin derivative, Robert Koch’s substance, had produced false negative results in tuberculosis tests since the 1890s because of impurities in the material.

In 1882 Robert Koch had discovered that the tubercle bacillus was the primary cause of tuberculosis. He also discovered that if the liquid on which the bacilli grew was injected under the skin, a small bite-like reaction would occur in people who had been infected with the disease. (Calling the liquid “old tuberculin,” Koch produced it by cooking a culture and draining off the dead bacilli.) Although he had believed the active substance in the liquid was protein, it had not been proven.[2] With Long’s supervision and funding, Seibert identified the active agent in tuberculin as a protein. Seibert spent a number of years developing methods for separating and purifying the protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, obtaining purified protein derivative (PPD) and enabling the creation of a reliable test for tuberculosis.

Her first publication on the purification of tuberculin appeared in 1934. She developed methods for purifying a crystalline tuberculin derivative using filters of porous clay and nitric-acid treated cotton. In the 1940s, Seibert’s purified protein derivative (PPD) became a national and international standard for tuberculin tests. In 1943, Seibert received the first Achievement Award from the American Association of University Women.

Later Life

Florence Seibert remained at the Henry Phipps Institute at the University of Pennsylvania from 1932 until her retirement in 1959, first as an assistant professor from 1932-1937, an associate professor from 1937-1955, a full professor of biochemistry from 1955-1959, and professor emeritus as of her official retirement in 1959. Between 1937 and 1938 she was a Guggenheim fellow in the laboratory of Theodor Svedberg at the University of Upsala in Sweden. Siebert received the Trudeau Medal from the National Tuberculosis Association in 1938, the Francis P. Garvan Medal from the American Chemical Society in 1942, and an induction to the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1990.

Florence Seibert died in St. Petersburg, Florida on August 23, 1991, aged 93.

Charlotte Roberts, Tuberculosis: The Disease of Poverty, [6]

References and Further Reading:

- [1] Florence Seibert, American scientist, at Britannica Online

- [2] “Florence B. Seibert.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. Encyclopedia.com. 5 Oct. 2017

- [3] Robert Koch and Tuberculosis, SciHi Blog, Dec 11, 2013.

- [4] Florence Seibert, American Biochemist, at Chemistry Explained

- [5] Florence B. Seibert on Wikidata

- [6] Charlotte Roberts, Tuberculosis: The Disease of Poverty, 2015, Gresham College @ youtube

- [7] Lambert, Bruce (1991-08-31). “Dr. Florence B. Seibert, Inventor Of Standard TB Test, Dies at 93”. The New York Times.

- [8] “Florence Seibert, American Biochemist, 1897–1991”. Chemistry Explained.

- [9] Timeline for Florence Seibert, via Wikidata